A digital dawn?

A digital dawn?

Technology has the potential for transformative change but the day-to-day reality can be deeply frustrating. Ben Ireland asks what it will take to produce a successfully digitised NHS at last

Utopian visions of seamless futuristic healthcare imagine slick systems which allow doctors to spend more time with patients and offer increasingly holistic care. It’s a fine theory.

But talk to today’s healthcare professionals and their reality is infuriatingly slow computers, when they don’t crash, often providing incomplete patient data. Doctors can be left sifting through paper-based records to fill gaps. Some question whether technology really helps.

The BMA report Getting IT Right found more than 13.5 million working hours are being lost each year from inadequate IT systems and hardware in England alone, the equivalent of almost 8,000 full-time doctors. In monetary terms, that’s nearly £1bn – or roughly the cost of restoring junior doctors’ pay to 2008 levels.

Previous attempts to digitise the NHS – the world’s largest single set of such personal data – stretch back to New Labour. Various reviews suggesting overhauls have come and gone.

Tomorrow's dream

Yet with COVID lockdowns accelerating the uptake of digital technologies in everyday life for doctors and patients, plus the vaccination rollout leading to 30 million people now using the NHS App, could technology’s day in the NHS have finally arrived? Doctors think so.

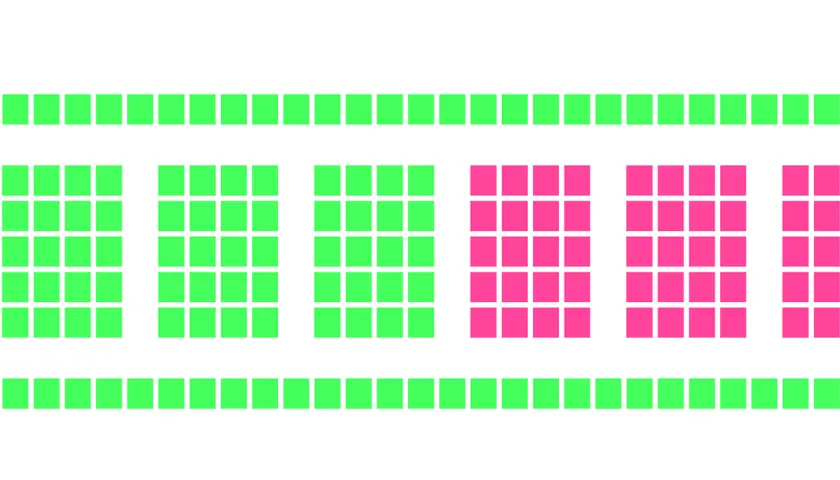

More than 94 per cent of respondents to the BMA’s report agreed IT and digital can help tackle the now 7.1 million record backlog. More than half (57 per cent) believe the effects could be ‘significant’.

The Government agrees and – with a severe shortage of doctors and nurses, who take years to train – had set aside £2.1bn from the now-scrapped health and social care levy for digital transformation.

Prime minister Rishi Sunak (who introduced the levy as chancellor) and current chancellor Jeremy Hunt (the former health secretary) have assured MPs the levy’s repeal will not reduce NHS funding; however, high inflation means budgets will be squeezed in real terms.

Data sharing

Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust was an early adopter of digital advancements and is graded level 7 (the highest) by HIMSS (Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society).

Chief clinical information officer Afzal Chaudhry, a consultant nephrologist, says the problem was identified 12 years ago.

Systems were ‘barely adequate for what we were doing in 2010’ so ‘weren’t going to be adequate for 2015 or 2020’, he says. For Dr Chaudhry, ‘glossy tech’ isn’t the point.

Cambridge focused on making day-to-day workflows more efficient but ‘needed a clear central vision’ for all clinical, reporting and analytical staff. ‘Everybody needed to be part of the transition,’ he says.

The NHS hasn’t invested in tech as it has been seen as risky

Dr Koczan

Convincing them was the hardest step, he recalls. ‘There are hundreds of reasons for not doing something on this scale.

The only way was to build a strong coalition that believes this is the right thing to do.’ One example is Dr Chaudhry’s weekly clinic for 80 patients, which offers test results online.

‘Before, about half of patients would phone the next day. Now, they don’t have to.’ There are also cost and environmental savings. Cambridge sends one million fewer letters and documents per year, saving £165,000 in printing and posting and £288,000 in staff phone call time.

In a 21-month period 296,183 PCR COVID test results went out, more than 19,700 vaccination appointments were booked across the Cambridgeshire & Peterborough ICS (Integrated Care System), estimated to have saved £53,500.

Phil Koczan, London GP and digital clinical champion for primary care digital transformation at NHS England, says changes must come one step at a time. But he believes a giant leap was made during COVID.

‘If you go back four to five years, there was a lot of concern between GPs about sharing data. A lot of those concerns about whether sharing data or not is the right thing to do have gone. Now, it’s not about whether or not we share data but how we do it safely,’ he says.

‘Technology can do a lot more than we use it for. In the past the NHS hasn’t invested in technology as it has been seen as risky, and quite rightly we haven’t pushed the boundaries. What COVID has taught us is we need to maximise clinicians’ time – and make technology as easy as possible to use.’

A major issue the BMA’s report identifies is ‘interoperability’ – how different systems used across primary and secondary care (such as TPP’s SystmOne and EMIS) ‘talk’ to each other. Doctors say they don’t.

Asked for one change they want to see in the next five to 10 years, responses included ‘one IT system for all functions’ and ‘a nationalised NHS IT service accessible by primary and secondary care’.

The Government’s June Data Saves Lives policy paper promises this. It says: ‘We want a world where every person and the health and care professionals involved in their care can draw information from, or put information into, the same shared care record in a safe and straightforward way.’

But records come in different shapes and sizes. SCRs (summary care records), basic patient information created from GP records and readable by authorised staff from NHS 111 to hospital doctors and nurses, are now available nationally.

Their scope was broadened in April 2020 in response to COVID to include more information such as resuscitation preferences and next of kin details. They also changed from opt-in to opt-out, which increased the number of records being accessed from three to four million to about 55 million.

We have gone from not enough information to too much

Claire Lambie

GP Connect allows primary care practices to share SCRs with each other and book appointments for patients. Local agreements for using records for direct care were in place pre-COVID but have been extended nationwide. COVID-enforced changes remain in place until a permanent policy is confirmed.

Primary care networks can also make their own data sharing agreements. ShCRs (shared care records) introduced in April 2021 go further. An evolution of local health and care records, these allow all doctors within an ICS to not just view but add to records. This could be a GP uploading the outcome of a patient’s latest consultation or a hospital doctor sharing blood test or X-ray results.

All ICSs now have a ‘basic shared care record’ in place and the Government has promised all organisations within ICSs will have a ShCR that ‘meets the requirements’ by December 2024.

This could involve social care too. However, ShCRs are not national. So, a clinician treating a patient from Manchester in hospital in Cornwall while on holiday can only access the more basic SCR.

The BMA found 98 per cent of secondary care doctors and 81 per cent of primary care doctors encounter delays accessing data from the other. Only 30 per cent of doctors expect to be able to seamlessly and instantly access patient data in 10 years’ time. Improving interoperability is a ‘high priority’ for 74 per cent of respondents.

'Data overload'

GP Diana Hunter, chair of Cambridgeshire local medical committee, has experienced long delays in receiving records from busy hospitals, citing waits of six to 12 weeks for MRI scans.

She gives the example of a discharge summary she received late one evening when she was new to her surgery: ‘The note said the patient was admitted because her husband was unwell. I knew she hadn’t been on one of the medications for some time, so asked a colleague who told me her husband died two years ago. It was more than two years late.’

Dr Hunter is ‘broadly in favour’ of ShCRs but warns ‘information overload’ may cause delays and risks to patient safety. Systems are ‘only as good as the person putting the information in’, she says, pointing out GPs are the sole data controller in SCRs.

‘I can see the advantages to more people being able to add to the record, but it becomes massive. You risk missing key information within that. Missing things is the main thing we worry about in general practice. When you need information urgently it can make things more challenging.’

Claire Lambie, chief nurse information officer at NHS Gloucestershire CCG (clinical commissioning group), says COVID was ‘an opportunity to challenge the status quo’ on digital technology and wants ‘common sense’ changes to remain in place. But she accepts ‘we have gone from not enough information to too much’.

‘We need to work on data quality and appropriate data quantity. We need to ask ourselves why we are recording it. Is it to help the next clinician, or to prove we have done something? Clinicians on occasions may feel they have to wade through multiple pages to find the specific information they need, which may not even be there.’

Ms Lambie wants to see ReSPECT (recommended summary plan for emergency care and treatment), a record of how a patient would like to be treated in an emergency when they do not have the capacity to express choices, to be digitised and accessible nationwide.

Most trusts have adopted this process, but in paper form or held digitally on local systems, she says. ‘The number of times these are not available when needed is too high,’ she says. ‘As a patient, I would expect that to be known wherever I present in the NHS.’

Chasing easy wins is the way to make tangible progress, says Ms Lambie. ‘Digital transformation has to solve a problem,’ she says. ‘If it’s not broken or can’t be improved, don’t muck about with it – there are plenty of other things that need transformation.’

Dr Koczan believes ‘low-hanging fruit’ comes at a local level. ‘A lot of record sharing is based on trust,’ he says. ‘And 80 to 90 per cent of care exists within the local health economy. Building something national would be nigh-on impossible and take years – but in London we have built a relatively comprehensive system quite quickly because we talk to each other.’

He believes ShCRs’ ‘richer record’ also helps by involving a wider range of clinicians, in areas such as mental health and social care – but accepts the information overload argument. ‘We need to build a bit of intelligence into the system,’ he adds.

Pieces of a puzzle

Dr Koczan envisions a system whereby doctors can check a basic record, but ‘drill down’ into specific data based on what the patient presents with.

‘Say I have a patient with diabetes; what is their blood pressure over time, their blood sugar readings, what medication led to that change? At the moment we only have some of the jigsaw.’

He wants to build on structured records, which are available through GP Connect. The latest data shows that while 107 million read-only records have been viewed, only 2.4 million structured records have. Those are from 70 per cent of GP practices, compared with 99 per cent sharing read-only records.

‘That sort of data is only just coming on board,’ says Dr Koczan. ‘We need to populate these systems. That’s why it’s so important to have standards in place early.’

This feeds back into the interoperability argument for a central IT ‘language’ – or common intermediary – that all systems can ‘talk’ in, allowing different programs to be designed to create specialised patient profiles.

Getting staff involved

One of the BMA report’s recommendations backs up Dr Koczan’s point. It wants the NHS to set standards for suppliers insisting their technology can operate in tandem with other providers’ systems.

Another of the report’s 31 recommendations is improving hardware for doctors, including upgrading inadequate equipment that risks patient safety and not sharing laptops and tablets between too many colleagues.

Clinical leadership and involvement in digital transformation must also be encouraged and ensured, it adds. Only 11 per cent of doctors responding to the BMA report say they always have the necessary equipment for their role – and just 4 per cent believe software is completely fit for purpose.

Dr Chaudhry feels staff need to be encouraged when trusts take the digital plunge. ‘For some, change might seem insurmountable,’ he admits. ‘Some might even leave because they don’t want to face it. We don’t want to leave anybody behind but, equally, nobody gets to hold us to ransom.

'You can’t fail to grow and mature the needs of a department because one group doesn’t want to move forward.’ On the other hand, he accepts: ‘You can have the best technology in the world but if your staff don’t want to use it, or it doesn’t fit with what you want to do, you won’t reap the benefits.’

Castles made of sand

Dr Chaudhry recalls Cambridge’s ‘difficult first year’ of transition in 2014. ‘It was turbulent because we were changing so much,’ he says. ‘There were [negative] articles in the press.’

But he is adamant: ‘If you work on it you can come out of that and end up much stronger.’

In terms of system breakdowns, there has been ‘one major episode’ in the last eight years at Cambridge, he says.

To avoid such instances, he suggests: ‘Don’t build your house on sand. If the infrastructure is flawed, you’re going to have problems.’

Digital transformation is a never-ending journey

Dr Koczan

Over time, Cambridge has become ‘more and more digitally mature’, Dr Chaudhry says.

But he caveats there is ‘no end point’ for digital transformation, but ‘a continuous upward spiral of incredibly high-quality care underpinned by digital’.

He believes there has been ‘a lot more learning across the entire NHS’ than when Cambridge took the digital leap, which means trusts can see what comparable organisations have done to ‘determine their opportunities’.

Dr Chaudhry compares technology’s continuous evolution with medical progress: ‘Treatments change, things we used to do as major open operations are now in-clinic procedures.’

So for technology, such as medicine: ‘The journey stretches out into the future. In a way, that’s what hospitals always have been.’

As Dr Koczan puts it, digital transformation is a ‘never-ending journey’.

- Until September 2024, resident doctors were referred to as ‘junior doctors’ by the BMA. Articles written prior to this date reflect the terminology then in use