Failed by the system?

Failed by the system?

Evie Wilson was a promising young artist. Her death at the age of 24 shows, in the words of her GP father, a lack of ‘shared understanding’ between the parts of the health service meant to serve vulnerable patients

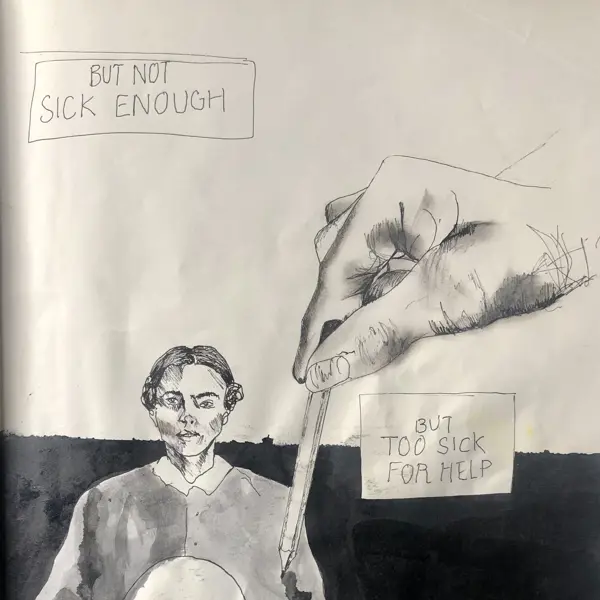

‘Not sick enough ... but too sick for help.’

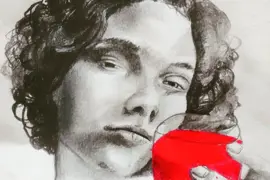

Evie Wilson describes her experiences of adult mental healthcare in one of her many powerful paintings. The talented young artist had been accepted on to a fine-art degree at Goldsmith’s months before she died in July 2022, aged 24.

Much of the ‘joyful’ and ‘mischievous’ young woman’s artwork, cherished by her grieving family, spoke to her six-year experience of NHS adult mental healthcare.

As a complex patient with multiple diagnoses, she was passed around services and, as her parents tell The Doctor, ‘never felt recognised’.

The coroner at Evie’s inquest concluded she died as a result of morphine toxicity, and her intent was unknown. Her parents say her death was ‘entirely avoidable’.

Evangeline May Wilson, known as Evie, had been diagnosed with bulimia, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and borderline personality disorder.

She had been passed around local adult mental health services by AWP (Avon and Wiltshire Partnership Foundation Trust) over six years and had a history of severe self-harm and suicide attempts.

Her GP had been aware of her eating disorder from her teenage years, after which her condition escalated following a traumatic event. She was admitted to hospital more than 50 times between 2016 and 2022, with some detentions under the Mental Health Act.

On 22 June 2022 she was admitted to Cassel Hospital, London, for what was intended to be a nine-month stay at the inpatient facility, which offers a ‘living and learning environment’ – where patients discuss their conditions and treatment plans with each other as well as clinicians in a ‘therapeutic community’.

Less than three weeks into her stay, Evie was placed on short leave after breaching Cassel’s no-alcohol rule, despite drinking being a relapse indicator in Evie’s AWP safety plan. She had told nurses she felt as though other patients ‘hated’ her and had had a seizure the previous weekend. On Friday 8 July she was released with a return train ticket to Bristol and her next therapeutic session planned for 12 July.

The leave was to give her extra time to ‘reflect’. But she never returned. Evie was found dead at her Bristol flat by police on 10 July 2022 with a toxicology report showing acute morphine toxicity. Evie’s parents say she was ‘naïve to opiates’.

Welfare calls

The inquest focused on the welfare calls which were supposed to have been made to Evie during her short leave – and whether she should have been allowed to return home to an empty flat at all.

It was agreed that, as her home trust, AWP was responsible for making welfare calls while Evie was on leave from Cassel. The inquest heard messages were sent by a doctor and nurse at Cassel to AWP’s consultant psychiatrist who had treated Evie previously.

On the Friday evening, he had forwarded a plan for her weekend’s care to AWP’s duty team – which consisted of two unregistered practitioners employed by a mental health charity commissioned by AWP. One responded to say making such calls was out of their scope and could ‘pit us against’ nurses.

The psychiatrist followed up to reiterate his plan should be followed, but those welfare calls were not made by the duty team, which at the time worked 9am to 5pm on weekends. The staff member who questioned the scope was off sick on the Saturday and the inquest heard the system relied on staff proactively checking emails to know about welfare call requests.

It was only on Sunday 10 July a call was made to Evie. This was made by the crisis team after a concerned call from Evie’s mother – not by the duty team which was supposed to call her. She was found dead by police that night.

During questioning of the systems in place at the time, and which have since been updated, coroner Peter Harrowing said: ‘Those calls were never going to be made.’

Dr Harrowing, however, found Evie’s short leave period was ‘appropriate’ given she was a voluntary, informal patient and safeguarding plans had been made. Although Evie’s family contended Evie faced a heightened risk at the time, he concluded the missed welfare calls were deemed ‘precautionary’ and therefore them not taking place was not ‘causative’ in her death.

AWP has since changed its welfare call practices following an internal investigation and Cassel Hospital has updated its assessment processes for new patients and when short leave is granted following a serious incident review. Both trusts offered their condolences. With the changes in mind, the coroner made no preventing future death statement.

In his summing up, Dr Harrowing said: ‘That a system can be improved does not in itself mean there has been a system failure.’

It was clear to us early on that the local mental health services were not meeting her needs

Evie's father, Dr Wilson

Evie’s father, GP Nick Wilson, told the inquest that her ‘complex difficulties’ got to a point where they were ‘out of our depth as parents’. Her mother, Sally Watson, has also worked in healthcare roles.

‘It was clear to us early on that the local mental health services were not meeting her needs,’ said Dr Wilson, who had asked for Evie to be referred to inpatient care locally – but the family’s funding request was declined in 2017. ‘There seemed to be an insurmountable hurdle for Evie to climb.’

Dr Wilson says his daughter’s mental health treatment at AWP involved ‘a lack of leadership’ and was ‘focused almost exclusively on medication’.

After deferring her degree for a year, Evie was finally referred to Cassel in September 2021. That was the last time her parents, who say it was ‘extremely difficult’ to work with AWP’s mental health team for six years, were directly involved in her care. They say there was ‘no contact whatsoever’ after that point despite several crises before her death.

While Evie had limited how much information could be shared with her parents, she had given consent for them to receive non-personal details.When in crisis, Evie would engage with mental health services but not her family. After Evie’s death, her parents found out that a psychiatrist had written, in capital letters on a review, that Evie did not have a personality disorder. A subsequent letter had supported this, yet Evie was still referred as an inpatient to Cassel, where having a personality disorder is a pre-requisite of being accepted.

When Evie was sent on short leave, her parents received ‘radio silence’ from Cassel Hospital. They only knew because her mum, Ms Watson, received a text from Evie saying ‘glad to be home’.

‘She was very vulnerable,’ Dr Wilson, who was on a camping trip in Cumbria with Evie’s two brothers when he received news of her death, recalled at the inquest. ‘Had we known she was home, and at high risk, we would have made ourselves available.’

Evie’s parents’ concerns about her care speak to some of the issues raised in a recent BMA report into the failures of the ‘broken’ and ‘dysfunctional’ mental healthcare system in England, published the week of the inquest.

The report found growing levels of complexity among mental health patients and limited opportunities for psychological therapies in stretched services. As a result, patients are increasingly ‘falling through the gaps’, ‘leaving a significant group of patients with nowhere to turn’. Patients with suicidal ideation find it particularly difficult to access talking therapies, the report found. One psychiatrist said when a patient becomes suicidal, it ‘becomes like an exclusion’ from treatment such as CBT through NHS England’s flagship Talking Therapies programme.

Sense of isolation

Speaking to The Doctor, Evie’s parents say her level of complexity was ‘absolutely central’ to the substandard care they say she received; being considered too complex for treatment in primary care, self-harming behaviour preventing eating disorder treatment, question marks over her personality disorder diagnosis being ignored, and ‘light-touch’ involvement from consultant psychiatrists.

‘They didn’t know what to do with her,’ says Evie’s mother, Ms Watson. ‘They kept saying you can’t run more than one therapy at a time.’

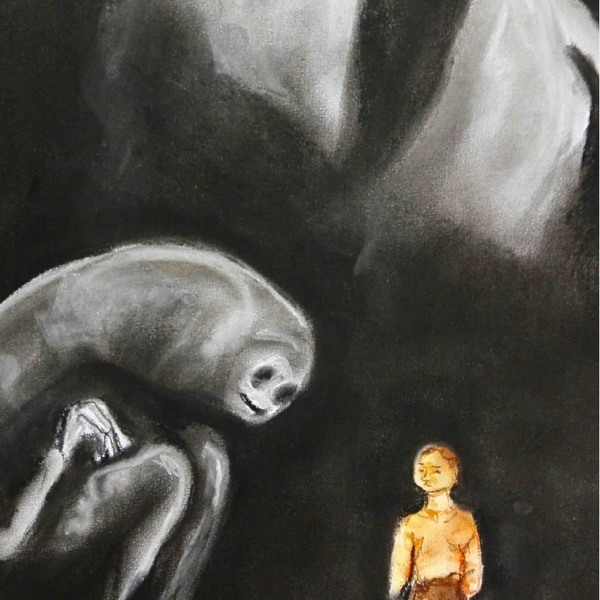

The frustration was evident in Evie’s artwork. She expressed feelings of isolation, of a beastly, intimidating system towering over her. ‘Why can’t you see me?’, she asked in one piece.

Her parents say her death was 'entirely avoidable'

Evie had multiple care coordinators during her care: her family estimates about 10. They have no complaint with the individuals but say the system – and high staff turnover – affected Evie’s care, losing vital continuity.

As her father puts it: ‘There wasn’t ever a shared understanding between her and the people looking after her. She died thinking that no one really got her.’

The BMA report recommends that NHS England expands opportunities for talking therapy to address the gap in provision. It also calls for more dedicated care coordinators and says different parts of the health and care system often find it difficult to work together. This, it says, is often ‘impossible’ because of the ‘extreme pressure’ those working in the system are under, but also because of ‘siloed services’ and ‘tension between different parts of the system’.

Doctors told the BMA this could be frustration from GPs at refused referrals, or pressures on secondary care teams to ‘bounce back’ patients because they don’t have the resources to meet demand.

Evie’s parents say her hospital admissions were treated as isolated incidents with notes ‘just filed’ with ‘no follow-up’, primary care ‘assuming the mental health team are on it’ and mental health teams saying she was not suitable for their services.

‘Someone needs to stand back and take a holistic view,’ says Dr Wilson, who believes mental health teams should ‘empower’ patients’ families and friends, ‘especially if the service is over-stretched’.

She knew she was falling between two stools, constantly waiting for someone to wake up and smell the coffee. It was exhausting

Ms Watson

Long waiting lists, and higher thresholds for receiving care, are also issues identified in the BMA report which align with Evie’s experiences.

‘It was a bit Alice in Wonderland,’ says Dr Wilson, explaining how Evie was expected to attend a tier 3 service before being admitted to tier 4 – when no tier 3 service existed locally.

‘It was Cassel or nothing,’ he says of the centrally-funded tier 4 service that obviated the need for local funding.

‘She was told she was too ill for the eating disorder service, but not ill enough for an inpatient setting,’ recalls Ms Watson. ‘Her maladaptive coping strategies became more entrenched. She became unrecognisable.

‘She knew she was falling between two stools, constantly waiting for someone to wake up and smell the coffee. It was exhausting.’

Disjointed system

Frustration at this led to pursuing the out-of-area specialist admission at Cassel Hospital, which her parents now describe as a ‘fatal’ decision. While the inquest heard of multiple assessments Evie undertook before admission to Cassel, and that the hospital deemed her ‘suitable’, her parents say acute admissions in the months before her referral should have raised alarm bells.

The BMA report says the issues it has identified, including those experienced by Evie, have been exacerbated by the lack of sufficient funding or staffing for mental healthcare.

The Government has pledged to increase mental health funding by £2.3bn a year in real terms by 2023/24 compared with 2018/19, but the BMA recommends restoration of the public health grant to 2015/16 levels, which would mean an additional £1bn a year. Mental ill health has been estimated to cost the UK economy £118bn annually.

Without adequate funding, the report says, ‘the NHS will continue to haemorrhage staff, patients will receive worse care, and we will be a poorer society for it’.

Targets, it adds, are often ‘unambitious’, and – coupled with a lack of consistent data to show the prevalence of mental illness – it is difficult to know how much funding and staff is needed.

It is a sentiment Evie’s parents agree with. And while the coroner concluded that no systemic failures caused their daughter’s death, they say the disjointed mental healthcare system manifests itself as ‘complacency’ and a ‘lack of professional curiosity’.

In a statement released after the inquest’s conclusion, they said: ‘Our faith in a professional, caring and effective healthcare system has been shattered.’

There wasn’t ever a shared understanding between her and the people looking after her. She died thinking that no one really got her

Evie's father, Dr Wilson

Evie’s parents keep her artwork displayed on their walls. For Dr Wilson, a collage she made as a 10-year-old hangs in his consulting room; a reminder of her ‘lovely, naïve’ childhood – before her mental health challenges set in.

‘Life is a paler colour without her,’ says Ms Watson as she describes her daughter as ‘bright, vivacious, interesting, sharply funny with a wicked sense of humour’.

Those characteristics are so vividly and poignantly present in Evie’s artwork – artwork that tells the first-hand story of a complex mental health patient who felt ignored in a broken system.