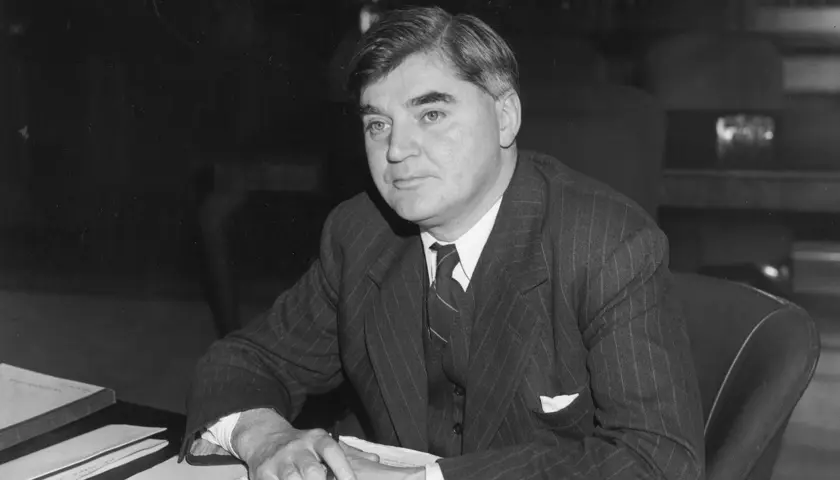

Nye’s lost legacy

Nye’s lost legacy

Nye Bevan is said to have wanted a comprehensive occupational health service, but it never happened, leaving many in smaller companies or precarious jobs without access to this day. Might that finally be about to change?

Occupational medicine was at the very heart of the inspiration for a national health service, but somehow it has been left behind.

Legend has it that Labour politician Nye Bevan partly based his model of an NHS on the Tredegar Workmen’s Medical Aid Society, a scheme providing free healthcare to workers in his hometown – yet occupational medicine was not part of the eventual blueprint.

Now the BMA and other campaigners are fighting to rectify that omission and, some 76 years after the NHS was founded, are endeavouring to give occupational medicine a far greater role in promoting healthier communities in the workplace and beyond.

‘It’s not one of the core NHS services, which I think is really weird,’ says Kathryn McKinnon, who chairs the BMA occupational medicine committee. ‘I’m not saying that occupational medicine is the granddaddy of the NHS, but part of what drove Nye Bevan back in the 1940s to think of providing universal access to healthcare, free at the point of delivery, were coal miners. Welsh pits would have pit doctors. Those populations which had pit doctors – who would also look after the families – had better health than those who had to self-fund access to GPs.

‘That was one of the drivers, so the fact that – in part – occupational medicine triggered or was part of the thought process that resulted in the NHS, [but] was then not included as a core part of the NHS, is enormously regrettable.’

Pilot schemes

At last year’s BMA annual representative meeting, representatives backed a call for a universal system for occupational medicine in the UK in the NHS. Before the general election was announced, it looked like this might have been the direction of travel for the Government, too.

In May, the departments for work and pensions and health and social care announced a £64m pledge ‘to help people stay in work’ and said there would be 15 ‘Work Well’ pilots across England to deliver joined-up work and health support. This followed an announcement on welfare reforms from the then prime minister Rishi Sunak, whose plans to ‘modernise’ the benefits system included a review of fit notes to prevent people falling out of work and on to long-term sickness benefits. Other steps include the appointment of Shriti Pattani OBE as national clinical expert in occupational medicine for NHS England.

A national occupational health service is long overdue, says Dr McKinnon, who is a consultant in occupational medicine and director of medical education at Health Partners Group.

There is a very clear value proposition for occupational medicine

services

Dr McKinnon

‘It remains the case that it’s not the job of the NHS to provide occupational medicine as a specialty,’ she says. ‘It’s down to the employer to provide access to these services. If you work in the NHS, you will certainly have access to it, but only about 50 per cent of the working population of the UK have recourse to specialist occupational medicine services, which is a shame, because we’re very good at what we do.’

Investment in occupational medicine more than pays for itself, she says, in terms of reduced sickness absence, increased productivity and reduced staff turnover. ‘If you’ve got precious, scarce skilled resources, but they just happen to be packaged with an individual who has got some health issues, if the individual is lost to the workforce, those skills are lost to the workforce.’

The case is even more compelling because we have an ageing workforce and people are developing multi-morbidities at a younger age, she adds. ‘The likelihood of those skills being lost to the UK workforce is increasing, so there is a very clear value proposition for occupational medicine services. It is just that it is up to the employer to fund it because there is no universal access through the NHS or another statutory body.’

Universal access call

The BMA would like to see all workers in the UK – including those seeking work, and those who aren’t in work because of a health issue – having access to specialist occupational medicine services. This includes preventive services as well as assessment and support for people who already have a health issue.

‘What has been suggested [by the UK Government] is a great step forward, but it is not really what the BMA has been advocating for a long time, which is universal access to a comprehensive occupational medicine service for all of the UK workforce.’

There is a ‘dearth of detail’ in the pilot plans, she says – for example, it is not clear who will deliver the services, and who will be eligible.

The SOM (Society of Occupational Medicine), which supports occupational health and wellbeing professionals, including doctors, is also calling for a national occupational health strategy, which would include universal access to occupational health. SOM chief executive Nick Pahl says this would boost the economy by reducing the number of people not at work owing to ill health.

‘We’ve been talking to the Treasury and have shared our proposals with them, and also with [chief medical officer for England] Chris Whitty and advisers in Number 10 [Downing Street]. I think there has been real interest in our proposals, which are all costed out, but the problem is that this issue sits across a number of government departments, including health, DWP [Department of Work and Pensions] and business, so sometimes there is a struggle for the issue to be driven by ministers.’

He worries that the general election has slowed a growing ‘head of steam’ in favour of occupational medicine, but the society continues campaigning in the hopes that the new government will give it priority.

Future hopes

Under the SOM’s plan, larger companies would invest in their own occupational health schemes, while the national service would be there for everyone else. At the very least, the society would like to see an occupational health consultant in each ICS (integrated care system) in England and equivalents in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales.

He is confident the workforce will be there to deliver it, although he accepts there need to be more training places for doctors to specialise in occupational medicine and investment in training more generally.

It’s not one of the core NHS services, which I think is really weird

Dr McKinnon

While he welcomes the success of the England-based Work Well plan, he believes it doesn’t go far enough. ‘You need it to be bottom up and top down – you do need that national clinical director, and you need a delivery model that ICSs and health boards will pick up on. Work Well is a start, but from our perspective, it doesn’t have that clinical governance robustness and occupational medicine wraparound for people to feel that it is a clinically secure service.’

With growing numbers of people out of the workforce and the cost of disability benefits increasing, the cost to the economy more widely is significant, he adds. ‘Any government will have to take that seriously. With the election, you might lose a bit of momentum, but fundamentally they’re going to have to deal with it, and we’re ready when they are.’

A good day’s work

Occupational medicine can bring huge benefits to individual patients and society, says Kathryn McKinnon, who first became involved while a GP in the military

Occupational medicine is a fascinating specialty, says Kathryn McKinnon, chair of the BMA occupational medicine committee, although she herself fell into it almost by accident.

‘I was originally a GP in the military, and a huge component of that was a small, niche part of occupational medicine, which is fitness for role, or fitness for task. So, I was very exposed to occupational medicine over the course of my military GP career and decided to make the change and move into higher specialty training.’

She worked as an occupational physician for the military for four years before re-entering civilian life and hasn’t looked back. ‘What I like about it is that it is hugely variable and broad-based and very much based around consultation with patients. I spend most of my clinical time talking to people, which is one of the reasons I wanted to be a doctor in the first place.

‘I also think as an occupational physician, you have the capacity to help not just the individual sitting in front of you – hopefully giving them advice on their medical circumstances and the effect of those on their work – but you also have the capacity to help whole cohorts or populations of individuals.’

There are essentially three parts to occupational medicine, she says: preventive; assessment; and treatment or therapeutic. ‘With the preventive side, if you can manage hazards, risks and hazard exposures you can reduce the risk of developing a work-related health issue for a whole cohort of workers – by, for example, reducing noise exposure, or chemical exposure, or exposure to respiratory hazards.

‘We can – along with our “hygiene” colleagues – quantify the risk and advise the employer on control measures.

It sounds quite boring and technical,’ she says. ‘But actually we stop people getting poorly in the first place.’

The other elements of the job support people who are unwell, either to stay in the workplace or to return to it. ‘That’s where the assessment and advisory role comes in, advising on fitness for role, whether it is pre-employment or whilst in employment, and on adjustments, support and/or rehabilitation, to try and keep people at work doing as much as they can, and trying where we can to give advice that helps them overcome any detriment they experience as a consequence of their health issues.’

Where occupational medicine differs from, say, general practice services, is that it is very much tailored to the consequences of an individual’s health issue, rather than focused on the diagnosis and treatment needs.

‘We make a holistic assessment of the individual,’ she says. ‘We will look at their function and the impact of any decline in function on their work activities and we will then try to give advice as to what medical or workplace interventions are going to be beneficial. In lots of cases, diagnosis doesn’t really matter.

‘If you’ve got a wobbly knee, for example, does it really matter if you’re an office-based worker who can work from home? Possibly not. But it would matter if you drive a bus, for example. So, in terms of whether an individual can do their job, the consequences [of the wobbly knee] may well be minimal or trivial.’

The ability to work is not regarded as a ‘health outcome’ in the NHS, she adds – meaning that conditions that stop people working aren’t necessarily given priority. ‘You can have a relatively low-level issue, which is a complete showstopper from a work perspective, but it doesn’t meet the threshold for urgent or even soonish treatment from the NHS, so people lose their jobs because they can’t get timely treatment. That’s not a criticism of the NHS – it’s just where we are.’

There are, she says, many, many people with physical or mental health difficulties who would love to be in the workforce but who are currently let down by a lack of access to occupational medicine services – which is devastating for individuals, but also terrible for the economy.

‘What we should be doing is giving people the support they need to do what work they are able to do, rather than penalising or criticising individuals for not being at work. The reasons why people aren’t at work are complicated. Generally speaking, work is good for you and it’s one of the greatest social determinants of health. Our role is to make sure that people can do what they can and can be supported to do as much as they can.’