Children under pressure

Children under pressure

BMA research shows the mental health of children and young people in England is worsening. Support services in the NHS and schools are not sufficiently resourced to meet the growing demand. Patients struggle to find the help they need, which harms them, their families and staff working in areas under extreme pressure. Peter Blackburn reports

Danny* was 16 when things spiralled to the point where family and sixth-form teachers urged him to go to see a therapist. He was struggling with anxiety and low moods – and those struggles had become all encompassing, affecting education, sleep and all parts of life.

His therapist eventually directed him to NHS CAMHS (child and adolescent mental health services). Danny had no idea what to expect – he knew only that those around him hoped this would be the help he needed.

Help ended up being a long way away, however. It took nearly a year for him to be assessed for the first time. ‘For most of that time I thought I had been forgotten about. The waiting time was ridiculous,’ the now 20-year-old from the south-west says.

Upon eventual assessment, Danny was immediately referred to the crisis team – a decision reflecting the seriousness of his struggles and one which puts the long wait without care and support into even starker context.

‘Even then, there were still months between updates and different people and teams would contact me. The system felt confusing as I wasn’t communicated with about what I was waiting for or how we would find solutions to my problems. It just adds stress to what someone may already be feeling.’

Fragmented system

Danny had mixed experiences of a fragmented system. Some staff showed real care, but sessions were ‘always rushed and short’ and lots of different staff members meant mixed messages and, ultimately, feeling like there was ‘no clear plan or constant support’ particularly if struggles became ‘urgent’.

For Danny and his family, it felt that there was little choice but to find a doctor and therapist outside NHS CAMHS services. These staff, Danny says, ‘actually have the time and structure to properly help’.

Danny’s story is far from unusual.

The Doctor can reveal that an in-depth analysis of NHS data and interviews with doctors, other health professionals, local education senior leaders and patients, and families paints a stark picture of increasing need unmatched by resource and a rapidly spiralling complexity in conditions young people are presenting with.

The mental health of children and young people in England is worsening, and record numbers of children presenting with mental health difficulties are placing increasing demand on mental health support both in the NHS and in schools.

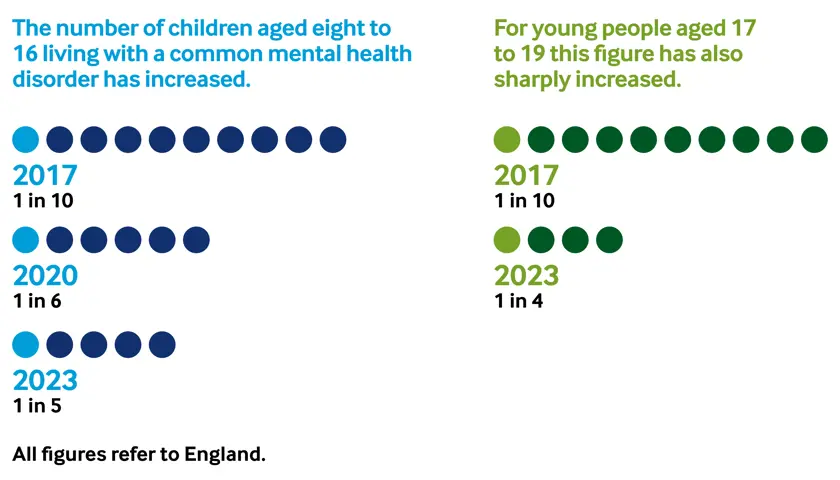

In 2017, one in ten children aged eight to 16 were living with a common mental health disorder. By the onset of the pandemic in 2020, that figure had risen to one in six, and by 2023 it was one in five. For young people aged 17 to 19, rates increased from 1 in 10 in 2017 to 1 in 4 in 2023. This sharp rise in need has not been matched by investment or capacity in mental health services. It is an equation which leaves too many children falling through the gaps in an overstretched system.

A Yorkshire GP gives one example of that scenario playing out. She explains a recent case where a parent was asking for help. Their child had a learning disability, was on the autistic spectrum and had poor mental health – some of which resulted in criminal offences. There were no avenues of support willing to help, including charities, because the young person was deemed a threat and the family received no support to help effect their behaviour change.

Between January 2020 and October 2025, the number of children and young people in contact with NHS mental health services monthly has more than doubled.

‘The statistics echo the experiences of my colleagues,’ consultant forensic psychiatrist John James Alexander Moore says.

‘I’m a relatively new consultant, just a couple of years in, and there’s a cohort of us who are newly taking these levels of responsibility. Case load numbers are particularly unsustainable in CAMHS. I frequently hear of friends expected to cover for absent colleagues. Children and young people are having to reach an absolute crisis to meet thresholds for services because waiting lists are so long and some waiting lists are measured in years rather than weeks or months.

‘Too often there’s a sense that children need to be actively trying to end their life in order to be properly supported by services. Purely having an obvious mental health illness or self-harming is sometimes not enough – that gives you a sense of how strained services are.’

Children and young people are having to reach an absolute crisis to meet thresholds for services

John James Alexander Moore

The statistics are heartbreaking. Anxiety was the most common reason for referral to mental health treatment according to the latest data from 2023/24, with 16 per cent of young people struggling with that diagnosis. According to the same data around 8 per cent of the 12 million children in England were referred to CAMHS services and monthly referrals have surged year on year.

In 2016 that figure was 40,000 but latest figures put it at around 120,000. Perhaps even more worryingly, of those referred only 36 per cent received support, 33 per cent were waiting for support and 31 per cent had their referrals closed before assessment. Professionals fear what difficulties might be out there – ignored or avoided.

It is hard to brand rocketing waiting times – in the face of so much need – as anything other than a scandal. In 2023-24, 18,500 children waited between one and two years to enter treatment and 8,300 waited for more than two years. Of these children the mean waiting time was three years and five months.

For many these waiting times exacerbate existing difficulties, families are left dealing with struggles as to which they have no expertise and treatments that could have enormous positive effects are being missed out on.

One consultant psychiatrist says many patients waiting for assessment for something like ADHD are missing out on medicines which could change their relationship with education and the stress of their personal lives.

It is not just the amount of young people and families needing support which is spiralling, but also the complexity of that need. Waiting lists are stubbornly high, especially for those with additional learning needs or neurodevelopmental disorders. Anxiety and eating disorders are on the rise, as are physical symptoms which often mask underlying psychosocial stress.

Social media

One consultant CAMHS psychiatrist from the north-west says there has been a significant deterioration in young people’s mental health since COVID – but particularly among young women with eating disorders and with people whose conditions had underlying social causes.

A Yorkshire consultant psychiatrist describes demand as having ‘skyrocketed’ and particularly highlights increasing numbers of referrals from a neurodevelopmental perspective.

A GP working in the West Midlands raises concerns for the future, too, saying poor mental health in children is at an all-time high with the younger generation facing many new issues including social media, tech, and a lack of awareness about the potential impact of these things. She says parents haven’t navigated this sort of complexity before. The GP, who is particularly seeing children with depression, who are self-harming and who are suicidal, says: ‘I’m not sure the health service is ready for what is to come.’

And a paediatric specialty doctor in psychiatry, based in Yorkshire, warns that the kind of children who are being admitted to inpatient units now have real complexity or difficulties in that there aren’t one or two problems but three to five diagnoses.

He says young people’s intensive care units will often have patients with a combination of diagnoses like psychosis, neurodiversity, substance misuse problems and learning difficulties. This sort of complexity, he says, means inpatient stays are increased significantly and patients spending a long time in hospitals don’t necessarily just get better – sometimes they acquire more detrimental, negative, or dysfunctional coping styles particularly from copycat behaviour.

Speaking to The Doctor, the head teacher of a hospital school in the north of England, said his organisation was seeing a massive rise in need for mental health services, but also the exponential growth of children presenting with multiple issues – including many experiencing trauma-related conditions.

‘We are seeing a real significant cohort of vulnerable young people requiring a very bespoke and holistic package of support. These mental health issues impact every aspect of the child’s life – it’s not just education but it’s social relationships, family dynamics, their overall wellbeing.’

The head teacher recalls one recent pupil. ‘She was an extremely academically able young person… she was significantly struggling with generalised anxiety… she had missed so much education from a mainstream setting. She was almost punishing herself through self-harm because she felt she was letting herself, her peers, her family and her school down. She was so distressed at the fact she couldn’t access the curriculum available in a mainstream setting.’

The results of demand exceeding capacity are brutal: higher thresholds for support are crystallised, children are turned away from services and people even begin to avoid making referrals due to extreme delays. Nowhere is this more stark than in neurodevelopmental services assessments may take 10 months before a 2.5-year wait for services and in paediatric teams which have waits of up to eight years for autism or ADHD assessments.

Another result of extreme demand and high thresholds is that there can often be a lack of clarity about service availability and criteria, and frequent changes can make navigation difficult. This is compounded in a fragmented system in which GPs try to bridge gaps between services run by different teams and providers and children are sometimes discharged immediately just for missing an appointment or failing to respond to a letter.

Impact on families

These are all issues which affect the wellbeing of young people and their families. Policy documents and think-tank reports will use words such as fragmentation to describe the state of the system but rarely is it captured what these abstract-feeling concepts actually mean for people.

Michael Hibbert is a father-of-two from Sherwood in Nottingham. Mr Hibbert’s daughter was diagnosed with an eating disorder at just 13-years-old and was referred to CAMHS for support around 18 months ago. What the family found was a system in which staff left so regularly – with enormous pressures, often poor conditions, and massive vacancy lists prevalent – that four different workers were assigned to her care within the first six months alone.

‘This for a teenager who was going through things growing up and all the other things teenagers have to go through meant she had no faith in the system,’ Mr Hibbert says.

‘She basically had no confidence in talking to them – they are just doing their job and do not see her as a person, just someone they’ve been given.’

Mr Hibbert adds: ‘It really took its toll on my daughter, my wife, and myself. We really felt like we were just a number at every meeting. Without confidence from kids who go there and without them feeling that CAMHS genuinely care about them, kids will not feel confident to open up. The only way that’ll happen is for both keeping staff and also making kids feel like they are there for them and not just next on the list.’

Mr Hibbert wants to see a system which recruits and retains its people better, with people with lived experience welcomed and involved. As a result, he hopes young people would feel cared for rather than just being a name on a list.

He says: ‘It has been an awful experience as parents. Being told your daughter is going through what she is, knowing it’s happening at home whilst you are in the house and not knowing what to do to help. I honestly cannot put into words how useless you feel or how much you doubt yourself as a parent.’

Maybe half of my new consultant colleagues have already been off work with burnout and stress

John James Alexander Moore

The hospital school head teacher has seen these nightmares play out many times after more than a decade leading his organisation. ‘Families feel completely abandoned,’ he says.

‘They feel completely unsupported during the most critical period of their child’s life. It impacts their own wellbeing as well as that of their child.’

He adds: ‘The results are increased feelings of isolation, a real emotional toll, difficulties in maintaining friendships and being engaged in community activities. Those service gaps mean interruptions in their learning journeys, missed qualifications and, ultimately, their life chances being reduced.’

Of course, the impacts are not limited to patients and families. The intolerable nature of working in stretched services and being unable to provide the care you want to can be brutal for staff too.

Newcastle-based Dr Moore, who is the BMA mental health lead, says: ‘It can just be exhausting knowing that you’re not able to deliver what you would want to. There are times when I know that family and friends haven’t received good enough care. We have a problem of a revolving door of patients who are far too ill by the time they come in and are also perhaps discharged before they are ready to be out.

‘It is taxing for staff. Maybe half of my new consultant colleagues have already been off work with burnout and stress.’

The BMA has produced a set of recommendations in the light of this investigation. It suggests that early interventions in mental health services to prevent children and young people reaching crisis point are of paramount importance.

These sorts of changes could include mental health support teams in schools and Young Futures hubs – a recent government initiative which aims to bring services together in one place to help teenagers at risk of gang violence or mental health struggles.

Making a difference quickly is key, the hospital school head teacher says: ‘The lack of intervention has a snowball effect. It worsens the condition and then increases the pressure on all of the services around them’.

The association is also calling for stronger collaboration and communication between different services to close gaps in care and avoid young people falling through the cracks. This would mean more integrated working, clearer referral pathways between services and improved signposting and information sharing systems.

Doctors leaders are also urging the Government and Department of Health to commit to a full assessment of unmet need in order to determine the level of funding required.

There can hardly be any overstating how important it is that these issues are tackled – and tackled with haste. So many patients like Danny feel ‘forgotten about’, so many parents like Mr Hibbert struggle to sleep at night wondering what they can do, and so many staff like Dr Moore’s colleagues are being harmed by the working environment they are trying to provide care and compassion in.

The consequences are already dire – children’s mental health is spiralling, their life chances are being reduced and the system is left trying to help when it may already be too late to have a proper impact. The arguments for action are inescapable. The results of inaction potentially catastrophic.

All professionals aside from Dr Moore have been anonymised as per the conditions of the study and patients and families have had their names changed in order to provide them freedom to speak out about their experiences while still using services

Additional work by Isabella Kerr