Putting patients first

Putting patients first

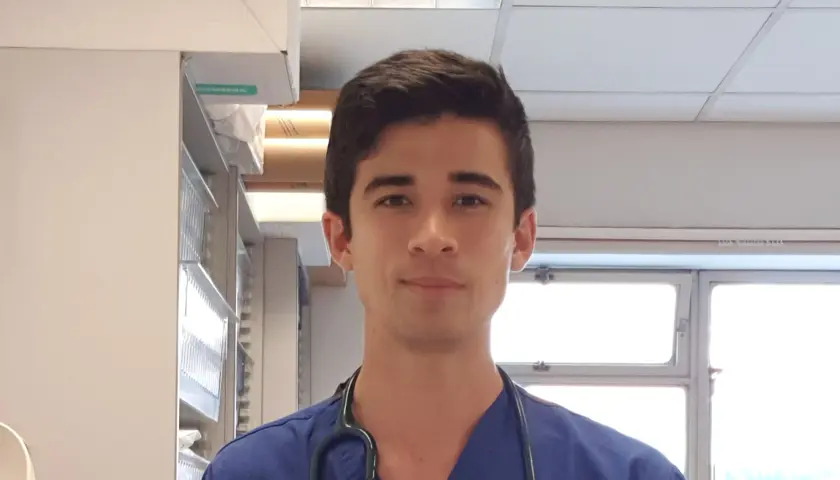

Kim Daybell was an elite athlete who abruptly gave up his sporting ambitions to work full-time as a doctor when the COVID pandemic struck. Five years on, he weighs up his choice with Seren Boyd

Kim Daybell was at the peak of his sporting career, fifth in the world in his class, and preparing for his third Paralympics – when medicine pulled rank.

Until then, he had managed to hold his medical training and table tennis in tension but, when the pandemic struck, he felt he had to choose between them. He decided to dedicate himself full-time to his work as a foundation year 2 doctor in north London.

‘I’d had a really great career in sport: I had played for 15 years, all over the world, and probably for the first time I thought my duty as a doctor should supersede my ambitions as an athlete,’ he says. ‘It just felt right.’

COVID allowed no time for the luxury of ‘what ifs’: he was seeing people die almost daily on the acute ward.

But the decision to put his Paralympic career on hold was to cost him automatic qualification for Tokyo 2020 and he retired two years later.

Five years on from that decision, has it all been worth it?

Rare condition

We meet at the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London, ahead of a meeting of Medics for Rare Disease.

The setting is somewhat surreal; we’re surrounded by anatomical and pathological specimens, human and animal remains. It is not lost on Dr Daybell that many rare conditions such as his are represented in the jars.

Dr Daybell has Poland syndrome, which caused him to be born with no pectoral muscles on his right side and no fingers on his right hand. A bilateral toe transplant at the age of two gave him opposing digits on that hand.

Sport was something his parents encouraged from an early age to build up his strength and confidence. He started playing table tennis with his dad in the family’s garage in Sheffield. By 11 he was in the national junior team. He made his international debut at 16.

The move into para sport was not inevitable, nor an instant decision – even when he was approached by ParalympicsGB in 2007. He would be assigned to class 10, the minimal disability classification.

‘I was a bit hesitant: I didn’t see myself in that sphere, having a relatively minor disability. But when I played my first event and saw what para-athletes were achieving, I was very quick to get involved.

‘Children with disabilities often lack confidence and have a lot of anxiety around having a disability; for me, Paralympic sport took all that away.’

The first year as a doctor is a really big adjustment and trying to do that alongside elite sport wasn't easy

Kim Daybell

However, it was tough. His training for his first Paralympics, London 2012, coincided with the early part of a medical degree at Leeds University. He was playing table tennis six hours a day around placements and study.

‘It meant a lot of organisation and knowing when to commit time to certain bits of your life – and I have a lot of people to thank for how I was able to manage that.’

He took a year out of medical school to prepare for Rio 2016 where he reached the quarter-finals in the men’s singles and team events. Then, he spread his foundation year 1 at Whittington Health NHS Trust across two years, working a 50 per cent rota alongside sports training in London and Sheffield.

‘It was tough and I found the work/training balance difficult,’ he says. ‘The first year as a doctor is a really big adjustment and trying to do that alongside elite sport wasn't easy. My team and the hospital made it possible and I'll always be grateful for that.’

In a 15-year sporting career, Dr Daybell won nearly 50 international medals including silver in the Commonwealth Games men’s singles and team silver at the European Championships.

'Walking a tightrope'

For years, then, medicine and sport competed for his time, even while complementing one another.

It was joining ParalympicsGB which made him choose a career in medicine. He recognised what medicine had done for him and his colleagues and it was medicine which enabled him to ‘give back’ when COVID took hold.

‘Sport is amazing but it's also very selfish. It's all about you being the very best athlete you can be,’ says Dr Daybell. ‘I’d been given a lot by medicine and by sport. People have given up a lot for me to get where I wanted to be.’

At some point, having to choose between his careers was probably unavoidable. He was already ‘walking a tightrope’ in trying to balance them: most of his Paralympian colleagues were full-time athletes.

Missing out on automatic qualification and a wild-card application for Tokyo was a blow, nonetheless. ‘That was a really hard time, really tough.’

When he retired in 2022, it was on his own terms. ‘Working through COVID, it had been nine months to a year when I didn’t really play and you probably need at least a year full-time to get back to where you were. Sometimes you have to know when to draw the line.’

He still plays recreationally and was declared National Champion in his category as recently as 2023.

‘For a year after retirement, I really struggled with filling my spare time. But it’s just a readjustment and didn't last too long. When you've competed at such a high level, nothing replicates that buzz and adrenaline.’

After compartmentalising medicine and sport for so long, Dr Daybell is allowing the two to merge now.

He is studying an MSc in sports and exercise medicine at University College, London, after completing his internal medicine training 2 and he is training as a classifier for Paralympic table tennis.

He is also starting to appreciate fully all that disability sport has taught him. Overcoming barriers – for patients and doctors with disabilities and rare conditions – has become something of a mission.

Dr Daybell is an ambassador for PIP-UK, the patient advocacy group for Poland syndrome, and for Medics for Rare Disease, a charity which specialises in rare-disease medical education and provides free training to healthcare professionals.

He received timely treatment as a child – but his involvement with the charities has taught him that many people with rare diseases have a long diagnostic journey and struggle to find continuing support and treatment.

‘Normally in medicine, common things are common but we doctors need to have it in mind that there might be something else going on. There’s a large body of people living with rare disease and it's important for us to educate ourselves.

‘As medics we can get tunnel vision about treating specific symptoms rather than treating the whole person. So, people with rare diseases often get bumped between different specialties. You don’t quite fit into any of the clinics. But one good contact with a doctor who knows what they're talking about can save a lot of clinical time and make a real difference.’

Patients will quite often ask me about my disability and I'll be open about the problems I've had

Kim Daybell

Dr Daybell is also keen to come alongside colleagues at work, supporting inclusion and staff disability networks. He knows the confidence and community that sport gave him are a privilege – although he has faced hurdles, too.

'I was interviewed for one medical school and they spent a lot of time talking about whether I would be physically able to be a doctor,’ he says. In fact, he can grip in both hands and hasn’t ‘come across much clinically that has been a problem’.

‘When I started new jobs, my approach was always to find my supervisor and say, “I don't think I'll need anything for this job but I might come to you for some support”. Everyone has been really supportive and lovely.

‘The problems come when those lines of communication break down. And I completely understand that some people wouldn't necessarily have that confidence to say they may need help.’

Dr Daybell has no regrets. Rather, he is proud of the way he has managed to balance sports and medicine and become a doctor as a disabled person. He is also grateful, often.

He loves his job, especially his interactions with patients. ‘Patients will quite often ask me about my disability and I'll be open about the problems I've had. Anyone in hospital, as I see it, is kind of temporarily disabled, so it helps build a bit of trust and connection.’

Medicine can be taxing, too – and having a life outside the day job has helped keep things in perspective. He recently took up marathon running.

‘I think lots of medics can get burnt out if they feel medicine is all-encompassing. I had something else that I did for a long time, another strand to my life.

‘When I look back now, I feel very grateful and lucky to have been able to combine two things that didn’t really feel would ever go together, for such a long time. But I still think I made the right choice.’

(Main image credit: ParalympicsGB)

- 28 February is Rare Disease Day

- Medics for Rare Disease is asking doctors to help drive rare disease awareness, by wearing stripey socks and uploading photos with the hashtag #ShowYourStripes @MedicsForRare

- For more info and digital resources, visit m4rd.org/rarediseaseday2025