Emergency measures: doctors' struggle against climate change

Emergency measures: doctors' struggle against climate change

Global warming is considered a threat to health by many doctors, some of whom are prepared to take direct action to make their voices heard

19 July 2022 was the hottest day ever recorded in the UK, reaching 40.3°C in Coningsby, Lincolnshire.

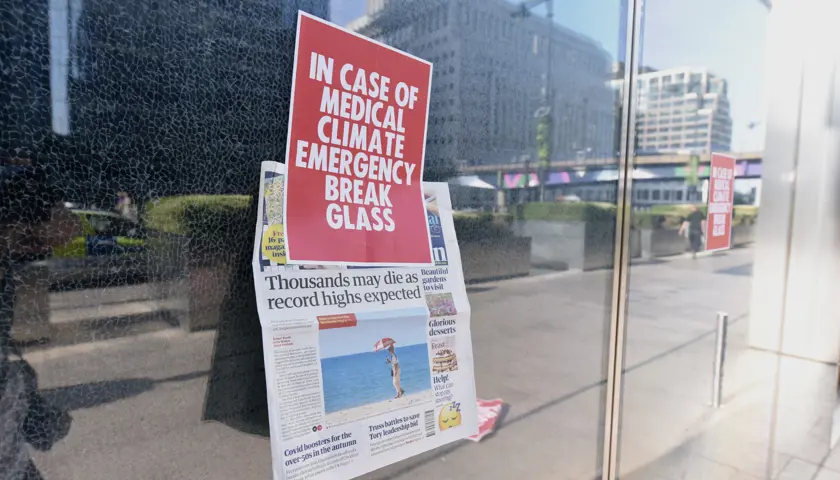

Two days earlier, six medical professionals – including four doctors – broke glass windows at the Canary Wharf offices of banking giant and major fossil-fuel financier JP Morgan as they saw forecasts of a record heatwave.

After they ‘carefully cracked’ the windows, they put up posters saying, ‘IN CASE OF MEDICAL EMERGENCY BREAK GLASS’.

They say the climate emergency is also a health emergency and point to evidence-based studies, which show direct action is the most effective way to affect change – in this case ending the burning of fossil fuels.

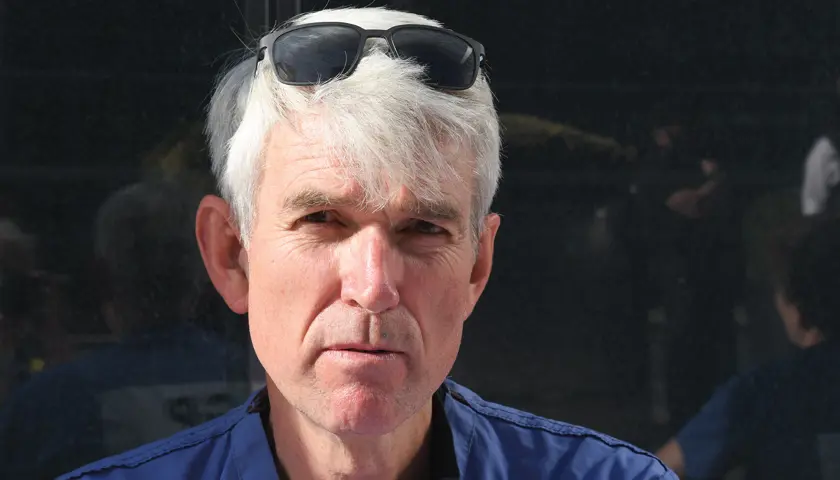

Two years on from breaking the glass, which JP Morgan says cost nearly £200,000 to replace, the six – consultant psychiatrist Juliette Brown, GPs David McKelvey and Patrick Hart, consultant in obstetrics and gynaecology Alice Clack, dementia specialist nurse Maggie Fay and child and adolescent mental health specialist Ali Rowe – went on trial accused of criminal damage. They pleaded not guilty at Snaresbrook Crown Court, London, in June.

Climate change is making us sick, and urgent action is a matter of life and death

World Health Organization

Shortly before the trial began, the judge ruled that the defences the defendants had planned to use were not available to them. These defences included that of belief in consent, which is where those alleged to have committed the offence believe the persons they understand to be entitled to consent to the destruction or damage of the property had so consented, or would have consented, if they had known of the damage and its circumstances.

The judge said the defence was not available as the factors upon which it was based ‘do not include the political or philosophical beliefs of the person causing the damage’ and consent ‘was not intended to afford a defence to protesters based on the merits, urgency or importance of their cause’.

But he did allow them to speak on their motivations for taking action; namely that they believed it was their obligation as health professionals to do what they could to prevent the damage to people’s health they said would be caused by the continued burning of fossil fuels that JP Morgan helps facilitate – the bank has financed US$432bn (£341bn) of fossil fuel deals since the UN’s 2016 Paris Agreement, a treaty aimed at limiting the global average temperature rise to 1.5°C.

No regrets

At the end of the trial, the jury did not reach a verdict. A retrial is slated for 2026.

The impasse has left the four doctors in limbo, their careers potentially in jeopardy if a retrial finds them guilty of criminal damage.

Their case follows that of GP Sarah Benn, who received a five-month suspension from a MPTS (Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service) hearing, which found that her environmental activism and resulting convictions amounted to misconduct. The BMA is supporting Dr Benn, who retired from clinical practice in 2022, with an appeal.

Still working, and with legal bills to pay, the effect on the JP Morgan doctors’ lives could be momentous. Speaking to The Doctor, Drs Clack, Brown and McKelvey say they have no regrets.

As medical professionals, they are keen to point out that their reasons for taking non-violent direct action over the climate emergency are evidence-based.

The term ‘climate emergency’ is recognised by the UN and many leading global organisations agree it is a health emergency, too.

The Lancet, in 2021, said: ‘Health is already being harmed by global temperature increases and the destruction of the natural world,’ noting: ‘The science is unequivocal.’

This year’s Lancet Countdown urged a divestment from fossil fuels on health grounds, saying: ‘Climate change is the greatest health threat facing the world in the 21st century.’

A World Health Organization special report for this year’s COP29 declared: ‘Health is the argument for climate action,’ noting: ‘Climate change is making us sick, and urgent action is a matter of life and death.’

Director general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in the foreword: ‘The climate crisis is a health crisis.’

In the month the four doctors were involved in the action at JP Morgan there were 3,898 excess deaths in the UK.

The Office for National Statistics said some were associated with the ‘exceptionally hot weather’.

This August, a study published in Nature Medicine showed that heat ‘fuelled by heat-trapping greenhouse gases’ killed nearly 50,000 people in Europe in 2023.

It’s been a journey about health justice and how we frame health in general as a profession

Dr Brown

‘We have an existential crisis unravelling and we’re not doing anywhere near enough to stop it,’ Dr Clack tells The Doctor. ‘It’s a massive health issue. And the response is completely inadequate.

‘As health workers, we have a responsibility to stand up, make clear what’s happening and draw the public’s attention to the fact that this is a huge public health catastrophe, that the establishment is not protecting health and something radical needs to change.

‘As health workers we have even more responsibility, not just because we have a code of conduct to protect public health but because we have a trusted voice within society.’

The doctors point to studies which prove how direct-action campaigners throughout history have effectively driven change, such as Australian doctor Arthur Chesterfield-Evans, who was convicted of ‘wilfully marking premises with paint’ when taking on big tobacco advertising by ‘re-facing’ billboards in the 1980s (his sentence was remitted on appeal).

Health and care professionals should recognise the climate crisis as a health crisis

Government guidance

‘Somebody has to take responsibility,’ says Dr Clack. ‘And it’s potentially very powerful to have people with trusted voices doing that. We have a professional responsibility to follow the evidence and we’re well-placed to do that because we’re trained scientifically – and are communicators.’

The Government’s own guidance can be interpreted to support the argument, too. Its document on climate and health says: ‘Health and care professionals should recognise the climate crisis as a health crisis, and therefore climate action as a core part of their professional responsibilities.’

For change to happen, Dr Clack believes ‘it needs people who are in a position to actually change things to recognise what’s going on and risk what they’ve invested in – which is a system that is going to destroy us.’

Dr Brown adds: ‘We still see lots of climate health leaders who think if we keep telling people how bad this is and keep quoting the numbers of how many people are dying because of air pollution or environmental damage worldwide that’s going to change things.

‘For me it’s been a journey about health justice and how we frame health in general as a profession. We put this responsibility on people for their individual health and we don’t look at it in the context of social and political decisions that are being made constantly which undermine people’s health and limit their access to health justice.’

Asked how she felt sitting in a courtroom for, in her view, doing her duty as a doctor, Dr Brown says: ‘If anything I was feeling more certain we did the right thing.

‘There are hundreds of thousands of people worldwide who want change to happen quickly and it feels like, as medics, we need to stand alongside those people who are taking enormous risks, here and overseas. We have the credibility, the reputation and we have a lot of security where we are, not just in the UK but as [medical] professionals.’

Dr Clack also felt ‘very certain’ the doctors had done the right thing.

‘It’s been a rollercoaster,’ she says. ‘Working in a very conventional profession, you’re often trying to explain why you did something like break a bank’s window to people who are fully embedded in this system where everyone is acting like it’s fine and there have been periods where it felt bizarre.

‘You have to keep reminding yourself of the facts of the situation, what the science says and that this sort of action is necessary.’

Greater purpose

Dr McKelvey says: ‘It was the right thing, but at the time you go in there and you’re stepping up to the threshold from being a “good citizen”, stepping up to a boundary where you are potentially going to be found guilty of causing criminal damage.

‘That was a moment of feeling very nervous and unsettled. But while you’re going into a place of potential personal difficulty, you’re doing it for the motivation of something bigger than yourself. That’s why we could go into the courtroom and stand tall.’

With the retrial listed for 2026, the doctors face a long wait for a decision and feel a continued sense of not knowing what lies ahead.

This year, some climate activists were jailed for record terms of four and five years for non-violent direct action, being found guilty of conspiracy to cause a public nuisance for their roles in planning to block traffic on the M25 motorway. The sentences were longer than many handed to people found guilty of violent disorder in recent far-right riots.

The UN’s special rapporteur on environmental defenders, Michel Forst, said the climate activists’ sentences represented ‘a dark day for peaceful environmental protest’ in the UK and ‘set a very dangerous precedent’.

In that case, defendants including Just Stop Oil co-founder Roger Hallam had their evidence discontinued when defying the judge’s ruling not to discuss their motivations on the basis they did not amount to a defence, but rather a ‘political or philosophical belief’ – as upheld by the Court of Appeal.

In the JP Morgan case, the judge told the defendants, and the jury, that concerns about the climate emergency were not a defence for criminal damage, but he did allow the doctors to speak about their motivations in court.

‘That he let us speak meant all the information was there [for the jury],’ says Dr Clack. ‘Some of them felt that we had a valid reason for doing what we did, regardless of the written law.’

She adds: ‘The law changes all the time. Two years ago, we would have had a number of legal defences. That was all withdrawn, so we had to defend ourselves outside of the written law.’

Dr Brown says: ‘We made the moral case, and the jury clearly had a lot to think about around the question of intent.’

Dr McKelvey said the financial cost was his biggest concern, with the group having already racked up legal bills in excess of £80,000. ‘If we go to a retrial we would have another tranche of costs,’ he explains. ‘And if we’re found guilty then of course we’ve got more problems.’

The group has launched a fundraising page, which has so far raised more than £50,000 towards the £85,000 target.

Career in jeopardy

For Dr Clack, the main concern is being referred to the GMC.

All criminal convictions, whether they result in immediate imprisonment or not, are automatically referred to the regulator, as was the case for Dr Benn who earlier this year had her licence to practise suspended for five months after being found in contempt of court for breaching an injunction by ‘spreading out and sitting down across the road’ at Kingsbury Oil Terminal holding a placard saying ‘stop new oil’.

The BMA is supporting Dr Benn with her appeal against the MPTS finding that her actions amounted to misconduct despite ‘no clinical concerns’.

Another retired GP, Diana Warner, had her licence suspended for three months following an MPTS hearing in August. She was found in contempt of court for breaching an injunction by protesting on the M25 motorway in October 2021.

‘Given the fitness-to-practise tribunal appears to have been a tick-box exercise, [conviction] would probably mean we would lose our jobs,’ says Dr Clack. ‘I would be scared to go to prison, but I would be more worried about my potential to work and my livelihood.’

A motion passed at this year’s BMA annual representative meeting urging the association to lobby to safeguard the rights of healthcare workers and medical students engaged in activism.

The motion calls for the BMA to work with the GMC to develop guidelines that protect doctors’ rights to protest and express themselves lawfully, ‘especially in relevant contexts such as climate change’.

For the doctors facing a retrial, the word ‘lawfully’ potentially confuses the level of support, and they believe the motion should have gone further.

Dr Clack says it is ‘reassuring’ that the BMA has offered its support to Dr Benn and says direct action is ‘only possible because of the support of other people’.

Dr McKelvey adds that the ‘binary’ point about whether action is within the law or not, ‘doesn’t allow for the nuance of the motivation and the way [action] is carried out’.

He says: ‘We carried action out early on a Sunday morning, had done a risk assessment and made it as safe as possible. You don’t want carte blanche saying any unlawfulness is OK [which suggests] you can drive a JCB into JP Morgan at any time of day. That would clearly be nonsense.

‘What we would want is an acceptance that non-violent direct action is an evidence-based social change theory.’

You’re doing it for the motivation of something bigger than yourself

Dr McKelvey

There are about 500 people on the Health for XR mailing list, with approximately half of them doctors. Around 150 ‘regularly support protests’, the doctors say, noting that there is crossover with other environmental groups of health professionals such as MedAct and Health Declares which focus their efforts on areas such as health inequalities and divestment from fossil fuels in non-direct action.

Dr Brown says: ‘What we did takes a huge amount of support’, be it financial, emotional or logistical.

She adds: ‘We would never judge people for not taking part. It’s really difficult to take these kinds of actions. But there are lots of other opportunities to be supportive.’

Dr Clack notes: ‘Most of the action we take doesn’t get people arrested. That whole range is necessary. We have to do what is effective and has the evidence base.’

Dr McKelvey adds: ‘We’re always looking for something that’s appropriate and is going to shift the dial. The climate crisis is escalating and our health service is under threat.

‘As activists, we’re really trying to grapple with this. We are struggling to see how we, as humans, and particularly as healthcare workers, can be the best people we can possibly be when faced with this massive issue.

‘We’re heading for catastrophe. How do we break the business-as-usual cycle?’

Dr Brown says: ‘Every individual should take whatever decision is right for them.

‘We are fully aware that there are lots of people for whom this kind of action is more complicated and risky – people who are not treated as well by society as we are as white middle class doctors.

‘But there are thousands of people taking these kinds of actions because they recognise what’s at stake. Once you grasp what’s at stake, it’s difficult to sit back and do nothing.’

(Photo credit: Gareth Morris)

Lead image (left to right): Maggie Fay, Alice Clack, Patrick Hart, Ali Rowe, David McKelvey and Juliette Brown