On the receiving end: violence aimed at doctors

Doctors face the threat of violence every day, the risk fuelled by system pressures and patient expectations, which are not of their making

The patient was reclining on a trolley in a cubicle in the emergency department when Cathy Wield came to assess him.

She knew he had been agitated: security staff were in the cubicle. But he appeared calm when she approached. The flying kick to her chest was so hard it flung her against the wall.

Dr Wield immediately reported the assault to a senior colleague but no one checked how she was. She continued to tend to the patient for the next two hours.

‘I was in shock so I carried on working, and nobody suggested I shouldn’t,’ says Dr Wield, a Dorset-based specialty doctor in emergency medicine.

It was only at the end of Dr Wield’s shift that a manager asked if she was OK. By now, she was very sore and bruised. ‘They said, jokingly, “Do you want to join the six-hour wait to be seen?”’ She declined. She didn’t sleep that night.

Dr Wield logged an incident report and reported it to the police. But an assessment of the patient’s mental state meant no charges could be brought.

Unreported

Levels of aggression and abuse aimed at healthcare workers are hard to quantify.

In the latest NHS Staff Survey last November, more than a third of staff (35.4 per cent) who had frequent face-to-face contact with patients said they had experienced bullying, harassment or abuse from patients, their relatives or the public in the past year. Almost 15 per cent reported at least one incident of violence.

Nuffield Trust analysis found that levels of abuse and aggression reported in the 2015/2019 staff surveys remained fairly stable over that timeframe. Yet, much abuse goes unreported and national annual data on physical assaults has not been collected since 2017.

We all become desensitised over time in order to cope

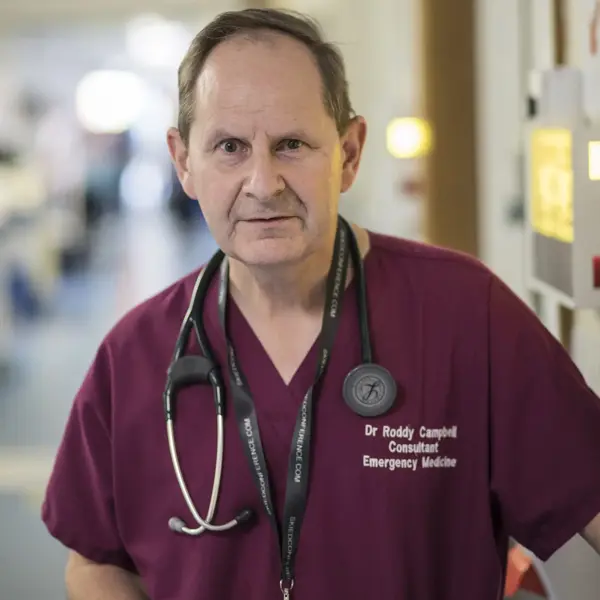

Dr Campbell

Anecdotally, doctors have reported a steep rise during the pandemic – and another spike in recent months.

In a survey by BMA Scotland in May 2021, almost nine in 10 GPs (87.7 per cent) in Scotland said they or their practice staff had suffered verbal or physical abuse in the past month.

The abuse has reached such a pitch that the Institute of General Practice Management has produced a video compilation of threats made to surgery staff, entitled ‘If I die It will be your fault’.

It recounts how one patient slashed the tyres of three staff members’ cars because, on phoning at 5pm, he was told he would have to wait till the next day for an appointment. Another turned up to the surgery with a hammer.

Political climate

Adam Janjua’s GP practice in Lancashire had to call the police recently to deal with a woman who had been declined a referral for a ‘cosmetic issue’.

She overturned a chair, thumped the desk, then screamed and swore for a full ‘15 minutes of chaos’, in the consulting room and waiting area, leaving only when she realised the police were coming.

Dr Janjua took to Facebook Live to ask patients to treat NHS staff with more respect – and to set the record straight over suggestions that GP surgeries have remained closed to patients during the pandemic. He believes the recent onslaught of passive aggression and abuse has been fuelled by tabloid headlines and health leaders.

‘It’s mainly people taking shots at us: “When are you going to start seeing patients? You’re just pocketing the money and not doing anything. Why don’t you help the hospital out?”

‘It’s very unfair because we never stopped doing face-to-face: we’re a training practice and we have lots of appointments. We get people blaming their medical problems on us, even if they’ve been referred. One child’s father threatened to come down and show us what he could do to us.’

NHS England’s letter in May telling GP practices to ‘ensure they are offering face-to-face appointments’ sparked what Dr Janjua calls ‘a full-blown forest fire’. Patients have ignored small-print provisos recognising ‘clinical reasons’ to refuse appointments in person, such as acute COVID symptoms.

‘Even patients who were on our side turned overnight,’ says Dr Janjua. ‘We’ve been firefighting ever since. Unless there’s an apology from NHS England on every newspaper’s front page, people won’t pay heed. They’ve damaged the reputation of the profession. The goodwill built up over the last year seems to have evaporated overnight.’

All part of the job?

As a consultant in emergency medicine, Roddy Campbell now expects to be in the firing line.

He’s sanguine about the fact that he experiences violence or aggression ‘every other shift’ these days.

Most of it is fuelled by drug and alcohol misuse or mental health issues; a small proportion is down to people with poor coping strategies.

Things have been bad for ‘two or three years’ in his emergency department in southwest England. It is frequently overcrowded, sometimes with twice or three times the number of patients it was designed for.

The hospital is near full occupancy, or over, most of the time. Staffing levels are inadequate for the level of demand.

‘We recently had a patient in the emergency department for several days, waiting for a suitable place to go,’ says Dr Campbell.

‘They abused and assaulted several staff members and caused huge disruption. It was very frightening for other patients and an overcrowded emergency department is a totally unsuitable environment for people with mental health conditions.

‘The worst part is knowing we’re not giving our patients the best care we can. We’re trying to manage the corporate risk and spread our care across a large number of patients without enough staff or space.’

Even patients who were on our side turned overnight

Dr Janjua

The recent reopening of hospitals to a backlog of medical concerns and pent-up frustration means patients have become even more agitated.

‘We were already on the verge of decompensating, but COVID has pushed us over the edge,’ says Dr Campbell.

Mavi Capanna (pictured below), a core trainee 2 general psychiatry doctor in London, says incidents in psychiatry are so common they’re seen as ‘normal’.

‘Patients assault staff and make significant, and at times scary, verbal threats to harm you, and this can become so normalised that for some staff it’s seen as part of the job,’ says Dr Capanna.

‘But when you go home, and talk to people who aren’t in your profession, you realise how wrong and damaging it is.’

Becoming immune

It’s clear something has to change, not least for team morale and staff retention.

Feeling part of a supportive, close-knit team is ‘the saving grace’ for Dr Campbell. But he worries he has become so inured to aggression he may fail to spot its effects on more junior staff.

‘If, like me, you’ve seen a lot of abuse and assault in your career, it’s harder to appreciate how awful it is for a brand-new junior doctor who has just seen something unpleasant, because we all become desensitised over time in order to cope,’ he says.

‘They might be feeling utterly deflated and vulnerable, and maybe blaming themselves for what’s happened, which is a sort of moral injury.’

The impact on patient care, too, makes a pressing case for change.

As both Dr Wield and Dr Campbell point out, any form of rudeness inhibits people’s ability to treat patients safely for a time – a point emphasised by the Civility Saves Lives campaign.

‘It absorbs your emotional bandwidth so you have a great deal less emotional energy for all the other things you’re supposed to be doing,’ says Dr Campbell.

Dr Wield worries that a secondary consequence is medical staff becoming hardened towards people behaving badly.

‘The risk is they value less people who behave like this,’ she says. ‘Unfortunately, a lot of these are people whose chances of dying young are much greater.’

Taking responsibility

Policy is hardening against aggression and abuse. The first NHS violence reduction strategy, launched in 2018, aims to ‘better protect staff and prosecute offenders more easily’.

A national Violence Prevention and Reduction Standard for NHS organisations was published in January.

The Government is looking at increasing the maximum sentence for assault on emergency workers, including doctors, from 12 months in prison to two years – something for which the BMA has lobbied hard.

June saw the start of a rollout of bodycams across 10 ambulance trusts in England to record, and thereby reduce, abuse.

The number of physical assaults on ambulance staff in England last year was ‘30% more than five years ago’, according to NHS England.

Patients assault staff and make significant, and at times scary, verbal threats to harm you

Dr Capanna

Since April 2020, it has been possible to deny treatment to patients who are abusive, as well as to those who are aggressive or violent, unless they need emergency care.

But ‘zero-tolerance’ will remain an empty slogan without effective sanctions.

Hospitals’ red card system – barring offenders for two years – is unenforceable, says Dr Campbell.

‘If somebody has taken a significant overdose or has a head injury that suggests they have a bleed on their brain, you really can’t enforce that,’ he says.

But people should be supported to take responsibility for their actions.

‘If you’re delirious with an encephalopathy, it’s not your fault if you’re badly behaved.

‘If you’re drunk and disappointed because you had a fight and you lost, and you don’t like waiting, then it probably is.’

Drawing that line can be hard, especially in psychiatry – but some fear the pendulum has swung too far.

‘I worry that we’re medicalising psychosocial problems and we are increasingly tolerant of bad behaviour,’ says Dr Wield. ‘If people aren’t held to account, it doesn’t help them to resolve issues.’

Culture shift

Doctors’ suggestions for tackling aggression and abuse are wide-ranging: more staff, more space, more security, more sanctions.

More ‘detox units’ providing medical checks for the intoxicated, to relieve pressure on emergency care. A national awareness day highlighting the problem.

Dr Wield has been trying to help improve support for staff experiencing abuse in her own trust.

‘There have been times when I’m not sure I want to do this anymore,’ she says. ‘That’s why I needed to speak up, make something positive happen as a result of my bad experiences.’

Dr Capanna, a member of the BMA’s North Thames junior doctors committee, says that there should be a national benchmark for safety standards. Poorly performing trusts need to be held accountable and supported to improve.

Shobhna Shah, a London-based anaesthetist and aviation medicine specialist, says even low-level workplace violence and abuse should not be tolerated.

She refers to criminology’s ‘broken window theory’ that links disorder and incivility within a community to subsequent serious crime.

We get people blaming their medical problems on us

Dr Janjua

Dr Shah believes there is a place for security systems with a deterrent effect, including trained security staff, CCTV, fixed alarms, personal alarms and communication systems. Employers need robust safety protocols and they must be enforced.

And, she says, staff at all levels need proper training in recognising warning signs, interpersonal skills and de-escalation techniques.

Dr Shah feels patients need support too, recognising their anxiety can be fuelled by issues such as lack of choice, lack of information and lack of space. Creating a calm environment where people are kept informed and noise is minimised is key.

But equally important is building non-acceptance of abuse among staff.

Less than half (48.4 per cent) of participants in the 2020 NHS Staff Survey said ‘they or a colleague reported harassment, bullying or abuse at work the last time they experienced it’.

Dr Shah understands why people don’t want to report.

‘People might not want to relive their experiences. But we must make sure incidents are reported so we know the true extent of the problem. Abuse and physical risk should not be an intrinsic part of the job of a health worker.’

- Until September 2024, resident doctors were referred to as ‘junior doctors’ by the BMA. Articles written prior to this date reflect the terminology then in use