At the end of the line

The intense and unsustainable pressure often faced by GPs working out of hours is not inevitable. Peter Blackburn visited OOH services around the country and heard how proper investment could transform the experience for doctors and patients alike

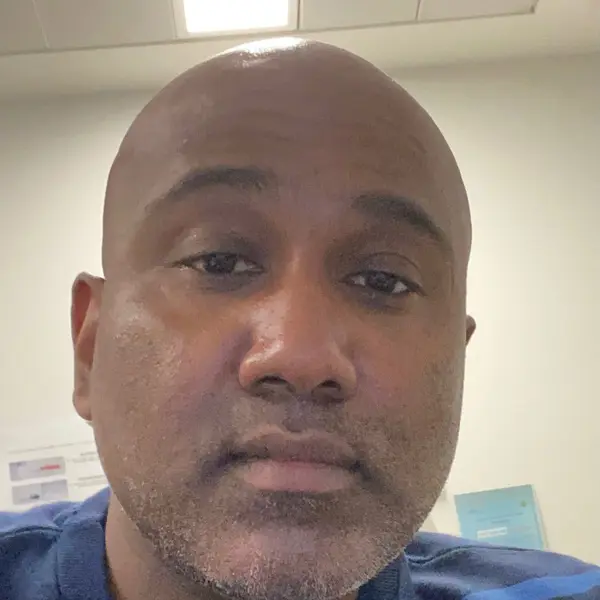

Between sips of inky-black canteen coffee in Gateshead’s QEH (Queen Elizabeth Hospital), GP Paul Evans sums up the polarising feelings which arise just minutes before logging on at midday on a Saturday for yet another OOH (out-of-hours) shift.

‘There’s always a sense of trepidation because you don’t know what the shift is going to bring,’ Dr Evans says. ‘But there’s often something very satisfying about interactions where you can make a quick and obvious difference to a patient right there and then.’

Dr Evans works for the Gatdoc urgent primary care service in Gateshead, which operates from a few consulting rooms at the outpatient department at the QEH. The service has been running since 1994 and relies on local GPs stepping up to take on shifts and support communities when they aren’t able to access mainstream primary care.

This could be the winter that finishes a lot of us in the NHS

GP

The way Dr Evans talks about working in OOH care seems to betray his background of having qualified as a GP in the military.

He worked in the military for 11 years, before taking a salaried post at a practice which was largely responsible for the students at Durham University in the heart of the cathedral city, locuming for a while and then settling at a small practice in deprived central Gateshead, and gives off a sense of being more comfortable in chaos than most – ready to embrace whatever comes next, armed with the expertise and experience to impose himself on stressful situations.

Within seconds of having signed into the system, the patients begin to come thick and fast and Dr Evans deals with each at what seems a remarkable tempo – each question quickly triaging and assessing while fiercely pinpointing where the patient might need to be seen and what steps to take next.

An endless queue

In the space of just eight minutes the first patient – a 52-year-old with incredibly complex medical history, including taking upwards of 40 tablets and drinking a bottle of wine every day, and now presenting with chest pain, lack of feeling in her legs, swelling and breathlessness – has an ambulance arranged and clearly feels understood and reassured.

Dr Evans is ‘greatly concerned’ but has done everything he can – and with real urgency. This area of medicine is marked by sheer variety, but it appears few calls are totally misplaced and most patients need face-to-face follow-ups. All are given times in the coming hours, depending on the level of urgency.

One sounds like a gall-bladder issue and arrives in pain, another is carrying a football injury which needs scans, another requires help dressing a wound. While the nature of the patients’ needs are variable, there is one definitive thread running throughout: there is always someone waiting.

This winter could be spectacularly bleak

GP

Much of Dr Evans’s work in this North East consulting room is reactive – urgent responses to problems that need immediate attention.

Yet, as the patients come and go, it is also hard to avoid a growing sense that many patients might not be here, presenting to a strained OOH service, if things were different in their communities.

Many of Dr Evans’s patients feel like the tragic case studies of a society which has decimated its public health structures, failed to invest in routine general practice and where last-gasp parachutes such as food banks and OOH care are becoming all too routine.

‘The impact of austerity is massively significant,’ Dr Evans, who is also a BMA council member, says. And this winter, with the NHS breaking at the seams, Dr Evans is deeply concerned for his patients and communities. ‘We will see so many excess deaths.’

‘Absolutely shattered’

One North East doctor who was asked to reflect on the situation in his area during the winter told The Doctor: ‘Patients are being treated in virtual wards for which the staff do not exist and they are supposed to get better in their own cold, grotty homes. This winter will be spectacularly bleak.’

In OOH care there is a tangible sense of the fate of doctors and services being at the whims of whatever is going on in the NHS and society. With freezing temperatures, soaring respiratory viruses and an NHS struggling to cope Dr Evans fears the effects of this winter could be catastrophic for the future.

He says: ‘This could be the winter that finishes a lot of us in the NHS – that’s a terrifying prospect. We are working through this winter with none of the “all in it together” spirit that we have had before. People are spent.’

It is no exaggeration. On 18 December, BMA Northern Ireland GPs committee chair Alan Stout tweeted there were nearly 400 calls in Belfast alone to be returned, with just two GPs working OOH. ‘Huge and unsafe pressure,’ he said. Similar warnings can be heard across the UK.

The questions of the sustainability of this situation are pertinent. Dr Evans, to at least some extent, thrives in the pressure and adversity but for most doctors this sort of workload and intensity would be too demanding to be realistic in the long term.

Even Dr Evans, who admits he has an abnormal tolerance for pressure, sometimes goes home after a shift and needs time to reflect and recover, describing himself as ‘absolutely shattered’.

The Doctor received a text in the second week of December that reaffirms the sense of the successes and failures of OOH care being so contingent on the demands elsewhere on the NHS. It says: ‘Never known OOH to be so busy.

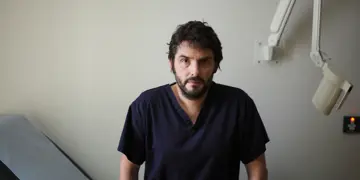

Thirty-five patients when I came in… A&E standing room only.’ The sender, East London GP Selvaseelan Selvarajah, is one of the clinical leads for the OOH service which runs at Homerton hospital.

The most shocking aspect is that Dr Selvarajah’s service is usually able to manage demand well.

When The Doctor visited in November patients were supported quickly and efficiently. There was no sense of this being an NHS in which patients having heart attacks at home were waiting hours for ambulances.

Lack of investment

The driving force behind this demand was an outbreak of Streptococcus A, heavily covered by the media and frightening parents and families across the country. Doctors around England reported huge increases in demand from those who genuinely needed support and a significant influx of people who did not seem equipped to self care with relatively minor viruses.

Dr Selvarajah’s assessment is that this is a health service which has ‘missed the lessons’ of the COVID-19 pandemic. Those failings, he says, are a lack of investment in public health and primary care, national campaigns for parents and better support for schools. He adds: ‘Instead it’s fallen on the NHS to tackle this. So, at a time when we are so busy, this has added to additional pressures.’

In normal times it is a much more calm affair in OOH at Homerton University Hospital. Dr Selvarajah, who is also a BMA council member, describes a local structure and system which is able to function effectively because of mature, long-standing relationships between staff and provider organisations and a strong sense of what local people need running through services.

We’ve never used anything like its capacity… you could easily see 500 patients a day

Dr Wilson

Dr Selvarajah is, however, acutely aware that around the country conditions in OOH care can be much more difficult, it can be incredibly hard to find the doctors to work the necessary shifts and demand from patients in some areas is astronomical.

For Dr Selvarajah a potential answer to the struggles doctors face in OOH care across the country might lie in widescale reform of the system. He would like to see NHS 111 overhauled, with clinical pathways for call handlers removed and 111 integrated into GP OOH hubs, urgent treatment centres, admission avoidance services or others with clinicians supported by call handlers to triage in the first instance, rather than the duplication of triage and assessment that often exists in the system. He describes the way of doing things as ‘splintered’.

Unfulfilled potential

An industrial estate just a few hundred yards from Aston train station in the north-east of central Birmingham might seem a much less likely location for an OOH GP service than the local hospital trust – but among the builders’ merchants and car garages off Lichfield Road that is exactly what can be found.

The facilities here are remarkable – a vast site containing call handlers, doctors and even a drive-through GP surgery with cars parking up outside consultation rooms transformed in a warehouse which seems like a medical McDonald’s.

Here, there is a sense that the system, as it is, is working relatively well in the face of great demand and dwindling resource. But for Fay Wilson, Birmingham GP and medical director of the Badger organisation which runs the centre, there is a sense of frustration and eagerness to do more.

The data shows demand is increasing but Dr Wilson and her colleagues are only funded to provide the level of service they used to in 2016 so can’t hire more staff and widen access.

‘We’ve never used anything like its capacity,’ Dr Wilson says, speaking about the drive-through GP surgery. ‘You could easily see 500 patients a day.’ There are 23 bookings commissioned each day. Dr Wilson confirms that there is the demand in the system to benefit from higher usage but that effectively all of that shortfall is ‘just waiting’ as things stand.

One of Dr Wilson’s visions is that the centre could effectively alleviate a significant amount of pressure on mainstream general practice by being able to see patients who request on-the-day access to primary care 24 hours a day, once built up. As is so often the case, the stumbling block to a potentially transformational project is resource.

Regardless of where you go in the country it seems the uniformity of rocketing demand and pressure on NHS services is matched by the ideas and the appetite among doctors to meet that need and drive change and improvement.

In a recent Daily Mail column denouncing health professionals taking strike action, health secretary Steve Barclay said his priority was patient safety and outlined his appetite to ‘get our NHS back on track’. Perhaps it is time ministers listened to those who know best to do just that.