Making exception reporting work

Making exception reporting work

Exception reporting, the system resident doctors in England use to report additional working hours, has been stymied by bureaucratic and cultural barriers. But after a breakthrough in negotiations between the BMA and the Government, it may at last work as intended. Ben Ireland reports

‘If you stay late, you should get paid – it’s that simple.’

This take, from core trainee 4 in anaesthetics Schnell D’Sa, doesn’t feel like a particularly controversial opinion – but she is pointing out one of the biggest grievances among resident doctors, who for a long time have not been paid for their additional hours worked, at least not without a huge battle.

Exception reporting, the process resident doctors use to record their working hours, identify unsafe staffing levels and protect patients, has been in place since the 2016 contract was imposed on resident (then junior) doctors in England.

Since then, it has become quite a bone of contention.

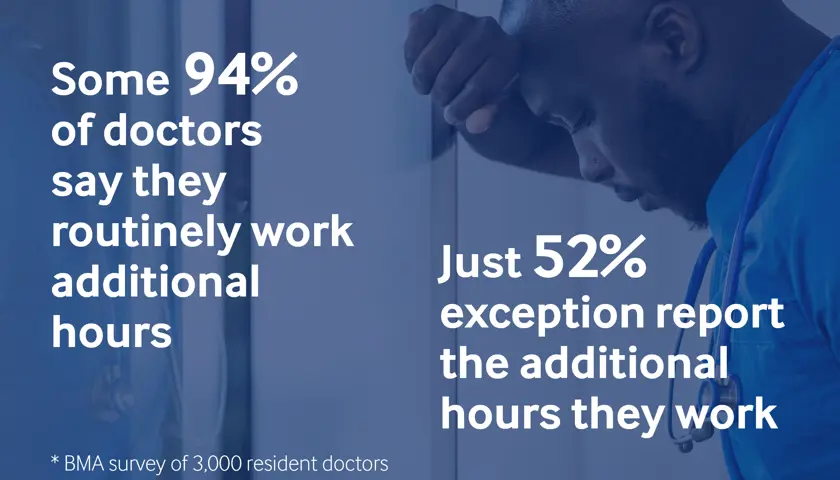

Responses to a BMA survey of 3,000 resident doctors, which concluded in 2024 – shared exclusively with The Doctor – lay bare the extent of the problem. Some 94 per cent of doctors report that they work additional hours each month but 52 per cent never exception report those additional hours.

Individual doctors responding to the survey said, ‘nothing happens when I exception report’, that ‘there is an acceptance that registrars don’t exception report’, or that ‘colleagues have experienced conflict with senior consultants when they exception reported’.

And it can be technically difficult too, often taking as long to complete an exception report as the additional time spent working. Survey respondents noted problems with logins, either that they never received details, that those details didn’t work, or that chasing logins could be a ‘nightmare’.

However, things are set to change and the process made a lot less onerous for the resident doctors seeking a fairer settlement from their employers and the busy consultants who, up to now, have been responsible for signing requests off.

Reform of exception reporting was agreed in the pay deal accepted by the BMA resident doctors committee in 2024 – and ‘intense negotiations’ as to what those reforms might entail have been under way for more than a year.

Last week, a breakthrough was made as the BMA resident doctors committee agreed a framework of reforms, which NHS hospitals must now implement by 4 February 2026.

Routinely staying late

Dr D’Sa returned from a spell working in Australia to start her specialty training in the East of England with a ‘whole new perspective’ on working additional hours.

She noticed during an acute medicine rotation how ‘a lot of my colleagues were routinely staying late, especially medical registrars’, owing to rota gaps, which added up to ‘multiple hours’ of unpaid work above their contracted employment each week.

‘It was ridiculous,’ says Dr D’Sa. ‘You know you’re not going to be getting paid but if you don’t stay your patient would suffer, and it would take more time to hand over than complete the job. It felt like consultants, or the senior management team, were unaware of how many additional hours resident doctors were doing.

‘In Australia, even if I worked a minute late, all I had to do was fill in a very simple form with our shift hours, hand it to the admin clerk and they would get it signed off – no questions asked. If you stayed late, you get paid for it: simple.

‘When I came back, I found out exception reporting does exist, and then tried to get people to do it, but there were so many barriers.’

As a resident doctor, Dr D’Sa notes: ‘We are trusted with lives on a day-to-day basis, and all the high-risk decisions that come with that. But when it comes to, “did you stay an hour late?” we’re not. In my mind, if you stay late, you should get paid – it’s that simple.

‘We’re not talking about staying behind 10 minutes here. It’s almost always going to be more than half an hour, often over an hour, and it’s happening all the time.’

Fear of repercussions

In the absence of any reliable dataset, Dr D’Sa set about collating her own, starting with a survey of resident doctors at a local trust in 2022. It provided some ‘damning data’.

‘It showed the scale of the additional hours doctors are doing. It showed the fact that there was a fear of repercussions because the process involved getting sign off from a senior, which was impossible because seniors didn’t have time to complete this process.

‘There were issues all along the way; people didn’t even have their logins, their rotas weren’t available, or their supervisor wasn’t there. There were about 100 reasons.’

Following a quality improvement exercise, she ascertained that ‘the process needs to change’, and on a national level.

‘The whole exception reporting process needs to be simplified,’ Dr D’Sa tells The Doctor. ‘It needs to be accessible, it shouldn’t have so many gatekeepers, it needs to go back to basics.’

After building the dataset in her region, she worked with RDC to take it across England, where exception reporting rules apply.

That England-wide survey concluded in October 2024, and its results – which Dr D'Sa hopes to publish in a medical journal – were used in negotiations with government that began off the back of the 2024 pay settlement.

'Overwhelming under-reporting'

Keith Farrell-Dillon, deputy co-chair of the UK RDC, with the terms and conditions portfolio, says the lack of exception reporting is a patient safety issue.

He says: ‘When you come to the end of your shift, you should be able to, in a structured manner, pass on to the next person. That breaks down where the system is understaffed.’

There is a ‘professional obligation’ on doctors to stay if they feel that leaving may put a patient at risk, he says, but notes that when exception reporting was first introduced, through the 2016 contract, the staffing crisis was ‘not as severe as it is today’.

Dr Farrell-Dillon says there has been ‘a lot of unhappiness’ among doctors who do not receive pay or time off in lieu for additional hours worked despite being entitled to it in their contracts. He says a ‘cultural issue’ to not claim has built up because consultants tasked with running a service feel like they are being undermined – because trust managers think the reporting is a result of their decisions – while resident doctors propping services up feel exploited.

‘A lot of people did not enjoy the conversations that became necessary,’ he says. ‘The answer that “there's too much work” is never one that's accepted because we're all expected to flex to meet our professional demands.’

The length of time it takes to make a report means ‘nobody likes the [current] system’, he adds. ‘You stay half an hour late and you have a half-hour meeting about it. That's a waste of your time and a waste of your consultant's time. You fill out a form for every single instance.’

Dr Farrell-Dillon says the situation led to ‘overwhelming underreporting’, as backed up in the England-wide BMA survey. ‘This was for lots of reasons,’ he says. ‘A sense of futility, lots of people were never given logins, people were made to feel like they were letting down their team or disappointing their consultant.

‘If you’re a medical registrar in a small specialty where your consultant’s reference is determinative to your outcome, you might value their support more than the time or money you’d receive for the additional work you’re doing. But that’s really quite perverse.’

He describes a ‘Potemkin village effect’ – a name given to a deceptive façade disguising an undesirable reality – whereby resident doctors don’t provide the data out of fear of being made to feel like troublemakers, so trusts don’t receive the data they need to solve staffing problems.

‘The intention was for [exception reporting] to be a mechanism to show there was an overload. It should be in everyone’s interest. But resident doctors are being culturally disincentivised by this conflict. Nobody should ever suffer detriment for accurately reporting the hours that they’re working.

‘You want to stay, to get the work done, but your profession requires you to do unpaid labour, and that leads to resentment. People are routinely told not to exception report, they are acculturated not to cause problems – but the numbers are quite horrific. It’s unsustainable.’

Dr D’Sa adds: ‘This goes beyond job satisfaction for doctors, it comes down to patient care.’

She notes how the survey focused on the issue of burnout among doctors, which leads to more time off sick, fuelling rota gaps that cause the burnout in the first place.

‘Our rotas are already 48 hours, and we’re doing these additional hours on top of that. We break the European working time directive quite a lot. We’re almost always running on minimum staffing levels. How can you provide effective care in that scenario?

‘When additional hours mount up, doctors are not getting time to sleep, eat, shower, basics like that. They’re driving home from work tired, knowing they’ve got on-calls. All that, then trying to make decisions on their next 13-hour shift about patients’ lives.

‘The NHS runs on the charity of doctors and I don’t think enough people realise that – that’s what this data shows. And we don’t really have a choice, because you can’t just leave a patient.’

Nobody should ever suffer detriment for accurately reporting the hours that they’re working

Keith Farrell-Dillon

Currently, a consultant, staff, associate specialist and specialty doctor or GP must sign off exception reports for resident doctors but many complain it takes up a lot of their time, which is already stretched. Under the new proposals, human resources will sign off exception reports for up to two additional hours.

All that resident doctors will have to prove is that they worked additional hours, within 28 days of the shift; they will not have to justify why they worked longer than their scheduled hours. All new starters must be given exception reporting access within seven days of starting a new post, at a new site or with a new employer. If not, rolling fines are issued to employers.

The method of providing the evidence for work done will be comparison of the doctor’s rota to a digital time-stamped proof of whereabouts.

Resident doctors are entitled to choose pay rather than TOIL (time off in lieu), unless TOIL is mandated for safety reasons such as ensuring sufficient rest after night shifts.

In the vast majority of cases, senior doctors will only be involved in the exception reporting process at a resident doctor’s discretion. Involvement might be if a resident needs senior support with a rejected report.

Exception reports of more than two hours will be investigated, but this will be for the purposes of maintaining safe staffing, not to contest a doctor’s judgment. Currently, in-person meetings are often required to assess reports, but under the new system meetings will only be necessary on rare escalations and can be remote.

In a bid to limit delays, trusts will be given seven days to process exception reports and face fines of £250 (rising to £500 after six months of implementation) for not providing access, failing to complete reports and data breaches – results of which will be published quarterly. RDC says a lack of financial punishment currently means contract terms are often ignored or unenforced.

HR will be able to ask resident doctors for clarifications. If a rejected claim is disputed by the doctor, it can be escalated in which case the guardian of safe working hours makes the final decision.

These reforms will also cover additional hours worked on mandatory training, non-clinical work such as audit or quality improvement, and anything else required for an ARCP (annual review of competency progression).

A workable system

Dr Farrell-Dillon says doctors appreciate that ‘the nature of healthcare is that workload is not necessarily well predicted’ but insists that doctors should be remunerated for the hours they work.

Ensuring enforceability was also an important factor in negotiations. ‘Just because something is in the contract, doesn’t mean it happens,’ he says.

Making the proposals workable for trusts was also key, he adds. ‘It should always be cheaper to implement the system the way it should be,’ he says, incentivising trusts to adhere to contracts rather than paying fines for failure.

Reducing in-person meetings will be ‘a shift to the 21st century’, says Dr Farrell-Dillon. ‘We’ve all been through COVID, we know how to do Zoom calls now.’

The same goes for the ‘technical solution’ for proving additional hours, which is likely to be ‘something simple’, such as a timestamped geolocation, like a screenshot of Google Maps, sent to a trust email address: ‘The more complicated we make this, the slower it’s going to be.'

Dr Farrell-Dillon says stripping back the process to the basics will be beneficial for all involved, be it trusts understanding their staffing difficulties more accurately, or consultants reducing their admin, and will give trusts an opportunity to boost productivity – something for which health secretary Wes Streeting is pushing hard.

Dr D’Sa says the changes need to be communicated well, for example to IMGs (international medical graduates) who are new to the NHS, many of whom she says are ‘not told the rules’.

‘There’s never anything clearly written, supported by someone who says they will back you. People fear that when it comes to supervisor meetings or portfolio meetings their exception reporting will be used against them.’

Resident doctors, IMGs and UK-trained, often feel judged by senior doctors for making exception reports even though it was the safest clinical decision, Dr D’Sa says.

‘Handovers, with all their intricacies, take time. Supervisors, who have to approve your request, might say “why didn’t you just handover and leave?” and make you feel like you’re not good enough – but that’s not the situation.

‘We’re understaffed, overworked, and have a lot of patient burden. We’re constantly running at 100 per cent, and the majority of doctors are doing their best – so to suggest they’re not working hard or fast enough is demoralising.

‘If consultants end up under fire for approving exception reports, they’re going to question them. And if a head of department is getting a lot of exception reports they are going to get penalised. But people need to stop blaming each other, and realise the underlying problem, that we’re understaffed.

‘Rather than high levels of exception reporting meaning a department is not doing well, this should be looked at through the lens of: this department clearly needs help, needs more doctors on the rota.’

Dr Farrell-Dillon agrees an underreporting culture exists but says ‘a lot of consultants are very supportive’ as well. ‘This has never been “your consultant will punish you”, it’s always been “what if the wrong consultant hears about it”,’ he says.

Consultant support

Consultant anaesthetist Dr Helen Neary, co-chair of the BMA consultants committee, says consultants support the changes to exception reporting, which she hopes will result in more resident doctors ‘feeling able’ to submit them.

She said she would always encourage resident doctors to exception report so that they were fairly paid but accepts that in some instances requests can create ‘tension’ between residents and consultants.

Moving the sign-off process to HR could see ‘a real improvement in the relationships’ as well as saving consultants’ own time, Dr Neary told The Doctor.

She acknowledges that fear of repercussions has been a ‘real worry’ for resident doctors in some trusts and that exception reporting ‘just hasn’t happened’ as a result. The low number of reports she sees through her own local negotiating committee, are ‘extremely surprising, knowing how often trainees work more hours than they are scheduled to’.

Having to question resident doctors, who in turn must ‘justify’ their additional hours or missed training opportunities, adds ‘a layer of confrontation’, Dr Neary suggests.

‘Consultants, like everyone in the NHS, are really, really busy. Finding the time to go through exception reports and speak to residents is quite time-consuming. This will help free up the administrative burden.

‘From a resident’s point of view, the timescales for getting the exception report reviewed, meeting and addressed, is so prolonged that I can see why many think it’s not worth the time.’

Dr Neary says that, despite exception reporting being brought in to identify systemic issues such as rota gaps, some consultants can take exception reporting ‘quite personally’ which can make relationships with residents ‘challenging’.

She adds: ‘Resident doctors are trusted with life and death decisions. If we can trust them to do that, we can certainly trust them to know how many hours they’ve worked.'

Dr Neary says the data gathered from February should be used ‘constructively’ in order to provide evidence to ‘address some of the difficulties with staffing’.

‘If regular exception reporting is handled by HR, then HR will be able to pick up the patterns of staffing issues then work with the consultants on the reasons. Then we can address things with an evidence base.’

She also believes the new agreement adds some ‘teeth’ to the process, in that trusts will face ‘consequences’, such as financial penalties, if they don’t comply with legitimate reports.

Surgical specialties

Reforming the rules on exception reporting, while universally welcomed among the profession, may work to varying degrees in different specialties.

This could be down to factors such as training opportunities, and different cultures of presenteeism across specialties.

The national survey data showed that resident doctors in surgical specialties, neurology, stroke medicine, renal, gastroenterology, urology, and ophthalmology have a greater fear of backlash from seniors or departmental managers.

Dr Farrell-Dillon, a surgical trainee, says being on a surgical pathway is often ‘viewed as a privilege’ and this disincentivises exception reporting.

He expects ‘there will be many surgeons who do not exception report’ after the changes come into effect, but says: ‘The point is that it will be their choice.

‘The win of these reforms is to say if you want to do this, you should be able to do this without the fear of detriment.’

Dr Neary, a consultant anaesthetist, says residents working additional hours in theatre ‘might be there for something that is really important to their training’.

Resident doctors are trusted with life and death decisions. If we can trust them to do that, we can certainly trust them to know how many hours they’ve worked

Helen Neary

‘Trainees value their time in theatre, so may not exception report those instances if it adds friction points with their consultants,’ she says. ‘But that is still working, so from my perspective they should be entitled to exception report and be paid for those additional hours or get time back in lieu. I would have no problem signing the exception report.

‘Hopefully the new system means that those specialties start to exception report more than they did. Medicine is not a nine to five profession. We all have out-of-hours working and accept that we might not be able to clock off at 5.30pm on the dot. But if someone stays to 7.30pm, they shouldn’t have their professionalism questioned just because they want to be paid for it.'

There is also a drop off in exception reporting as doctors progress through their grades from their foundation years to registrar. The national survey data showed an exact correlation between increased training grade and reduced reporting frequency.

Dr Farrell-Dillon puts that down to how people are ‘acculturated into the modern NHS’. ‘You are taught that this is normal,’ he says. ‘You may not accept that it is right, but you are taught that it is normal.'

Feeling valued

Dr D’Sa believes a functioning exception reporting system will overhaul the way doctors feel towards their employers, and the respect they feel as professionals.

‘In Australia, I felt so rewarded for being a doctor. I felt valued. And that completely changes your perspective when you come to work and how you feel at work versus here [in the NHS] where it feels like nobody has time to care because they’re busy trying to survive the system.’

She says routine unpaid additional hours is one of the main reasons for doctors feeling undervalued, although it is not the only one – expectations to rotate across the country also feature high.

‘You’d be surprised what a difference it makes when you come to work and feel valued,’ she says. ‘We all want to do this job because we enjoy it, but all those little things make a difference.’

‘In Australia, if I stayed 20 minutes late, I’d get a thank you. Here, it’s often just “oh, you should have better time management.” It feels like a blame game. That’s a whole culture change that needs to happen, including at a management level.

‘We shouldn’t shy away from paying doctors for the hours they have worked or say they shouldn’t report half an hour. Half an hour five days a week is two and a half hours.

‘If the changes are taken seriously, it could completely change the morale of doctors. It could change patient care for the better and it could reduce burnout, staff sickness levels, the relationship between consultants and resident doctors, and perhaps even management.’

Dr Farrell-Dillon is encouraged by the negotiated reforms, saying, ‘there are individuals at both NHS Employers and the Department of Health and Social Care who have clearly demonstrated that they want this to succeed’.

With talks with the Government on the level of pay resident doctors receive continuing, progress on exception reporting can be seen as a win for both sides.

The cultural change may take longer.

As Dr Farrell-Dillon puts it: ‘You don't want to be the one who left early when other people were suffering. People stay late because they're team workers. That's part of our psychometrics.

‘But we should be paid for it as well.’