The ordeal: doctors reflect on the COVID crisis

The ordeal: doctors reflect on the COVID crisis

Bungled guidance, a ‘criminal’ lack of protection for staff, and patients ‘raining from the sky’. As a new phase of the COVID inquiry gets under way, three doctors describe their experience of the pandemic

Emergency medicine doctor Saleyha Ahsan was seconded into ITU during the height of the COVID pandemic, working in a ‘relentless’ environment as wave after wave of patients arrived in a ‘tsunami of horror’.

When her father, 81, caught COVID, Dr Ahsan (pictured above) returned to London from her job in north Wales to care for him. He died a week later and within a month she was back on the front line caring for others’ family members.

This dual view of the biggest global health crisis in living memory puts Dr Ahsan in as strong a position as any to comment on the lessons that could, or should, be learned from COVID.

She spoke to The Doctor as module 3 of the UK COVID-19 Inquiry, which is examining the effect on healthcare workers, their patients and the systems they worked in, got under way.

Dr Ahsan’s reflections give a sense of how healthcare professionals, applauded from lockdown doorsteps as they risked their lives to save others, felt isolated from and betrayed by the Government of the time.

‘I remember feeling utterly disgusted that there was nothing at a high level that had been done to prepare us to be able to manage this,’ Dr Ahsan says as she recalls when it became apparent COVID was inevitably arriving on UK shores.

‘Information and messaging was changing on an almost daily basis, which left everyone confused.’

PPE downgraded

At the emergency department in Dr Ahsan’s trust, guidance ahead of the first UK lockdown in March 2020 was for staff to wear full PPE (personal protective equipment), including FFP3 masks, surgical gowns and eye protection. But: ‘The same week, the advice coming through changed about three times. Each change meant something being taken away from our PPE. By the end of the week, it was just a white apron and a surgical mask.

‘There was a message, internally, that suggested we weren’t allowed to ask any more questions about it, and if you did you could potentially be disciplined.

‘Each change cited the same evidence, research on flu. I kept thinking, “Where’s the evidence for downgrading?” Everything was coming from central government. But there was no central plan. The people employed to create those systems, paid vast sums of money, failed.’

Dr Ahsan describes how consultants at her hospital, and across the country, were left to re-configure clinical spaces to cope with the highly infectious and often lethal virus and ‘there appeared to be no central government leadership on this’.

‘You were thinking that at any point you could get sick,’ recalls Dr Ahsan, who caught COVID herself during the first wave.

‘You felt vulnerable, very frustrated, disgustingly grubby all the time.’

‘I was worried about my family in London. I was worried about my dad, and I was worried about my other siblings because they are doctors as well. I was worried about my brother, a doctor who is immunocompromised caring for these patients without adequate PPE. I remember thinking “How many of us are going to come out of this alive?”.’

Dr Ahsan also remembers feeling uneasy with early advice to the public that dismissed the effectiveness of wearing face masks to contain the virus.

She felt ‘utterly repulsed’ by comments from the then deputy chief medical officer Jenny Harries about wearing masks without the explicit advice of a medical professional being ‘a bad idea’ because of a risk of contamination.

Bungled messaging

Dr Ahsan also recalls ‘strict management’ insisting patients who were due to be discharged to care homes were not swabbed.

‘There were some really hard conversations,’ she says. ‘Nursing staff were following that instruction even if they didn’t like it. Some care home managers were begging. But it was so heavily policed.

‘I’ve never seen such micro-observations of how we were doing things, and that wasn’t just at my hospital. It was everything, from the way people were wearing PPE, the way we were discharging patients, how we created more capacity.’

The bungled, top-down messaging to healthcare workers, and the public, as well as decisions to go ahead with large events such as the Cheltenham Festival horse-racing meet, ‘all contributed to this tsunami of patients coming into hospitals’, says Dr Ahsan.

I remember feeling utterly disgusted that there was nothing at a high level that had been done to prepare us to be able to manage this

Dr Ahsan

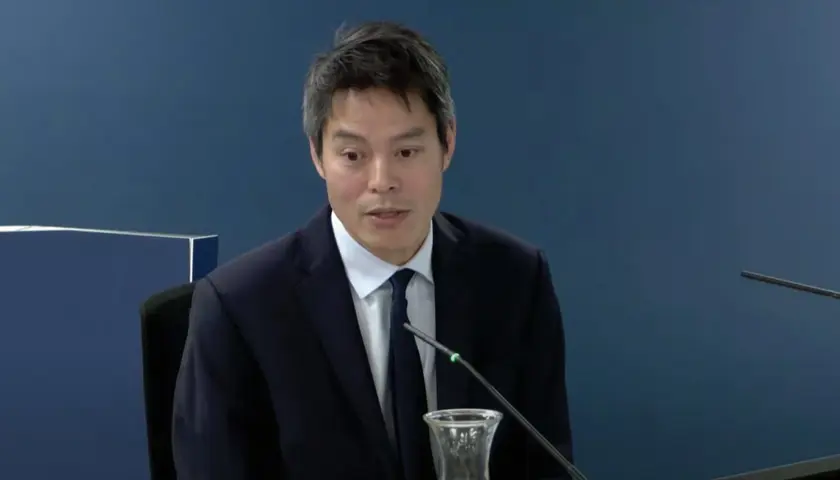

London consultant anaesthetist Kevin Fong, who gave evidence to the module 3 hearings, equated the height of the pandemic to facing ‘a terrorist attack every day’ with patients ‘raining from the sky’.

Dr Fong, who worked during the 7/7 London terror attacks, said some hospitals were ‘bursting at the seams’ and were close to ‘a state of collapse’ in the early waves of COVID, with ‘traumatised’ staff reluctantly putting deceased patients in clear plastic sacks using cable ties because they had run out of body bags.

‘These people are used to seeing death, but not on that scale, and not like that,’ he told the inquiry. ‘Whatever the figures show you the experience for them was indescribable. It really was like nothing else I have ever seen, and certainly not like [anything] else those teams have ever seen.’

London GP Tilna Tilakkumar was a junior doctor (now known as a resident doctor) during COVID. She was recalled from a community mental health rotation to her home trust in March 2020 after an outbreak on an inpatient ward for patients with complex mental health needs.

Within a week, she was left as the only doctor on the ward owing to other doctors’ illness, with only a ‘skeletal team’ because other staff had contracted COVID.

‘It was really just trying to organise chaos,’ she told the inquiry, noting how there was one observations machine for 26 patients. Attempts to isolate patients were ‘impossible’ and she relied on ‘word of mouth from colleagues’ for how to treat COVID patients because of a lack of top-down guidance.

Dr Tilakkumar described how PPE guidance was ‘downgraded’ within her first week on the inpatient ward, from full PPE at all times to only ‘when in contact’ with COVID patients.

This was despite treating patients who could become ‘very agitated’, ‘couldn’t be kept in their room,’ would ‘never wear a face mask’ and may also spit.

‘The entire ward was a COVID ward as far as we were concerned,’ she told the hearing. ‘PPE should have been worn at all times.’

Unsafe equipment

Some staff members ‘bought visors and goggles off the internet’ and others continued to wear PPE at all times against trust rules out of fear for their own safety. Dr Tilakkumar described how a visiting manager saw a healthcare assistant wearing a plastic apron, and ‘pulled it off her’.

Dr Tilakkumar had been asking for FFP3 masks for her team but was told they were only necessary in aerosol-generating procedures. She described how the wrong masks were brought to fit tests on her ward.

Testing for staff was only permitted if they had symptoms, and only 35 tests were available per day across the entire trust. Dr Tilakkumar never had an antigen test while on the ward, but in May 2020 – after leaving the ward – tested positive for COVID antibodies.

Dr Ahsan describes how staff at her hospital were left wearing out-of-date PPE with ‘masks breaking off our faces while we were in the red zone trying to deal with very sick COVID patients’.

‘We were always up against it, dangerously so. It was not only the lives of our patients, but the lives of our colleagues at stake because of the significant systems failings.’

Staff also went to extreme measures to protect their families by isolating from them. ‘I had colleagues who were living in tents in the garden,’ she shares.

Dr Tilakkumar requested to be put up in hotel accommodation with her husband, who was working in the emergency department, to protect her parents who they were living with. This request was accepted, but the space was ‘very basic’ and ‘definitely not meant for long-term living’.

Dr Ahsan says the lack of protection given to healthcare staff during the peak of the COVID pandemic is an ‘injustice’ and ‘feels criminal because it was so avoidable’.

‘The moral injury continues to this day because there has been no accountability,’ she says.

Personal loss

Dr Ahsan’s personal loss came in late December 2020, when her father Ahsan-Ul-Haq Chaudry contracted COVID as the Alpha variant took hold – on the date of the now infamous Downing Street press conference rehearsal for how to deal with questions about parties.

‘They eventually locked down, but by that point numbers had already started to spike,’ she recalls of the period when it later became apparent that Downing Street staff were holding parties. ‘Everyone was sick and coming into hospital. The numbers were horrendous. I saw that from the perspective of the public with a sick loved one.

‘I looked after my dad in hospital, I stayed with him 24/7. The hospital allowed it because my dad had existing care at home, but I think also because they were just so overwhelmed. The situation was so desperate, everyone had COVID.

‘Bearing in mind I’d seen it all working in ITU, looking after my dad was the most frightening thing. He was 81, but a good 81. He just deteriorated. The way it killed him was so horrendous, and so avoidable if we’d locked down properly and on time. I still get flashbacks of my distressed father, fighting to breathe. I can still hear his words “I want to die” said through the muffle of a CPAP mask.

It was not only the lives of our patients, but the lives of our colleagues at stake because of the significant systems failings

Dr Ahsan

‘Three days after he died, I had a call from the GP offering him a vaccine. That was pretty painful. That happened to so many people, then to go back to carry on working in it two or three weeks later was really quite painful.’

Dr Ahsan felt so strongly that what she was witnessing ‘needs to be seen’ that she continued to film her observational Channel 4 Dispatches documentary, even when her father was dying. ‘I was driven by that because of the power of the testimony. I had to collect this as evidence.’

Dr Ahsan’s experiences have had a ‘huge impact’ on her career since she last worked in acute settings in March 2021, she tells The Doctor.

‘I haven’t been able to fully work in that space again yet,’ she says. ‘It’s really impacted my progression through medicine. I have to go back, I don’t want to stop being an [emergency department] doctor, but I’ve allowed myself some time to recover.’

As well as making films, and other roles in medicine, Dr Ahsan has embarked on a PhD at the University of Cambridge looking into the effects of attacks against healthcare in armed conflict. She is also an active member of the COVID-19 Bereaved Families for Justice UK campaign group which, along with the BMA, is a core participant in the public inquiry.

Burnout and depression

Many doctors have seen their careers and mental health severely affected by COVID.

Dr Tilakkumar described to the inquiry how – on return to her community placement, and on rotations in obstetrics and gynaecology and general practice – she felt the care given was limited because it was so remote.

She told the hearing she has had two episodes of depression since her experiences in 2020.

‘I didn’t have any problems with my mental health before the pandemic,’ she explained. ‘[It’s] mostly from working in isolation, feeling burnt out and feeling a lack of satisfaction in my work. I don’t feel I can really help patients in the NHS these days.’

The moral injury continues to this day because there has been no accountability

Dr Ahsan

Dr Ahsan has been diagnosed with lupus, a chronic lifelong autoimmune disease, which some studies have shown can be brought on by COVID. For her, life is also different now to how it was before the pandemic.

‘I have my pre-COVID life, my during COVID life and my post-COVID life,’ she says.

‘Life used to feel more optimistic. Maybe there was some ignorance of not knowing our government systems were not robust, and thinking we’ll be looked after at times of national crisis, but it’s almost as though our innocence has been removed.

'It probably is PTSD, something psychological that we need to heal from. It’s made me feel very cynical about the world and the way things are run.

You saw incredible things, people working under enormous pressure. That’s why it was so awful to see the previous Government start to attack and berate doctors

Dr Ahsan

‘On the other hand, I’m overwhelmed by how many good people there are – in terms of healthcare, who have worked above and beyond driven by a goal to save lives.

‘You saw incredible things, people working under enormous pressure. That’s why it was so awful to see the previous Government start to attack and berate doctors, and not respect and acknowledge the sacrifices that were made.

‘Since COVID it has been really relentless, and it is hard work. It gets to the point of self-preservation. You don’t want to make yourself ill by staying in the system for a life of just burnout and betrayal.’

At least 49 UK doctors are known to have lost their lives to COVID, having toiled selflessly for their patients in the face of the pandemic.

As the BMA put it in its opening statement to module 3: ‘The pandemic has had an enormous, and in some cases devastating, impact on those working in health services, on patients, and on the healthcare systems themselves. Behind every statistic is a human story, and a deeply personal experience.’

(picture credit for main image: Getty)

- Until September 2024, resident doctors were referred to as ‘junior doctors’ by the BMA. Articles written prior to this date reflect the terminology then in use