Mental health services ‘not safe’

A public inquiry into the deaths of mental health inpatients in Essex has highlighted repeated failings and hopes to effect change across the country. Ben Ireland heard evidence from the latest round of hearings

‘People say, “we will admit you to the ward because it’s safe”. That’s not true. It should be, “we will admit you to the ward because it’s necessary and we will make it as safe as possible”. But it is not a safe location to admit someone to.’

Consultant psychiatrist Ian Davidson explained how admission under the Mental Health Act is ‘not a neutral act’, and that – if taking away that person’s liberty is required – mental health providers must seek ‘the maximum therapeutic benefit’ from the admission.

Evidence heard at the latest round of hearings in the Lampard Inquiry, which is investigating deaths of mental health inpatients in Essex between 2000 and 2023, heard how the principles of therapeutic care and treatment are not being adhered to.

Those giving evidence said the lack of therapeutic intervention is not an issue confined to Essex but a result of systemic failings across country showing ‘the NHS at its worst’.

In his opening remarks, counsel to the inquiry Nicholas Griffin KC said the hearings would ‘seek out the truth’. ‘Wherever possible my ambition is to make lasting positive interventions to improve mental healthcare across the country’, he said, calling for not only ‘appropriate therapeutic care’ to be the norm but also ‘treatment with empathy and respect’.

As expert witnesses attested, and families have long complained, the ability to deliver empathetic and respectful care had been severely hampered by the growing pressures on mental health services, with staff shortages leading to burnout and ‘compassion fatigue’, greater use of restraint, and a higher threshold for access.

The inquiry highlights some of the issues raised in The Doctor’s series of investigations into the state of mental healthcare, Paucity of Esteem, where it analysed the rise in detentions under the Mental Health Act, the growing use of OOA (out-of-area) placements and a lack of access to services until patients are in absolute crisis.

Fragmented services

Giving evidence at the public inquiry, Dr Davidson, a former clinical lead for the Royal College of Psychiatrists who compiled a 2021 GIRFT report titled Mental Health – Adult Crisis and Acute Care, explained how systemic changes in the early 2000s led to a ‘fragmented’ approach to mental healthcare, causing delays, miscommunications and ‘barriers’ to care.

This, he said, left core community and adult mental health services having to absorb increased demand while staff and resources were put into new, specialist services that – because of the fragmented approach – were able to refuse referrals, leaving sick patients with no support as their conditions escalated.

Many patients were sent out of area, he added, which is ‘less safe’ because OOA teams do not have the same background knowledge of patients, compromising vital continuity of care.

Pressure to reduce inappropriate OOA placements led to a ‘culture of last resort’ where patients reached a stage of crisis before they were seen, having often been denied earlier interventions at the ‘optimal time’ to deliver therapeutic care.

‘Few people, even with SMI [severe mental illness], benefit from inpatient treatment,’ said Dr Davidson. ‘All conditions can be treated at home if we get them early enough.’

He said fragmented services, combined with a ‘controversial’ fear of labelling patients with diagnoses led to a lack of clarity for clinicians and patients being passed around services until they reach crisis point.

Co-occurring conditions left patients and families ‘frustrated’ when told they can’t be seen for one disorder until they’ve been treated for another, with the other service saying the same in return.

Over time, amid growing pressures, crisis ‘inadvertently’ became the metric by which patients were given access to treatment, which Dr Davidson said was almost always ‘too late’.

‘Defensive practice’

While inpatient services can be ‘necessary’ for some, Dr Davidson said waiting until people were in crisis to treat them could cause ‘prolonged trauma’ and lead to longer recovery times.

Growing demand and increased acuity also had the knock-on effect of early discharge of patients who weren’t yet ready to return to the community to make room for new patients being admitted.

Resulting poor outcomes led to a ‘blame’ culture, and staff fearing that ‘whatever we do we are going to get it wrong’, creating a tendency towards ‘defensive practice’ and a focus on form-filling to explain decisions, taking time away from delivering therapeutic care.

Attempting to ‘eliminate’ risks, such as self-harm and suicide, is ‘impossible’, added Dr Davidson, who said treatment should be delivered in the safest possible way to offer effective care. An ‘over-emphasis’ on form-filling, he explained, can give ‘an illusion’ of managing risk when in fact spending too much time on forms, at the detriment of therapeutic care, can make situations less safe.

‘If you have 15 minutes to assess someone and come up with a plan you can’t be going through hundreds of forms,’ said Dr Davidson, explaining how one of the core principles of psychiatry is to treat patients in the least restrictive way possible.

Staff shortages

Maria Nelligan, a former chief nurse and quality officer in the north west of England, told the inquiry how the latest data, for 2023, shows more than 13,000 mental health nursing vacancies in England.

A shortage of registered nurses means planned care, such as leave and therapeutic interventions, might be delayed, causing frustration for patients and having a ‘massive effect’ on their recovery.

A reliance on temporary staff with less time to build relationships with patients means less therapeutic care, creating a ‘vicious cycle’ where more staff want to leave, said Ms Nelligan. Because of the immense pressure, senior nurses depart, meaning more complex care falls on to more recently trained nurses still ‘finding their feet’.

A lack of nurses also means greater reliance on HCWS (healthcare support workers), who are not trained to the same level, cannot write care plans or give medication, ‘so we can’t expect the same interventions and outcomes’.

The inquiry heard how increased pressures on staff can mean greater use of restraint. And while all staff, including HCSWs, are mandated to be trained in restraint, it is ‘very intense’ and relies on there being enough staff present to be safe.

Ms Nelligan explained how use of restraint should always be recorded, but the inquiry heard that this was unlikely to be the case given the level of data against the experiences described by staff, patients and their families.

Dr Davidson said higher levels of locum, bank and agency workers ‘indicates that something is amiss’.

He explained how increased pressures lead to higher levels of burnout and ‘compassion fatigue’, which means higher staff sickness rates.

That then leads to a greater reliance on temporary staff, with greater responsibility on their shoulders. The result is reduced continuity of care, which contributes to the environment that causes burnout and compassion fatigue in the first place.

‘Chaotic’ footage

The public inquiry is focused on Essex because it was there where a group of families of those who have died while in the care of mental health inpatient services raised concerns, including waiving their right to anonymity to tell their loved ones’ stories.

Harrowing footage from a Channel 4 Dispatches documentary, Hospitals Undercover, are they safe?, was shown at the inquiry.

Hidden camera footage revealed how, in one instance, it took one minute and 53 seconds to cut a ligature, which should be done in 10 seconds, in a scene described by an expert as ‘chaotic’.

Another section showed what an expert said was ‘unnecessary use of force and restraint’ and a former patient described the lack of care as amounting to ‘torture’.

In one incident caught on a hidden camera, staff joked about fast-food diets while restraining a patient with an eating disorder who was hyperventilating and screaming ‘you are making me worse’.

Undercover reporting exposed staff members sleeping on wards when they were supposed to be monitoring patients one-to-one. This was backed up in a 2023 CQC report.

The documentary also heard from the mother of a patient who died after absconding. She said ‘lessons are not learned’.

Missing data

Evidence presented at the inquiry showed how information given by mental healthcare providers in Essex was ‘substantially incomplete’. Mr Griffin said the inquiry has ‘concerns’ about the reasons given for not disclosing full sets of data and was ‘unimpressed’ by the number of requests for extensions and late disclosures.

The lack of complete data means the inquiry cannot accurately say how many deaths fall within its scope, and ‘cannot draw any clear conclusions’ from the current information.

The inquiry requested disclosures from EPUT (Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust), formed after the merger of NEPT (North Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust) and SEPT (South Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust), as well as private providers Priory, Signet and St Andrews.

Stephen Snowden KC, speaking on behalf of patients and bereaved families, said ‘obvious gaps’ in the data displayed either a ‘lack of compliance’ or ‘selective’ use of information.

Brenda Campbell KC, on behalf of the bereaved families, said data keeping was a ‘fundamental aspect’ of patient safety and the ‘paucity’ of data in Essex was ‘no surprise’ to families who had ‘already hit that buffer’.

Routine gaps in data from providers that have been ‘repeatedly told’ of the importance of data keeping were akin to a ‘cover-up’, she argued, saying it ‘hides failures’ and prevents learnings while ‘family after family, and coroner after coroner hear the same platitudes’.

That ‘no attempt’ had yet been made to analyse and categorise the data despite the high level of deaths in inpatient settings in Essex demonstrated ‘no desire to learn lessons’, she said.

Questioning the reliability of available data, she noted how some families reported inaccurate records or ‘manipulation’ of records.

‘Extraordinary and shocking’

Counsel to the inquiry noted how despite the ‘significant number’ of deaths within the scope of the inquiry, and the likelihood of those resulting in inquests, EPUT had only provided copies of 32 PFD (prevention of future death) reports from coroners and does not hold a central record.

The inquiry is pushing for more data and said ‘not enough is being done’ to monitor PFD reports.

EPUT reviewed 70 narrative conclusions given by coroners, of which 39 included adverse findings against the trust and/or its staff.

In 21 records of inquest relating to the trust where no PFD was issued, seven included a rider of ‘neglect’ – all of which involved inadequate risk assessment and lapses in care planning while failures in monitoring and observation protocols arose in three. There was also a finding of neglect in one record of inquest relating to a death at private provider St Andrews.

Ms Campbell said the number of deaths in Essex mental health inpatient units was ‘extraordinary and shocking’, and that ‘too many of those deaths arose from the same systemic failings’.

‘Appalling’ delays to inquests, which should be completed within six months but often take much longer, are ‘incredibly distressing’ for families, she added, pointing to a lack of legal aid or a satisfactory appeals process.

Families can feel ‘impotent’ when faced with ‘institutional defensiveness’, providers failing to provide evidence or delaying and failing to disclose information.

She said providers have given ‘shameful misrepresentations’ that lessons have been learned ‘when they have not’, causing families ‘re-traumatisation’ and creating a ‘barrier to change’.

Addressing PFDs, she said EPUT’s statements had been ‘replete with attempted justifications and excuses’ and their use of language ‘obstructs the discharge of their vital PFD responsibilities’. The failure to keep central records, she added, was ‘worrying’.

‘Systemic issues’

A HSIB (Health Services Safety Investigations Body) report published in January found ‘a number of significant systemic and cultural issues’ across mental health inpatient services nationally, making 17 safety recommendations and 23 safety observations.

The HSE (Health and Safety Executive) has brought two prosecutions in Essex.

In 2021, EPUT was fined £1.5m after being found to have failed to manage the environmental risks from fixed potential ligature points in its inpatient wards between October 2004 and March 2015. Eleven patients died after using ligature points to harm themselves, there were also ‘near misses’ and a 12th patient died shortly after the period in question.

In 2014, NEPT was fined £10,000 after an 18-year-old patient with a history of trying to abscond suffered serious injuries after falling from a first-floor window of a secure unit in Harlow.

The inquiry heard how 29 doctors working at mental health trusts in Essex have been referred to the GMC since 2006. No action has been taken, although some cases continue.

Some 133 nurses in Essex have been referred to the NMC since 2008, relating to 149 incidents. In 24 cases, their fitness to practise was found to be impaired, with six nurses struck off, 13 suspended, four cautioned and conditions on practice ordered on four. A further 24 cases remain open.

The HCPC (Health and Care Professions Council) has received 12 referrals in Essex since 2003; eight psychologists and four occupational therapists. Eleven cases have been closed, and one person was voluntarily removed from the register on health grounds.

Mr Griffin noted the ‘high threshold for taking action against individual healthcare professionals’ and that regulators were better suited to dealing with ‘low-level but widespread’ concerns where the CQC (Care Quality Commission) would investigate systemic issues.

In May 2023, the CQC downgraded EPUT’s rating to ‘inadequate’. It has since been moved to ‘requires improvement’. It issued NEPT with a warning in 2016 for not addressing concerns raised during a previous inspection, although no civil or criminal action was taken.

Patients ‘deserved better’

The PHSO (Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman) found ‘a series of significant failings’ in a 2019 report.

It looked at the care and treatment of two vulnerable young men who died shortly after being admitted as well as ‘wider systemic issues’ including ‘a failure over many years to develop the learning culture necessary to prevent similar mistakes from being repeated’.

‘Mr R,’ a 20-year-old with substance misuse and anger issues, was found unresponsive in his room a short time after asking to be discharged. The PHSO found ‘failings in the care and treatment provided’.

Sir Robert Behrens, the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman until March 2024, told the inquiry Mr R ‘deserved much better’ and criticised the ‘patronising’ approach from staff who had suggested he had wanted to be admitted so that he had somewhere to live.

Matthew Leahy, a 20-year-old diagnosed with delusional disorder caused by cannabis use, was found hanging in his room eight days after being admitted in 2012. The PHSO identified ‘significant failings’ in his care including 19 instances of maladministration, and that NEPT ‘had not taken sufficient and timely action to put things right’, which ‘added to the distress and frustration’ for his family.

Sir Robert described the report’s findings as ‘the National Health Service at its worst’, and a ‘near complete failure of leadership at the trust’.

He said the ombudsman had been ‘constrained’ by only being able to investigate when complaints were made. Uncovering issues in Essex relied on the families being ‘brave enough’ to complain, he said, and that resolution could have been ‘sped up dramatically’ if the ombudsman had been able to use its own initiative rather than being the ‘last resort’.

Pressure on staff

In 2023, the PHSO published a report which said ‘political leaders have created a confusing landscape of organisations, often in knee-jerk reaction to patient-safety crisis points’. It noted ‘significant overlap’ in regulators which ‘creates uncertainty about who is responsible for what’.

Sir Robert told the inquiry how, in two dozen cases, providers said there were no issues but the PHSO later found ‘serious failures’ and ‘avoidable deaths’ which was ‘very worrying’. He said the two main factors were limitations of PHSO powers and the complexity of processes for families.

The inquiry also heard the results of a PHSO survey into experiences of NHS mental healthcare in England. It found 20 per cent of patients did not feel safe, 56 per cent experienced delays, 42 per cent waited too long, 48 per cent were unlikely to complain and 32 per cent did not think their complaint would be taken seriously.

Sir Robert put a rise in complaints about mental health care down to ‘increasing pressure’ on the NHS in terms of staffing, finances, morale, and an over-reliance on temporary staff.

He described a ‘routine-isation’ of poor care and an endemic ‘lack of empathy’ from the time he became ombudsman in 2017. ‘When I met individual clinicians, it was clear they were working under very great stress,’ he said.

The PHSO found ‘shocking’ levels of record-keeping, including falsification of notes and documents that had ‘disappeared’. ‘Untruths were written down for the convenience and reputation of the body rather than accurately describing what happened to the patient,’ said Sir Robert.

He told the inquiry the issues raised in Essex are evident in other regions, and ‘the NHS needs to address [them] generally’. The difference in Essex, he said, is that ‘it happened again’ and ‘when there was clear warning’ from previous failures.

Sir Robert called for reform of the duty of candour, which he said ‘does not work’, and for better protections for whistleblowers who often ‘fear they will lose their jobs’ if they speak up about concerns.

Trust apologies

Consultant psychiatrist Milind Karale, executive medical director at EPUT, apologised to the families of mental health patients who had died while in care in Essex, for the ‘poor quality of care they received’.

He defended the trust’s approach to care planning and risk assessment, noting: ‘It’s the quality of the assessment that’s important’ and that risk assessments ‘cannot be a form-filling exercise.’

Dr Karale emphasised the importance of taking a holistic approach to mental healthcare, especially for patients with co-occurring conditions, saying: ‘The important thing is to provide an intervention-based treatment.’

Pressed on the number of rejected referrals, and how it makes some patients feel like they are being ignored, he said: ‘There has to be some way to manage these referrals.’

He said decisions to accept or reject referrals were made on a clinical basis but noted that trusts ‘don’t have the resources’ to accept every referral.

Asked whether some referrals were not accepted ‘to stop services becoming over-stretched’, he said ‘it’s a difficult question to answer’, adding: ‘It shouldn’t happen.’

In a similar vein, when asked if screenings were influenced by targets, such as waiting times, he said ‘they shouldn’t’ adding that if a referral is rejected it ‘should’ be passed back to the referring team or more information requested from the referring GP.

Including families at the referral stage can be ‘difficult’, he said, noting how some patients might want to limit their family’s involvement.

The inquiry heard how, before the introduction of an urgent care pathway for mental health patients in Essex, those presenting in crisis outside of core working hours were referred to emergency departments or reliant on NHS 111 services.

‘Unique challenges’

A position statement issued by EPUT offered the trust’s ‘deepest condolences to all those who have lost loved ones while under the care of Essex mental health services over the past 24 years’ and said services are ‘evolving for the better’.

The statement, signed by trust chief executive Paul Scott, said it is ‘important to acknowledge the wider issues facing mental health across the sector’, its ‘unique challenges’ such as increased demand, and high levels of neurodiversity among patients, as well as the impact of COVID.

He said EPUT has tried to assist the inquiry ‘to the best of our ability’ by providing the relevant information and documents it holds, and ‘will do our best’ to provide data from before the formation of EPUT, formed through a merger which aimed ‘to improve standards of care and outcomes for patients’.

He said ‘much has been achieved’ in improving care since EPUTs creation in 2017, but also that ‘much remains to be done’.

Noting the ‘complex’ commissioning structure of mental health services, along with funding restraints, he noted the ‘opportunities for simplification’ which ‘could have significant patient benefits’.

‘The process of change is a lengthy and ongoing process,’ he said, noting a lot of improvements made via efforts to learn from the past are ‘relatively new, and will take time to make a real and practical difference’.

‘We have seen improved outcomes as a result of the changes we have made. But I know there is more to do.’

‘Not an outlier’

In his closing statement, counsel to the inquiry Mr Griffin said there are ‘early indications are that Essex is not an outlier’ and ‘some of what was occurring may reflect the national picture’.

Mr Griffin noted that some of the data responses given by EPUT were ‘very limited’ and documents provided were ‘somewhat haphazard’, raising questions about the trust’s record keeping.

He concluded by saying: ‘We will continue to work to uncover the truth, expose wrongdoing, and to allow us to establish facts and make recommendations for real and lasting change.’

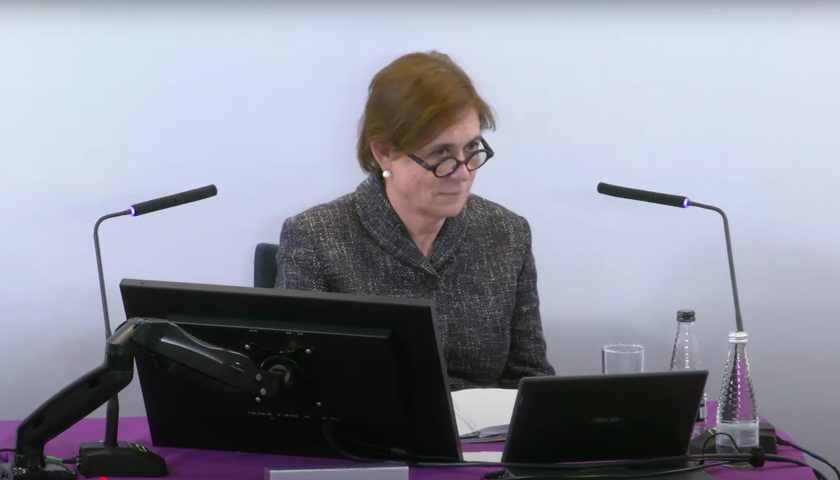

The Lampard Inquiry, chaired by Baroness Kate Lampard, is the first ever public inquiry into mental health services in England.

Public hearings began in September 2024, and individual cases are to be heard in July 2025. The inquiry is not a criminal proceeding, but its presence would not prevent misconduct allegations being brought against organisations if deemed necessary.

(Image credits: Getty and Lampard Inquiry)