Skills for the frontline

Skills for the frontline

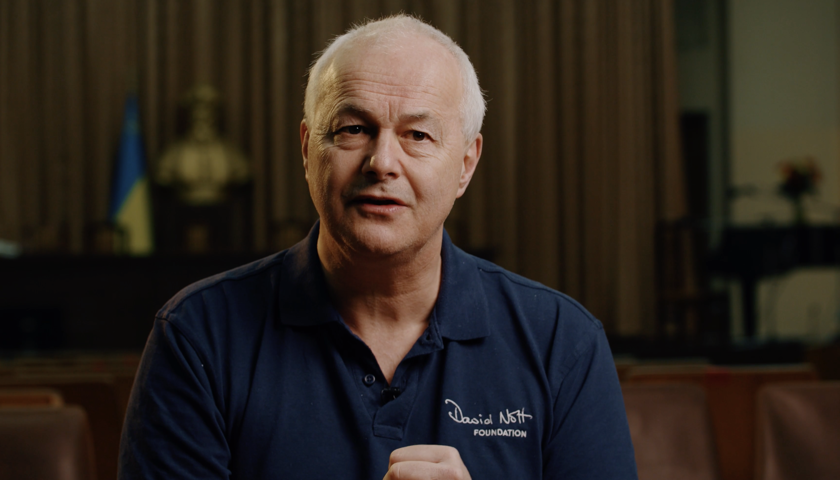

Anaesthetist Ian Nesbitt tells Jennifer Trueland about his work in giving vital skills to doctors in Ukraine and other conflict areas

Ian Nesbitt has a long pedigree in combat medicine. As a reserve forces doctor in the then Territorial Army for 22 years, he served in many countries including Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan.

More recently he has been working with the David Nott Foundation as head of faculty for anaesthesia, helping to expand the organisation’s traditional work in training surgeons in conflict environments to include anaesthetists and other members of the theatre team.

He has just returned from Lviv in Ukraine, where, amid intensifying Russian attacks and rising political temperatures, the David Nott Foundation was delivering bespoke training to medics working on the front line.

The foundation has been working in Ukraine since late 2022, helping to skill the medical workforce up to work in war conditions. Dr Nesbitt has been there several times since his first visit in 2023, including in March. And the difference he has seen witnessed since the war began has been immense.

‘We’ve seen enormous skill acquisition and changes in how Ukrainian anaesthetists and surgeons work,’ he says. ‘When we first started talking to Ukrainian anaesthetists, we would talk about surgical airways and their response was “well that’s an ENT surgeon’s job”.

‘And when we talked about chest drains, they’d say “that’s a surgical skill we don’t have any involvement in”. And we’d talk to them about ketamine as a drug for use in trauma surgery and they had very little experience of it.

Whereas now when we go all anaesthetists expect to be doing surgical airways – and most of them have done. Most of them expect to be doing chest drains, and have done chest drains, and they are very well-versed in the use of ketamine.

‘So, the content of the educational course is updated before every time we go. We keep in touch with Ukrainian doctors and hear what their pressing issues are, and what they want to hear about.’

It's remarkable what the anaesthesia workforce is achieving in Ukraine, he adds, particularly given the lack of resources (not just because of the war, but because it is a low to middle income country which also constrains what they can do).

‘They obviously can’t do everything we can do [in the UK] with all the resources we have to hand. But they test and adjust what they’re doing very rapidly and it’s a big challenge to try and keep up with the advances they’re making because they see an enormous number of war casualties.’

It's a big challenge to try and keep up with the advances they're making because they see an enormous number of war casualties

Ian Nesbitt

Over the last few months, The Doctor magazine has interviewed several UK-based doctors who divide their time between the NHS and humanitarian work. Without exception, it’s been clear that something drives them to want to make a difference, despite the great personal risks they are taking.

Dr Nesbitt, a consultant in anaesthesia and intensive care at the Freeman Hospital in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, is no exception. Asked if he had ever felt his life was in danger, he replies thoughtfully with an incredible sense of perspective.

On deployments with the reserves, he says, he worked in different roles and conditions, including the medical emergency response team. This is, he explains a helicopter-based asset that would pick people up from the battlefield and treat them on the way back to the camp, an emergency unit – essentially some tents where people would receive urgent surgery before being transferred on to more robust, established medical facilities. He also worked in these facilities.

Each carried its own risks. ‘Quite often you’d have holes in the helicopter at the end of the day that weren’t there at the start,’ he says. ‘The period when I was in Afghanistan, some of the insurgents were trying very hard to shoot down helicopters, so that was probably the most risky part of the job. But in Iraq, we had some American “friendly fire” directed towards us, and there was mortaring at a distance.

'So yes, I’ve had some exposure to personal threat but in the grand scheme of things, it’s far, far less than the average infantry man would undergo in the course of a normal day. So, you’ve got to keep it in perspective – and I’ve sometimes felt more at threat cycling in British traffic than I ever felt in Kosovo, say, or Iraq.’

Surgeons supported

After leaving the army, Dr Nesbitt continued doing some humanitarian work, including trying to improve training for anaesthetists – which brought him into contact with war surgeon David Nott, who was looking to expand hostile environment training beyond surgeons.

This is important, says Dr Nesbitt, because surgeons aren’t the only people involved in surgeries. ‘There’s an old adage, popular in anaesthesia circles, that a good surgeon deserves a good anaesthetist, and a bad one needs one,’ he says wryly.

‘I think good surgeons themselves recognise that if you do complicated surgery at the edge of survival, the operation itself is only part of what’s important to the patient.

'If you want to have a surviving patient who goes back to good function, then an awful lot depends on the anaesthesia, on the theatre nursing staff, on the critical care support, or your ability to transfer patients back to somewhere more capable.

'It also depends on the wider system – can you get blood in place? Can you do certain procedures with the right equipment in the right place at the right time?’

Spreading expertise

It's about having a broader understanding of what it takes to get good outcomes, he adds, not just for individuals, but for populations.

‘The David Nott Foundation is starting to broaden its focus from simply teaching surgeons specific skills – it’s teaching healthcare systems how to leverage what they’ve got in the most efficient way.’

Dr Nesbitt is now anaesthesia lead with the David Nott Foundation, training anaesthetists primarily in Ukraine. It’s also being rolled out to other hostile environments including Gaza, Syria and potentially Sub-Saharan Africa.

Depending on the needs of each location, the foundation is teaching ‘hostile environment’ anaesthesia skills to a mix of doctors and other professionals, including technicians and nurses. But essentially, it’s about teaching people to make the best of the resources they have in frequently harrowing circumstances, as well as how to manage people with injuries they might not come across elsewhere.

‘The sad fact of a lot of humanitarian work is that it’s required in areas of conflict, so quite a lot of the case mix will be injuries caused by military type weapons,’ he says. ‘And the wounds caused by military weapons are quite different to what you would see in a civilian society. Even in somewhere with a high prevalence of gun violence, such as America, isn’t completely reflective of what you’d see in a war zone or war-torn area like much of Sub-Saharan Africa, or Gaza, or Ukraine. These injuries are different in their nature and that has an impact on how you treat them.’

It's also about identifying people in the countries where the training is delivered as potential instructors, building capacity and allowing them to run courses themselves. This is an important part of the foundation’s work, he says.

One Ukrainian doctor who is already running training is Uliana Kaschii, an anaesthetist, originally from Mariupol. She credits the training with giving her back her ‘motivation’ after she experienced burnout owing to exhaustion and stress.

‘The first day I came here [to the hostile environment surgical training] I got this motivation for medicine again,’ the foundation quotes her as saying. ‘Yesterday I agreed to go to the front line again.’

When he was in Ukraine in March Dr Nesbitt found the Ukrainian medics were much more upbeat than he had anticipated, given the political situation and the role of US president Donald Trump in trying to force a cease fire on his terms.

The first day I came to the hostile environment surgical training I got this motivation for medicine again

Uliana Kaschii

‘My take-home message from the Ukrainians is that they definitely don’t want war, they want peace. They are sick and tired of the war but they’re absolutely not going to give up, because they recognise that their only way out of this is to keep fighting to get a just peace and a lasting peace. Anything that forces them into a subordinate position is essentially just a pause for the Russians to rebuild, regroup and attack again. They do recognise that this war is going to drag on for some time, but they’re not going to accept a “peace” that would be bad for them and bad for Europe as well.’

As for his own role in supporting doctors in Ukraine, or others of the world’s trouble spots, he contends that his personal motives are actually quite selfish.

‘You get to go to places you'd never get to see otherwise, you meet a variety of really interesting people who are living lives that you could very easily never have any insight into. So, you know, there's definitely an element of selfishness that allows or that helps to facilitate this kind of thing,’ he says.

It also helps him to feel he is making a real difference. ‘Improving other people's lives, I think, is actually quite a significant part of it. When you're working in the NHS, it's quite easy to feel that you're not really making very much difference because you're such a tiny little cog in such an enormous machine that whether you're there or not sometimes is almost irrelevant. In the course of my anaesthetic career in the UK, I guess I’ve anaesthetised tens of thousands of people.

‘But that's a drop in the ocean compared with the potential for training other people around the world, and then they can each anaesthetise tens of thousands of people safer and better and more efficiently and with better outcomes than they otherwise would. I believe in the philosophy of improving the sum of human happiness and I guess this is one way to at least make myself feel that I'm helping to improve the sum of human happiness.’

(Image credits: Getty and The David Nott Foundation)