From bad to worse: Northern Ireland's care crisis

From bad to worse: Northern Ireland's care crisis

If ‘crisis’ sums up the health service in England, Wales and Scotland, then perhaps we need to invent a whole new word for Northern Ireland, where Jennifer Trueland hears how patients can wait five years for an appointment

On almost every measure, Northern Ireland’s health and care system performs worse than anywhere else in the UK. Waiting lists are proportionately much higher and rising – with more than half waiting more than a year even to get an outpatient appointment.

Waits of five years or more for an initial outpatient appointment are not uncommon, doctors say, with patients then languishing for the same time again on a waiting list for treatment. Many die before they reach the top of the list.

General practice is also in crisis with growing numbers of practices either closing or at risk of closure – official figures show there were 319 active practices at 31 March 2022, compared with 350 in 2014. The situation is even more acute in the west of the country, which has seen a drop of 16 per cent.

There is also a shortage of doctors in primary and secondary care – putting more pressure than those who remain in post, many of whom are retiring early, or considering it.

So why is the situation so bad in Northern Ireland?

‘The simple answer is capacity,’ says Alan Stout, chair of the BMA Northern Ireland GPs committee. ‘We just have not planned capacity and workforce well enough. We’re short of GPs, we’re desperately short of nurses, we’re short of most hospital specialties.’

Waiting lists are, to an extent, a symbol of a system that isn’t working properly. But they also affect the lives of people, whether they are waiting for treatment themselves, or working in Northern Ireland’s HSC (health and care services).

Faced with the prospect of lengthy waits for even life-saving treatment, some are choosing to pay even where they can’t really afford it, while others simply don’t have the choice.

It’s a scandal, says Dr Stout, but patients have come to expect this is the way things are. ‘You can refer to many things in medicine as learned helplessness. That’s what our population has at the moment – they just have an expectation and a helplessness that they’ll be on a waiting list and that they’re going to be on it for years and years, because it’s been going on for so long.

‘It’s amazing – if it were anywhere else, people would be on the streets campaigning, whereas here we just seem to accept it, literally.’

Political strife

The rest of the UK also has capacity problems and tight resources, and, like Northern Ireland, has been grappling with a pandemic for the last two and a half years. So what makes the situation particularly bad?

According to David Farren, chair of the BMA’s Northern Ireland consultants committee, there are several factors at play, not least the political situation. Devolution is suspended because the main parties cannot agree to power-sharing, largely owing to disagreements on Brexit and the Northern Ireland protocol. This means, effectively, the health department has very limited decision-making powers.

‘Our Assembly hasn’t sat for the majority of the time it’s been there – so political decisions haven’t been made,’ he says. ‘We’ve not been able to form a budget for more than a year.’

There are very few things that will lose votes like closing down a hospital or a service

Dr Farren

This is something that also frustrates Dr Stout. ‘It’s had a massive, massive impact, the current one [suspension of devolution] in particular, because we had a tantalising glimpse of a multi-year budget, which is absolutely fundamental to doing things differently.

And not only did a multi-year budget get taken away from us, but an actual proper in-year budget has been taken away from us. So what happens is that as a system, you just revert to firefighting and dealing with crises and problems as opposed to actual, proper planning.’

Successive attempts at rationalising hospitals and services across Northern Ireland have failed, partly owing to the lack of a functioning Northern Ireland Assembly, but also because of political nervousness.

Politicians are afraid to close hospitals local to their or their colleagues’ constituencies, says Dr Farren. ‘There are very few things that will lose votes like closing down a hospital or a service. We’ve been calling for years for the politicians in Northern Ireland to have a big conversation with the public to explain that, for example, you might wish to have your baby in the local hospital, but it doesn’t have all the services that you and your baby might need. And that you’re better travelling a bit further and having all those services near you.’

Patient voice

The Doctor requested interviews with the then health minister, Robin Swann, and the chief medical officer Michael McBride. The Department of Health said neither was available.

As well as doctors and members of the public, The Doctor spoke to Ruth Barry, senior policy impact and influence manager at the PCC (Patient & Client Council). This arms-length organisation represents the interests of the public, by individual advocacy (supporting individuals in their interactions with health and social care services), but also in engagement and campaigning to promote the patient voice.

Unsurprisingly, the PCC reports growing demand for its services, with its small team handling 6,195 calls via its freephone service between April 2020 and March 2021.

One of the top areas of concern is access to general practice, she says, and the PCC is working with the BMA and others to try to address this.

‘We want to work in partnership with the BMA and Royal College of GPs and other organisations to try to find solutions to the issues. What’s absolutely key for us is that the patient’s voice must be at the centre and in our work, we’re relaying the patient experience.’

Health is too important to be a political football, and we need to prioritise health for everyone

Dr Farren

Perhaps backing Dr Stout’s point about population acceptance, relatively small numbers of patients have contacted the PCC about lengthy waits, she says – around 15 to 20 in the last six months.

‘In a handful of cases we were able to make a difference in terms of expediting the waiting, but that’s not to say that’s something you can do in every case. And if they want to make a formal complaint or raise a concern, we support them to do that.’

Whether or not patients are making formal complaints about it, lengthy and chaotic waiting lists mean extra work for health services, including general practice, says Dr Stout. He describes the situation of one patient who needs surgery to remove a gall bladder.

While on the waiting list, she has had at least 27 contacts with health services, including five trips to emergency departments and duplicate tests and scans. ‘We all know she had gallstones and needed the surgery… it’s crazy,’ he says.

Pensions deterrent

Meanwhile, workforce shortages across all branches of practice are only likely to worsen, as more GPs and consultants retire – many early – driven away by relentless pressure and other challenges such as punitive pension taxes. The number of GP practices is falling, as patient numbers increase, and consultant vacancies continue to rise.

Dr Farren doesn’t sound optimistic that things will get better any time soon. ‘Every time we have an election, the BMA will hold a hustings, and every candidate will say that health is too important to be a political football, and we need to prioritise health for everyone in the nation. And then after the election, health will be the last ministry to be appointed because nobody wants to poisonous chalice.’

He believes caretaker minister Robin Swann did an ‘amazing’ job throughout COVID, but warns: ‘If we ever form another Government again in Northern Ireland we’ll have a different minister. And we’re concerned that it will go back to the same old, same old, trying to eke out the same service, with the same level of activity, while spread too thin, with exhausted staff.’

General practice

The word crisis is often bandied about in medical circles with varying degrees of exaggeration. But few would even try to deny that general practice in Northern Ireland is in crisis

Battered by workforce shortages, soaring demand, poor infrastructure and the lack of a decision-making Northern Ireland Assembly, many practices either already have or are at risk of closing or handing back their contracts.

Even initiatives designed to improve services, such as supporting practices with multidisciplinary teams, have stalled owing to a lack of funding – and political paralysis.

This is playing out against the background of a health and social care system with unprecedented waiting lists and an acute health system in desperate need of overhaul.

Not surprisingly, all of these factors are having an effect on GPs, as Alan Stout, chair of Northern Ireland’s GP committee knows only too well. He blames a lack of capacity and planning – and says system pressures, such as a record waiting lists, are a big issue for general practice as well as for secondary care.

You just get this complete chaos of a system and nobody knows what’s happening

Dr Stout

It doesn’t help that nobody really knows what the true waiting-list figures are, he says. ‘There’s a quarterly figure that comes out and it’s absolutely nonsense: because it’s not broken down into any details it's meaningless. The bigger the figure is, the more chaotic it is because nobody knows who is on a waiting list, nobody knows what waiting list they are on.’

He believes the waiting list has duplicates because people might have been referred more than once for treatment – or they may have paid for treatment, but not been taken off the list. ‘You just get this complete chaos of a system and nobody knows what’s happening.’

It’s difficult for GPs, he adds, because they can only refer to one waiting list, with no choice either for them or the patient. And the waiting times are excruciating. ‘If someone comes to me, and they’re really struggling with osteoarthritis, and need a hip replacement, then they will be placed on a waiting list for five, six, seven years simply to be seen, and have that confirmed, then put on another waiting list for an operation, which will be another five, six, seven years.

‘We have patients dying in pain because they’re not being treated. And as GPs, what we see is that they keep coming back to us and we do everything we can to help them, with stronger and stronger medication, but you see them struggling, you see them get weaker and weaker, they might need [social] care. And for some, when they’re time comes around – if they are still alive – they are no longer fit for surgery. It doesn’t make sense in any way, shape or form.’

Duplicated work

The lengthy and chaotic waiting lists mean extra work for health services, including general practice, as well as being frustrating for patients, he adds.

‘I had a patient come to my surgery who has gall stones – they told me they were having terrible trouble and hadn’t been operated on. So I decided to look back at everything that had happened to them.

'They were initially referred from our practice for general surgery because it was gallstones and they just wanted to get them on the list. Subsequently they had umpteen bouts of acute cholecystitis – some real flares of it – so they had been in the emergency department on five separate occasions.

'In the interim, they had also come back to our practice, and somebody said that as they’d been waiting so long, let’s at least confirm [it’s gallstones] and get an ultrasound, and referred them. They’re still waiting for that ultrasound, but in the emergency department they’ve actually done the ultrasound and confirmed they have gallstones.

'They had gone to a different emergency department on one occasion – because this is a difficulty in Northern Ireland, we’ve got so many hospitals – and they had referred her to their own surgical team as well.

'So this was a middle-aged patient, and we all knew they had gallstones, and I think I counted around 27 health contacts between us first knowing they had gallstones and when I decided to review the record.

'The patient was sitting on five different waiting lists – so every time they count the waiting list, they are counted five times. It’s crazy.’

'You revert to firefighting and dealing with crises and problems as opposed to proper planning'

Dr Stout

The other big issue is that Northern Ireland desperately needs to rationalise its hospitals and specialist services. Subsequent reviews throughout the decades have all recommended transformation, most recently the Bengoa review, of which Dr Stout was a panel member.

Among much else, the review recommended stabilising elective waiting lists, growing a supporting primary care, and transforming social care.

‘These are big areas, but the concept behind it was that you can’t really transform if you don’t get your foundations right,’ says Dr Stout. ‘But in the six years since Bengoa, we’ve failed in terms of those core foundations. We’ve failed to get the basics right.’

One reason for this failure is the repeated suspension of devolution in Northern Ireland, which again does not have a functioning assembly.

‘It’s had a massive, massive impact, the current one in particular, because we had a tantalising glimpse of a multi-year budget, which is absolutely fundamental to doing things differently.

'And not only did a multi-year budget get taken away from us, but an actual proper in-year budget has been taken away from us. So what happens is that as a system, you just revert to firefighting and dealing with crises and problems as opposed to actual, proper planning.’

Change is slow

There has been some positive change, such as the introduction of multidisciplinary teams in general practice. ‘This is what we need, but it’s too slow,’ says Dr Stout. ‘So what we’ve done is that we’ve created more health inequality with what is supposed to be the solution, because some places have them, and some places don’t.’

Another positive development has been the rescue teams, which – as the name suggests – support practices that are struggling. This is happening via GP federations, groupings of practices working together at scale to benefit their local populations. Yet still practices close, or hand back their contracts, while others struggle to find GPs and other staff to work in them.

At the time of writing, around 70 practices had been referred to the GP rescue team since it was established last year – and around a third of these were deemed at risk of collapse.

We’ve got a really, really good bunch of people who will bend over backwards to make it general practice work

Dr Stout

All of these issues were raised at roadshow meetings organised by the BMA in September, an in-person event at a hotel in Belfast, and a virtual event to which all GPs were invited.

The frustration in the room was palpable, with many expressing real anger at the current situation, and what they saw as the health department’s refusal to take meaningful action to make the situation better.

Dr Stout knows how much anger is out there, and he also knows that the GP workforce is exhausted and, in many cases, disillusioned.

‘We’ve got a really, really good bunch of people who will bend over backwards to make it [general practice] work. But that's what's harming them now, they have been too accommodating, too willing to try and deal with every issue themselves, and it's really hammering them.’

Junior doctors

Workplace rights can be scant, which has led many doctors to leave Northern Ireland for sunnier climes

Andrew Wilson, chair of the BMA Northern Ireland junior doctors committee, is in his car heading out to do a home visit. In his third year of GP training, based at a practice just outside Derry, he sounds enthusiastic about his job and about being a GP.

He is also careful to point out that, in many ways, Northern Ireland can be a great place to be a junior doctor, with many excellent departments, a good variety of patients, and supportive senior colleagues.

But it’s also a place where, in many cases, basic workplace rights – such as facilities and getting rotas on time – simply don’t exist. And where, exhausted by the pandemic, junior doctors are voting with their feet and choosing to leave.

‘Junior doctors are struggling,’ says Dr Wilson. ‘They are facing rota gaps, working additional unpaid hours, and don’t even have basic workplace rights such as timely rotas and adequate facilities.

‘I’ve had several friends go abroad, mainly to Australia, looking for a better work-life balance, and unfortunately some haven’t come back. They say they are paid better, they have better contractual provision, there’s less rota gaps, there’s less pressure on them to cover unfilled gaps.

Northern Ireland’s health problems are multi-factorial, he says. There’s the political dimension – the stop-start nature of devolution during the last two decades is perhaps one explanation why juniors are still working to the 2002 contract.

As with their counterparts in the rest of the UK, juniors in Northern Ireland have faced years of pay erosion, and, at the time of writing, NIJDC is planning to seek feedback from members about their pay, terms and conditions, including whether they want to follow their colleagues in England into balloting on industrial action.

‘There’s a lot of frustration in Northern Ireland but it’s not purely based on pay,’ he says.

‘Obviously everyone is concerned about pay erosion, but it’s not just that. It’s other terms and conditions of service as well. It’s the rota gaps, it’s getting your leave, it’s getting your rota on time. It’s the basic things like being about being able to take breaks.’

Support exists

Dr Wilson, who studied medicine in Edinburgh, stresses that there are positives about working in Northern Ireland.

‘There are some very good trusts, and very good departments – and then there are those that aren’t. I think training in Northern Ireland is very good. We’re exposed to a wide range of cases and overall there’s a lot of support from senior doctors.

‘But we need more doctors and we need more focus on retention of current staff. We all went into medicine to do the best for our patients and I’d love to see the waiting lists being tackled and more funding being allocated to healthcare. That’s what we all want to see happen – and it needs to happen now.’

SAS doctors

Staff are looking forward to retiring but who will replace them while demand is so high and the appeal of the job so low is concerning

As an associate specialist in emergency medicine in Belfast, Siobhan Quinn used to love going to work. Now she finds it ‘disheartening’.

It’s not just the prospect of overcrowded clinical areas – although that doesn’t help. It’s not only because it’s now taking three days, in some cases, for patients judged as requiring admission to get a hospital bed. What really hurts, she says, is the sense of feeling disempowered, undervalued, and as if it’s impossible to do the job she wants to be doing.

‘I used to love my job and really felt valued and that I was able to help patients and contribute to their care. But in recent years, I’ve started to dread going into work. Myself and my peers are now very focused on retirement – while I don’t want to wish my life away, what we talk about is when can we retire, when can we leave this job.

'But the worrying thing is that I don’t know who is going to come behind me, and take my place, so there’s going to be even more shortages than there are at the moment.’

As with the rest of the UK, patients attending emergency departments in Northern Ireland are waiting way beyond target times to be seen and, where required, admitted.

Perhaps tellingly, publication of statistics relating to the latest quarter was delayed ‘due to staffing changes/pressures within the branch’, according to the Department of Health website.

But figures for April to June of this year show that the four-hour target (for discharge or admission) was met for just over half (51.5 per cent in June) of those who attended.

- June 2021: Number of patients spending more than 12 hours in an emergency department: 5,488

- June 2022: Number of patients spending more than 12 hours in an emergency department: 8,192

But behind these statistics are despairing doctors. ‘We have around 50 clinical spaces and this morning we had 68 patients waiting for a bed – you can imagine what our department looks like,’ says Dr Quinn.

‘Ambulances queue outside because there’s no trolley to put patients on. There’s a lack of dignity for patients and it's demoralising for staff. It’s really disheartening.’

There’s no privacy, no dignity. That has an effect on patients

Dr Quinn

The statistics simply don’t show what’s actually happening, she says, adding that it’s hard to describe.

‘Doctors have safety concerns for the patients because when they are started on some treatment, it’s very undignified for them waiting in the department, lined up against each other. There’s no privacy, no dignity. That has an effect on patients, obviously, but also on the medical staff and nursing staff. There’s a moral injury that we face whenever we’re not able to give the patients the treatment they deserve and need.’

A friend – also a doctor – recently witnessed it for herself, when her mother was a patient, says Dr Quinn. ‘Her mother was being looked after in a three-bedded area where there were eight trolleys. She was horrified. She did ask me to compliment the nurses on the care they gave her mother, but she couldn’t believe how undignified it was. She’d heard me describe it, but until she saw it with her own eyes, she didn’t actually comprehend what I was trying to describe.’

The overcrowding is not because patients are attending emergency departments when they don’t need to, she adds, but because of delays in admission for those assessed as needing it.

‘They’ve closed beds, believing that not all people need to be inpatients,’ says Dr Quinn.

‘Now that’s true, but at the same time, as far as I can see, they’ve not increased support in the community, and community staff aren’t valued as much as they should be. A lot of patients would prefer to be at home but the support isn’t there.

‘The people who are in our emergency department are not the people who say they can’t get an appointment with their GP. They are people that we have seen, who are sick enough to need admission to hospital, so more GP appointments wouldn’t help that. We need action across the whole system, and in the short term, it’s important to make more inpatient beds available.’

Locum use

Staffing shortages mean that emergency departments are overly reliant on locums, she adds. This is the case for staff, associate specialist and specialty doctors as well as for consultants. Although measures to improve working conditions for SAS doctors – such as a new contract that recognises seniority – have been introduced, they’re not making a difference on the ground.

‘Trusts are really slow to advertise new specialist jobs so that’s really demoralising for a lot of specialty doctors,’ she says.

SAS doctors have also been reluctant to transfer to the new contract because it lengthens the ‘normal’ working day, and because doctors on the new contract were not offered the pay review body-recommended pay rise.

‘It’s not all about pay, but that’s obviously something to consider,’ she says.

Her son has just applied to study medicine – and she worries about his future. ‘I didn’t suggest it to him; he came up with the idea himself, albeit very late in his secondary school career, and he hasn’t done the right subjects.

'But he is applying for medicine, and I’m really quite anxious about him doing that. I just hope that there will be changes and he’ll be able to find something where he feels happy and fulfilled.’

Consultants

The health service is too underfunded and understaffed to deliver the service expected of it

When colleagues from the rest of the UK bemoan their lengthy waiting lists, David Farren can only sigh. As chair of the BMA Northern Ireland consultants committee, his constituents are working in a system where they not only have – proportionately – the highest number of people waiting, but they are also waiting longer.

What’s more, consultants in Northern Ireland are paid less than their counterparts elsewhere in the UK, and are struggling to keep going in an over-stretched system with not enough staff and too many hospitals. In addition, the lack of a functioning Northern Ireland Assembly suggests there won’t be a political solution any time soon.

While the pandemic has exacerbated these problems, it did not cause them, says Dr Farren, a consultant microbiologist and infection control doctor.

‘For as long as I can remember – and I qualified in 2002 – Northern Ireland’s waiting lists have been the worst in the UK. A consistent message from the BMA has been that the health service in Northern Ireland has been underfunded for the service it is expected to deliver and understaffed for the service it is expected to deliver. And it is stretched across multiple sites, both in primary and secondary care.’

Multiple reviews have demonstrated that Northern Ireland has too many hospitals, he adds. ‘We focus on where the hospitals are rather than what services we need and how they need to be set up,’ he says.

Part of the reason for this is infrastructure and poor transport links, but it is also down to a lack of investment and failure to forward plan, he adds.

The BMA has also been calling for an expansion in staff numbers. He cites information obtained by BMA Northern Ireland via freedom of information requests showing that consultant vacancies were actually running at around 14.9 per cent, rather than the 6.7 per cent claimed by the health department.

‘That was in September 2021. Since then we’ve had problems with pensions taxation and to be honest, people who have lived through the two most difficult years that we’ve had in the health service in my time working in it, and they’re burnt out, feel unappreciated and under-valued and are looking at retirement. We’re losing a huge number of very experienced staff.’

Politicians are afraid to close hospitals local to their or their colleagues’ constituencies

Dr Farren

The big problem, he says, is that recommendations of multiple reviews have never been enacted. ‘Instead we try to keep every place open, limping along, even though we can’t staff them properly.’

It doesn’t help, he adds, that consultants in Northern Ireland are paid less than those in the rest of the UK and that makes attracting new staff very difficult.

‘We’ve had a freeze on clinical excellence awards for the last 10 years. If you have two jobs side by side, one of which requires a flight over the Irish Sea, and the other doesn’t, and it’s paid more, you know you’re going to vote with your feet and go for the one closer to home.’

‘Politicians are afraid to close hospitals local to their or their colleagues’ constituencies,’ he says. ‘There are very few things that will lose votes like closing down a hospital or a service.

'We’ve been calling for years for the politicians in Northern Ireland to have a big conversation with the public to explain that, for example, you might wish to have your baby in the local hospital, but it doesn’t have all the services that you and your baby might need. And that you’re better travelling a bit further and having all those services near you.’

The Troubles' shadow

These buildings could be repurposed as elective-care centres, for example, or GP out-of-hours centres, he adds.

The legacy of the Troubles is also a continuing issue, he says, not least in the mental health of the population. ‘We have a large number of people on antidepressants – I believe it’s the highest in the UK. We also have the highest rates of post traumatic stress disorder.’

There are other region-specific health issues, he adds – for example, Northern Ireland previously had a large tobacco industry, and a manufacturing base where many workers were exposed to asbestos and other carcinogenic substances.

You could, of course, say much the same for swathes of mainland Britain – but where Northern Ireland is distinctive is in its political situation.

‘The other big challenge is that our Assembly hasn’t sat for the majority of the time it’s been there – so political decisions haven’t been made. We’ve not been able to form a budget for more than a year.’

No extra investment

As a microbiologist and infection control consultant, he knows how frustrating it is for his colleagues to have to cut back on the work they do because infection control processes mean procedures can take twice as long as they would have previously, he says.

And while the rest of the UK has put in extra investment to tackle the elective care backlog, Northern Ireland hasn’t been able to do that.

‘We haven’t had the budget to say we can put on additional lists or sessions to catch up – and the size of our waiting lists is so long that we couldn’t fix them.’

As with the rest of the UK, consultants in Northern Ireland have been retiring early as a direct result of punitive pension taxation. One well-known figure, nephrologist and former Northern Ireland council chair John D Woods, tweeted in August that he was retiring after 36 years in the NHS ‘solely due to pension taxation’.

Another, Anne Carson, until recently a consultant radiologist and deputy chair of the BMA in Northern Ireland, has also taken early retirement. The Doctor reported on her warnings on the pensions issue in 2019.

Others are also considering drastic life changes. One consultant who didn’t want to be named believes the situation is untenable, but nothing new.

‘I have family members thinking of moving to Scotland because, effectively, we don’t have a functioning health service here,’ he says.

‘Yes, our figures are much worse than in England, but that was the case before COVID too. It’s just the latest excuse. Speaking as a Northern Ireland citizen, and a prospective patient, we have a disastrous situation here.’

The public

The Doctor correspondent Jennifer Trueland meets people and patients to gauge how they feel about the standard of the healthcare service

On the bus towards a Belfast suburb, I fell into conversation with two older ladies. They were travelling home after visiting City Hall to sign the book of condolence for the late Queen Elizabeth.

What was I doing in Northern Ireland, one asked. ‘Writing about the health service, you know, things like waiting lists,’ I said.

It was as if I’d turned on a tap – I didn’t even have to ask, it just flooded out.

She had worked in the health service, she said, but was now retired. Last year she had a problem with her eye, and was told she would need an operation.

She was in discomfort, and worried about her sight. But she was told she’d have to wait a long time, even to get an outpatient appointment, let alone the surgery she required.

Going private

After anguished discussions with her family, she eventually decided to have it done privately. It was £180 for the initial consultation, she said, seemingly far more outraged by that than by the £400 to carry out the day case procedure.

There was a similar response from other people who asked why I was visiting (people did seem very prepared to ask questions of a stranger). The previous evening at the beautiful Grand Opera House, a retired teacher and her daughter, a lecturer, told me of the problems they had getting a GP appointment. Practices in neighbouring areas had closed, they said, so their own local surgery was now overwhelmed.

Then there was the woman in her 40s, who had been waiting seven years to have a kidney removed. She’d had two pre-meds over the years, she said, but the surgery had never taken place.

It wasn’t all negative. A friend who lives in Mid-Ulster sang the praises of her local practice which had been quick and responsive when her husband had a health concern. There was a similar story from a young mother with an ill child – no messing about, the child was seen and treated within hours.

Reduced to tears

But on what was necessarily a short trip to Northern Ireland, there are several impressions that stick. There was the GP who couldn’t keep back the tears when she described how her practice was left with no option but to hand back its contract.

There was another GP whose face greyed with despair as he told me how he had referred a patient with serious colorectal symptoms who needed urgent investigations – months later, the patient was still waiting.

Then there was the woman I got chatting to in my B&B in Derry. She was staying there while she visited her son, a junior doctor at the local hospital. She described how he was working far beyond his rota-ed hours because, as he told her, he couldn’t leave the wards without a doctor.

One night he didn’t finish until 1.30am, after starting at 7am the previous day. Again, she was almost in tears. ‘What can I do?’ she asked. (I suggested exception reporting and BMA membership).

And back to the woman on the bus and her eye operation. This was not the tale of someone who could easily afford to pay, for whom ‘going private’ would ever be the go-to solution.

She feels that she was lucky to be able to make that investment in her sight. But she now dreads that the other eye might be going the same way. She’s not sure what she’ll do then.

'I know them, and they all know me'

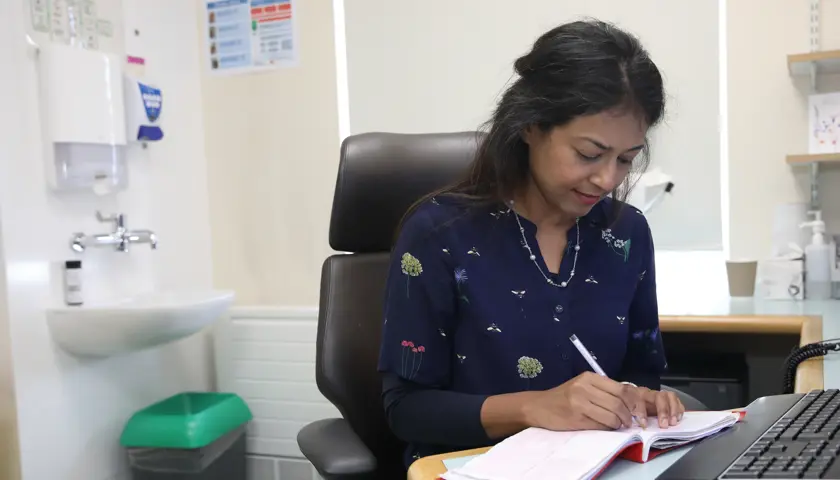

Derry GP Tom Black has installed himself in the heart of a community to meet its healthcare needs

When Tom Black arrived at his practice in Derry’s Bogside area on a particular Friday morning, there was already a patient waiting in the car park. A young mum was worried about her child, who was having a bad asthma attack. She didn’t want to go to hospital – so she relied on her local GP.

Like most in the UK, the Abbey Medical Practice currently runs a telephone triage system, and on this morning in particular, was running telephone clinics that were supposed to be for emergencies only, as it was just ahead of a bank holiday weekend.

But what are you supposed to do when you have a clearly ill child – and desperately concerned parent – in front of you? Even when you know that treating the patient will put you behind before the day has even begun.

Dr Black, chair of the BMA in Northern Ireland, is senior partner at the practice and clearly loves it and the community it serves. ‘These are all my people,’ he says, gesturing at rows of houses and flats as we drive through the historic city, the second largest in Northern Ireland. ‘I know them, and their families, and they know all know me.’

This intimate knowledge of the patient population is evident as the morning clinic proceeds. Dr Black barely seems to need to refer to the patient’s notes in front of him as he enquires about people’s families, asks for updates on previous conditions – and really listens to what patients say.

Some of the calls seem to stretch the definition of ‘emergency’ to the point of [my] incredulity, but he is unfailingly courteous and the patients on the other side of the phone audibly relax as he dispenses wisdom – and usually a prescription.

Patients in his practice tend to be at least 10 years older, biologically speaking, than their actual years, he explains, so experience all the multiple morbidities of older age when they are much younger than in the general population – even in Northern Ireland, which has the lowest life expectancy in the UK.

Sometimes patients get quite indignant with him when he tells them his age, and they realise that he’s as old or older than them – and certainly he carries his 63 years lightly. ‘They tell “you’re very fresh” – that’s the word,’ he laughs. ‘I tell them it’s because I gave up smoking at the age of 25.’

Today the Abbey Medical Practice is thriving and busy with six GP partners (four whole-time equivalent), experienced managers and receptionists, nursing staff and access to an extended multi-disciplinary team, including pharmacists, a mental health practitioner, physiotherapy and social workers. Yet within the last five years, it was on the brink of closure. A spate of retirements meant they were down to three doctors and were, Dr Black says, in crisis. They got through it, with help from the Northern Ireland GP rescue team. A key factor in that survival was paying locums and salaried staff ‘a fortune’ until they could recruit sufficient partners.

On this particular Friday, there were two partners officially working, including Dr Black. But it was notable that another partner had popped in to check up on some scans, and that even when the two GPs on duty grabbed a short coffee break, they each carried with them a sheaf of prescriptions to be signed.

After morning surgery, each GP set out on a home visit before an afternoon of more calls and in-person consultations in the surgery. Clearly it irritates Dr Black that there remains a perception that GPs aren’t seeing people face-to-face, and the common belief that home visits are a thing of the past.

‘Home visits are easy,’ he snorts. ‘You get in the car, get the radio on, drive to see one patient, then get in the car, radio on, same again, and you can only see a few patients.’ That’s easier than a morning chock-full of telephone consultations – some of them requiring significant follow-up action.

Spending a few hours in a practice obviously only gives a snapshot – a moment in time – and can’t tell the whole story. But the overwhelming impression at Abbey Medical Centre is of a team that is working hard, really hard. It’s also a practice which is very much part of its community. And, presumably like every other practice in the UK, its doctors have to sign a hell of a lot of prescriptions.

- Until September 2024, resident doctors were referred to as ‘junior doctors’ by the BMA. Articles written prior to this date reflect the terminology then in use