The price of a drink

The price of a drink

Northern Ireland may be the next UK country to set a minimum unit price for alcohol - a measure which has been shown to save lives and reduce harm. Jennifer Trueland reports

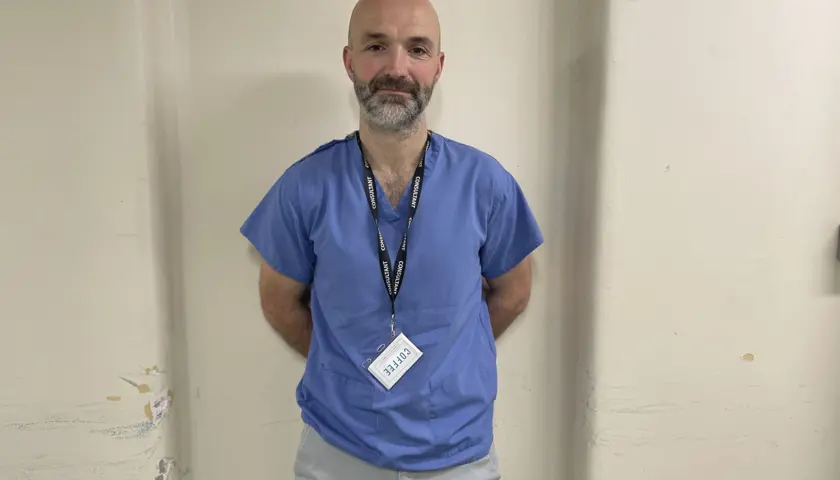

Working in the liver unit at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast, consultant hepatologist Roger McCorry sees the effects of Northern Ireland’s alcohol problem every day. And sometimes it can be heartbreaking.

‘There’s a girl we’ve been seeing a lot of, who started drinking at 14, and has been drinking a bottle of spirits a day for the last 10 years. There’s a background of trauma and abuse, and her father spent a lot of time in prison. She’s now socially isolated from her family and has basically lost everything.

At 25, she’s got end-stage liver disease, and we try to manage the complications of that, but each time she’s discharged she relapses back to alcohol. It feels hopeless, and absolutely tragic, because this is a life lost.’

Northern Ireland looks likely to be the next country in the UK to introduce an MUP (minimum unit price) for alcohol. Health minister Mike Nesbitt has stressed his commitment to the move, and campaigners – including the BMA – are enthusiastic.

MUP was implemented in Scotland in 2018 (after years of vicious fightback from the alcohol industry). According to SHAAP (Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems), MUP reduced alcohol consumption by 3 per cent in the three years after implementation, with people who bought the most alcohol before MUP reducing their purchasing the most. MUP also reduced deaths directly caused by alcohol consumption by an estimated 13.4 per cent, equivalent to 154 fewer deaths per year, and reduced hospital admissions by an estimated 4.1 per cent.

Elsewhere, Wales introduced MUP in March 2020, meaning that if Mr Nesbitt gets his way, England will be the only part of the UK without it.

Saving lives

Research suggests that if Northern Ireland does go ahead, it would prevent 29 alcohol-attributed deaths annually and save health services some £2.2m per year by reducing hospital admissions.

For those working on the front line, it can’t come soon enough. This includes Dr McCorry. In his service – which is the regional liver unit – about half of workload is alcohol-related liver disease. Typically, the age range is early 30s through to patients in their 60s, and there’s a growing proportion of women. Many die young.

‘The striking thing about patients with alcohol-related liver cirrhosis is that they tend to die 20 or 30 years younger than their peers with respiratory and cardiovascular conditions, so the mortality rate is high, and we see folk dying in their 40s and 50s, which you don’t tend to see in other specialties.’

While alcohol-related problems are doubtlessly multi-factorial, with poverty, social circumstances and intergenerational issues all playing a part, Northern Ireland’s recent history is also a component, says Dr McCorry.

‘There’s definitely a legacy from The Troubles. A lot of our patients have PTSD. Many of them will have had some sort of involvement in paramilitarism, or they were caught up in a traumatic event. Alcohol has become a coping mechanism for them.’

Alcohol-related morbidity impacts on every specialty in our hospital

Roger McCorry

MUP would not solve every problem, he concedes, but it would help. ‘We know that 80 per cent of alcohol is consumed by 20 per cent of drinkers, and there’s no doubt about it that, based on the Scottish data, MUP would transform the way that many of these patients consume alcohol – in Scotland, for instance, it’s largely wiped out the white cider industry.

‘We’re mindful of the fact that it’s not going to stop patients drinking, but my hope is that there will be harm reduction, because instead of consuming 200 units a week, it’s reduced to 100 units a week. That might not seem particularly significant, but there’s no doubt there will be harm reduction with that, and perhaps as a result, the patient will be less likely to present at the emergency department or seek admission in a health crisis.’

He also hopes MUP would prevent a large cohort of patients from developing the sorts of drinking patterns at an early age that would lead to life-long chronic problems. And, certainly, the stakes are high. Dr McCorry describes his patients as biologically a lot older than their chronological age. Heavy alcohol consumption tends to go hand-in-hand with poor nutrition, and many will be undernourished and deconditioned before a crisis brings them to hospital – requiring a multidisciplinary approach to get them well.

‘Alcohol-related morbidity impacts on every specialty in our hospital, and in my view, everyone should have a responsibility to try to identify these patients and get them to appropriate support.’

That’s not to say MUP would have an impact on all patients with potential or actual liver problems.

‘We see a lot of people who would be horrified if you labelled them an alcoholic. They’ve just got in that bad habit of drinking a bottle of wine every night after work, and they’re often highly functioning. MUP probably won’t address their issues, but it’s much more likely to address the drinking issues in chaotic individuals who are often socially isolated, often homeless, and who are drinking industrial levels of alcohol, as opposed to those more stable folk for whom it’s just part of their routine.’

Just down the road in his practice off the Falls Road, Belfast GP Michael McKenna is starting his morning surgery. Already, he explains, checking blood results before appointments begin for the day, he has spotted worrying signs of liver disease in two young patients – enough to spark a referral for further investigation. This is sadly typical for his patient group in this relatively deprived part of town.

He would love to see an MUP for alcohol implemented in Northern Ireland, although he knows it isn’t a silver bullet. ‘It’s a start,’ he says simply. ‘It’s never going to address the problem completely, there will always be alcohol addiction, but what you’re doing is taking off the top end of that harm, and you’re reducing attendance at hospital and admissions for alcohol-related harms.’

Dr McKenna, who is a member of the BMA Northern Ireland GPs committee, looks at Scotland, where he lived and worked before moving back to his native Northern Ireland, and is impressed with the impact of MUP. ‘Scotland is starting to see the benefits – they’re seeing real reductions in the number of presentations to hospital for liver failure. The youngest patient I have with fibrosis is 27 – she drinks three bottles of wine a day, the cheapest wine possible. It’s like the Frosty Jack scenario [referring to a brand of cheap cider] – you can get a large bottle of Frosty Jack for four or five quid. And there’s an awful lot of alcohol in that.’

He is not wrong. In an off-licence just a few hundred feet from his surgery, there are rows upon rows of huge bottles of cheap white cider. In this particular shop, a 2.5 litre bottle costs £7.50. According to the label, it’s suitable for vegetarians, vegans and coeliacs – and, at 7.5% proof, contains 18.8 units of alcohol. In Scotland, with MUP set at 65p per unit, the same ‘hit’ would cost a minimum of £12.22.

'A necessary step'

MUP is ‘straightforward harm reduction’, Dr McKenna says, because if people can’t afford to buy more alcohol, they make what they can afford last longer. Although poverty might not be the only driver towards alcohol misuse, it plays a role, so price is important. ‘Addiction crosses all boundaries and liver disease is impacting more and more on all parts of society, but it is particularly bad because of the access to high volume alcohol with lots of units,’ he says. ‘In terms of simple harm reduction, I do see MUP as a very necessary step.’

The good news is that the health minister agrees. A spokesperson for the health department told The Doctor that – all being well – the necessary legislation will be laid during the current Northern Ireland assembly term.

‘Some of the biggest health inequality gaps in Northern Ireland relate to alcohol misuse, with alcohol related deaths almost four times higher in the most deprived areas compared with the least deprived areas,’ the spokesperson said.

‘The wider evidence base demonstrates that MUP is a targeted and proportionate approach to address this issue since, under the policy, the stronger a drink is the higher the price below which it cannot be sold. This is important as those who drink at harmful levels tend to drink the strongest, cheapest drinks.

‘Proposals for legislation on MUP will only progress with executive approval and subsequent Assembly debate and scrutiny. The minister has been and will continue to engage widely with his ministerial colleagues to progress this important matter. Subject to executive approval, the department would hope to progress the necessary primary legislation within the current Northern Ireland assembly mandate.’