Jobless GPs – just when they’re needed most

General practice is under intense pressure and yet many locum GPs are unable to find enough work. They tell Ben Ireland that the funding crisis and perverse incentives to hire anyone but GPs must be urgently resolved

In GP-land, there is something of an absurd paradox taking place.

On the one hand, patients complain about a lack of access to family doctors. At the same time, there is an army of GPs desperate for work, but practices are unable to hire them.

This ‘ridiculous situation’, as BMA GPs committee chair Katie Bramall-Stainer describes it, comes from practices – already starved of cash after huge real-terms cuts to their funding – being incentivised to hire anyone for their multidisciplinary teams except for GPs.

The knock-on effect? A staggering 84 per cent of locum GPs, according to a recent BMA survey, are struggling to find enough suitable work. Locums are now working an average of three sessions a week, down from 5.8 in 2022, a difference of a full additional day a week per person.

Some 91 per cent of respondents said availability of locum GP roles had decreased and 84 per cent said suitability had reduced where jobs were available, and 83 per cent of those who can find work did not feel they had enough time in sessions to provide patients with safe and thorough care. Nearly a third (31 per cent) reported having to work beyond their agreed session contracts to meet these standards.

The number has reduced, and the competition has increased

Dr Goyal

The Royal College of GPs conducted a similar survey in June, which provided similar findings. Of its respondents, 61 per cent who had looked for an NHS GP role in the past year found it ‘difficult’ to find an appropriate vacancy, rising to 72 per cent among GPs in training.

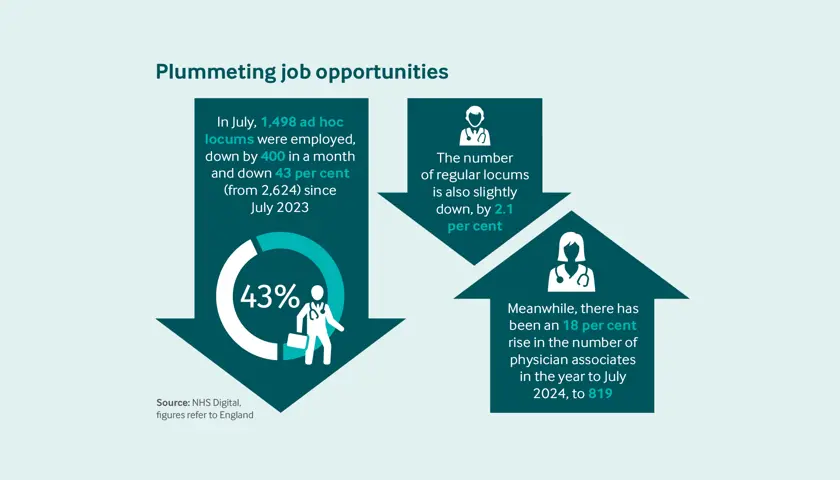

NHS Digital data shows a drop in the number of locum GPs employed across England. In July, 1,498 ad-hoc locums (those employed for short periods in a practice, perhaps a single session) were employed, down by 400 in a month and down 43 per cent (from 2,624) since July 2023. However, the number employed in July 2024 is likely to rise due to a reporting lag.

The number of regular locums is also slightly down, by 2.1 per cent. Meanwhile, there has been an 18 per cent rise in the number of physician associates in the year to July 2024, to 819.

West Midlands locum GP Aaliya Goyal (pictured above) told The Doctor how the number of sessions offered – via purpose-built apps, WhatsApp groups and direct contacts with practices – have dried up, from a combination of fewer sessions offered and more doctors competing for them.

Dr Goyal explains how, on one leading app, it is typical for as many as 25 locum GPs to register interest in a single session when it used to be more like one or two – and how job offers on WhatsApp are ‘pounced’ upon almost immediately.

‘The number has reduced, and the competition has increased,’ she says. ‘You have to be glued to your phone 24/7 [to secure a session] because there will always be someone who will reply within minutes.’

This competition-based GP market has resulted in lower rates of pay for locums, who have additional outgoings compared with salaried GPs such as indemnity costs and their own study leave. This has resulted in a significant loss of earnings amid a cost-of-living crisis.

‘You hear stories of doctors becoming Uber drivers to make up the difference,’ says Dr Goyal. ‘If it wasn’t for my specialist interest in occupational health, I would have really struggled. That has kept me afloat. Lots of GPs with specialist interests are in the same position.’

Dr Goyal resigned from a salaried role because the employing practice would not accommodate her request for a reduction in hours based on her personal circumstances. Other GPs make the choice for reasons such as combating burnout, health issues, caring responsibilities and seeking work/life flexibility.

Dr Goyal accepts that locum GPs should expect that a level of ‘entrepreneurship’ is required, and that by their nature as expert generalists GPs typically ‘thrive in chaos’ but says the current landscape has created a fastest-fingers-first mentality.

You hear stories of doctors becoming Uber drivers to make

up the difference

Dr Goyal

The situation, as it stands, has led many doctors to seek alternate work, with the risk that once they leave the profession they may not return. Some 33 per cent of survey respondents told the BMA they had already made definite plans to change career paths, with 31 per cent of those saying the lack of suitable shifts was forcing them to leave the NHS entirely.

The result? The number of GPs per patient continues to be stretched. NHS data released in August shows a record average of 10,113 registered patients per practice. Each full-time equivalent GP is now responsible for an average of 2,293 patients, an increase of 355 patients per GP, or 18 per cent, since 2015.

Dr Goyal notes how GPs who struggle to obtain locum sessions, and as a result don’t complete enough sessions a year, could lose their place on the national performers list, which is required to work as a GP.

‘I’ve had conversations with GP trainers who have put their heart and soul into training doctors to become GPs but see them leaving once qualified because there isn’t enough work,’ she adds. ‘Locum GPs are an undervalued and underutilised section of the workforce who have been neglected. If this continues, more and more will start drifting away.’

Dr Goyal has considered returning to a salaried role, for extra job security, but says the opportunities available come with too great a supervision responsibility – with some practices asking salaried GPs to supervise multiple members of the team such as GP registrars, nurses and ‘additional’ roles such as physician associates.

‘That is a level of risk I’m not prepared to take,’ she says. ‘Even if it’s the right setting, the right number of sessions and the right pay. I don’t feel comfortable taking responsibility for the interpretation of patient presentations by multiple members of the team in the same session time even if others may be happy to.’

One of the reasons given for the crunch in locum roles, in England, is ARRS (additional roles reimbursement scheme). Introduced in 2019, ARRS allows PCNs (primary care networks) to claim reimbursement for the salaries (and some costs) of 17 roles within the multidisciplinary team.

Life or death

Clare Bannon, a GP partner and the BMA’s GPs committee England lead for clinical and interface policy, says the ring-fencing of those funds has essentially ‘blocked us from employing GPs’.

Dr Bannon explains that, as expert generalists, GPs are able to differentiate between routine conditions and serious illnesses where non-GPs are not. So, reducing access to GPs is ‘potentially a matter of life and death’.

Royal College of GPs chair Professor Kamila Hawthorne agrees. She says: ‘Schemes like this are now proving counter-productive and leaving GPs without jobs and, in some cases forcing them to leave the profession altogether or look for opportunities overseas.

The opportunities for GPs entering the NHS workforce are fewer and fewer

Dr Steggles

‘Members of the wider practice team are valuable and can help to expand the services available to patients, but they aren’t substitutes for the key specialist skills and expertise GPs provide and they can’t be used to plug gaps in the GP workforce.’

The new Labour Government sought to relieve this pressure by ‘removing red tape’ and allowing newly qualified GPs to be hired through ARRS money by the end of this year. Health secretary Wes Streeting said this would mean 1,000 more GPs could be recruited.

But this does not appease either existing and experienced locum GPs seeking work, or the practices that want to hire them. Even GP registrars who are due to take advantage of the change as they qualify as GPs are not satisfied – for the good of their patients and their careers.

Because funding is allocated at PCN, not practice level, some newly qualified GPs may even be forced to move across the country at short notice, uprooting their families. And the BMA is pushing for more clarity on pay, job plans and mentoring for newly qualified GPs hired through ARRS. Many, before and since the update, are being targeted by overseas recruiters.

Malinga Ratwatte, chair of the BMA’s GP registrars committee, says: ‘Newly qualified GPs want to develop long-term relationships with their patients in order to provide continuity of care, leading to better outcomes for patients and better job satisfaction for doctors.

‘Newly qualified GPs need to be part of a practice team to get the mentorship needed for fully independent practice. While this [amendment to the scheme] will alleviate short-term unemployment concerns, we still need a long-term solution for general practice.’

That long-term solution, he suggests, should be to provide adequate funding for GPs at practice level, rather than via PCNs.

It is a view endorsed by the RCGP and the BMA GPs committee for England, which is taking collective action over the ‘underfunded and overstretched GMS contract’. The BMA calculates that core funding to the GP contract in England (general medical services) has fallen by £659m (or 6.6 per cent) in real terms since 2018/19. An 11 per cent uplift in funding would be required to restore funding to 2018/19 levels.

Financial restraints

Mark Steggles, chair of the BMA’s sessional GPs committee, says: ‘Practices’ costs are going up, and funding isn’t keeping up. So, they’re having to look at how they can make savings to keep their doors open, making really tough financial decisions. Some would love to have more locums on board, but that’s becoming less possible.’

He says the disincentives to employ GPs, combined with the erosion of funding, has led to a decrease in the number of GP partnership opportunities and salaried roles – which means those who do end up with jobs face an even higher risk of burnout.

Dr Steggles became a locum GP after four and a half years in a salaried role owing to ‘escalating workloads’, and ‘so I could continue to do what I did, rather than leave [the profession] altogether’.

He says: ‘The opportunities for GPs entering the NHS workforce are fewer and fewer. GPs can’t find salaried roles, the ones that exist are less manageable and there’s a real lack of funding to employ locum GPs.’

With some 58,000 doctors on the GMC’s GPs register in England, and about 38,500 GPs working for the NHS in England, Dr Steggles points out that about a third are not working.

He said that while the new Government has made some ‘encouraging’ noises around its promise to ‘bring back the family doctor’, which offer ‘hope’, he stresses: ‘We need to see actions’.

There are talented GPs ready and able to work but practices can’t afford to hire them

Dr Bramall-Stainer

‘Patients want to be seeing GPs, and the GPs who are working are overwhelmed, having to supervise more staff as well as doing their

own regular clinics. We need to take the pressure off GPs who are in practices already, and make sure the fully qualified GPs looking for work in the NHS have opportunities.

‘In the current situation, many GPs don’t have much choice [than to become a locum]. You’re almost becoming a locum by default. All GPs are working beyond what is safe, and with increased competition, locums are having to compromise on safe working to get the roles.

‘The situation is desperate for all GPs, but when you’re faced with unemployment and you have mortgages, bills and families to support, you make decisions based on that. People can see this is not sustainable, so many are choosing to leave.’

Diverting the £1.4bn ARRS funding to practices and opening it up to spending on experienced locums as well would be a welcome step, says Dr Steggles. But he would prefer to see practices’ core funding increased overall so they can make their own choices based on which roles they feel are required for their patients rather than being led by incentives.

His assessment: ‘General practice is on its knees and needs more investment.’

The BMA GPs committee for England has begun its dispute with Government, with GPs urged to ‘work-to-rule’ as part of collective action until an adequate contract is agreed.

All the while, practices face soaring energy costs, higher wages for other staff and are still catching up with prices following years of double-digit inflation.

Labour’s tweaks are ‘nowhere near enough to save general practice’, Dr Steggles and Dr Bramall-Stainer said after its announcement. They insist fixing the contract at its very roots by improving core funding is the only solution.

‘We need to see the core GP contract funding increased so that practices have full control over who they recruit, without the need to go via bolt-on schemes.

‘There are experienced and talented GPs, ready and able to work, but practices can’t afford to hire them.’