'Incredibly alarming' – Trump's USA steps away from global health role

'Incredibly alarming' – Trump's USA steps away from global health role

The US president's decision to leave the World Health Organization has left doctors deeply concerned about the future of its vital work across the world. Tim Tonkin reports

‘It was the greatest achievement to be part of that. I was so proud of being part of that fight to end smallpox.’

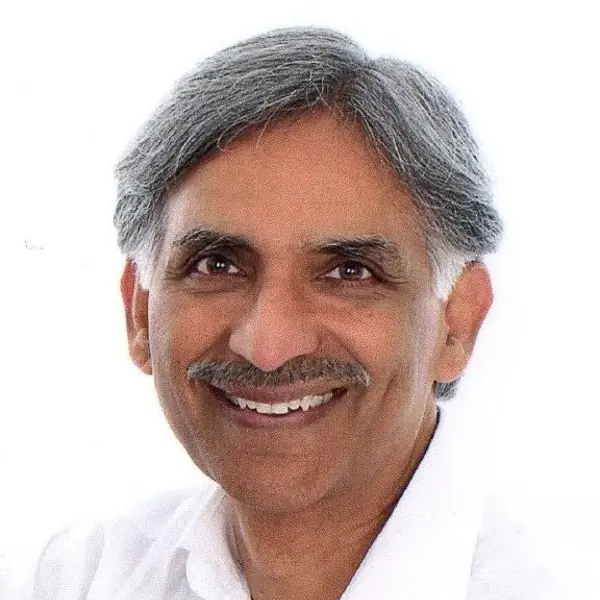

As a young doctor in early 1970s Radhamanohar Macherla volunteered his services in the state of Bihar in eastern India, where efforts were under way to eradicate a disease, which, until just 45 years ago, had ravaged humankind for centuries.

More than 50 years on, the now-retired consultant physician feels immense pride for the part he played in a huge global effort, which saw nations working together to identify and isolate outbreaks of the disease and deliver vaccinations to millions of people.

‘We were based at the headquarters of a district and as soon as we got notification of a suspected case, we used to drive out there no matter what time of day,’ reflects Dr Macherla.

‘We used to travel across the river Ganges, which during the monsoon season was quite difficult because all the riverbanks were breaking down and flooding. Once we arrived at the affected village, we had to vaccinate everyone within 48 hours.’

The 13-year campaign, which was orchestrated and overseen by the WHO (World Health Organization), is thought to have cost around US$300m, with around a third of this funding coming from the USA.

While the USA remains to this day the single-largest financial contributor nation to the WHO, this status may be set to change soon following an executive order issued on 20 January by US president Donald Trump.

The order, the second of its kind to be put forward by Trump as president, calls for the withdrawal of the USA from the WHO citing the organisation’s ‘mishandling’ of the COVID-19 pandemic and what it describes as the ‘unfairly onerous payments’ to the WHO by the USA.

'Collective spirit'

For Dr Macherla, who worked closely alongside US epidemiologist David Pratt during his time in Bihar, the announcement the USA will no longer play a role within the WHO is one that fills him with regret and concern.

He says that, while ending smallpox remains one of the WHO’s crowning achievements, the organisation’s efforts have brought the world to the brink of being free from Polio, adding that its leadership was also vital in helping to contain the Ebola virus outbreak of 2014.

‘I felt so sad about it,’ he explains to The Doctor.

‘I used to love working for WHO because I found myself working alongside those from places like America, Germany and from the UK as well.

‘It gave me a collective kind of ideology and made me to never think about the difficulties. I remember in India when our jeep was stuck deep in the mud at 10 o'clock at night in the middle of nowhere and that collective spirit gave me the strength to go on.

‘I’m very passionate about the WHO; what it does and stands for. The [COVID-19] pandemic has shown us that, just like for a wildfire, there are no boundaries and disease does not discriminate. Ultimately, what matters is how effective the countries’ collective efforts to tackle global health crises are.

Exiting the WHO is not something which can happen in the short term, with president Trump’s order subject to congressional approval and the USA legally required to meet its existing financial obligations and provide a one-year notice for its intention to leave.

I'm very passionate about the WHO; what it does and stands for

Radhamanohar Macherla

Certain aspects of the order, however, such as the requirement to ‘recall and reassign United States government personnel or contractors working in any capacity with the WHO’, appear to have already been implemented as of 27 January.

Should the USA withdraw, however, the WHO would be losing a member nation which provided just under US$1bn in funding during 2024/25, along with access to the USA’s significant medical and scientific expertise.

Indeed, the WHO specifically cites the support of the USA in addressing health emergencies including the 2024 mpox epidemic in central Africa, and an outbreak of Marburg virus in Rwanda through ‘surveillance, contact tracing, and public health communication’.

‘The USA and WHO share a long-standing partnership, delivering life-saving humanitarian assistance to communities devastated by conflict, natural disasters and disease outbreaks,’ the organisation states on its website.

‘By supporting WHO’s emergency health efforts, the USA drives global health security, from preventing and preparing for future threats to delivering rapid response and recovery when it matters most.’

It is a situation professor of global public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Mishal Khan believes poses risks but also potential opportunities for the WHO and how it operates.

‘I think a strong WHO is really important, really beneficial to the world,’ says Professor Khan.

‘During COVID and other huge humanitarian crises it has played a really important role in being evidence-based and a neutral voice.’

While a formal withdrawal from the WHO is yet to come to pass, statements and actions by the Trump administration relating to global-health initiatives have already had an unsettling effect on delivery of care.

On the same day the executive order on the WHO was issued, the US government also implemented a 90-day pause on its foreign-assistance spending, funding for which includes the activities of PEPFAR (The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief).

Founded in 2003, PEPFAR provides access to HIV prevention, treatment and care and is credited as having helped to save more than 26 million lives worldwide.

Vital work at threat

While subsequent announcements by US government departments made on 28 January and 1 February sought to exempt PEPFAR from the spending pause, confusion with the future delivery of this initiative remains.

Prof Khan believes the WHO will have to prepare for the possibility it will no longer be able to depend on the significant financial and logistical support of the USA.

She adds, however, that this could encourage other member nations to play a larger role in the organisation and thus promote a more sustainable approach to funding going forward.

‘There has already been an impact [from the announcement] in terms of the core business that health teams would be doing because of the uncertainty caused [around finances], even if there isn’t an immediate impact on funding, [it] causes a lot of distraction,’ says Prof Khan.

‘I think in the immediate term the overall pot of money is likely to shrink. Longer term, however, this might create an opportunity for other countries to step in to meet that shortfall and open up space for a more level playing field for institutions from low- and middle-income countries to play a bigger role in the WHO.

‘I think that that's where some of the uncertainty lies in terms of which countries step in and what interests they bring. We often don’t reflect enough on the fact that [wealthy] countries such as the USA give to the WHO [which is] tied to a lot of influence.’

In the wake of the executive order, the WHO has expressed its regret emphasising its hope that the USA will ‘reconsider’ its intention to withdraw, adding the organisation wishes to continue a ‘constructive dialogue’ to benefit ‘the health and well-being of millions of people around the globe’.

BMA international committee chair Kitty Mohan says the association is deeply concerned about the potential global-health implications which might result from a defunding of the WHO’s activities.

Dr Mohan says the BMA has since written to prime minister Keir Starmer urging the UK to increase its voluntary contributions to the WHO by 5 per cent in the next three years.

She says: ‘It is incredibly alarming that the USA may defund more than US$1.2bn from WHO’s budget, and that this may threaten the WHO’s essential work, such as the WHO programmes to eradicate polio and tuberculosis and the coordination of HIV and AIDS prevention work in Africa.

‘The WHO programme for 2025-28 sets an ambitious global-health agenda which demands significant political and financial resources and commitment for its successful implementation and will need funding of US$7.1bn for 2025-28 through voluntary contributions, to tackle global health and development challenges.

‘The BMA has previously written to the prime minister to ask for the UK to increase UK voluntary contributions to the WHO to US$450m over the period of 2025-28, which would represent a nominal increase of 5 per cent.’

(Picture credit main image: World Health Organization)