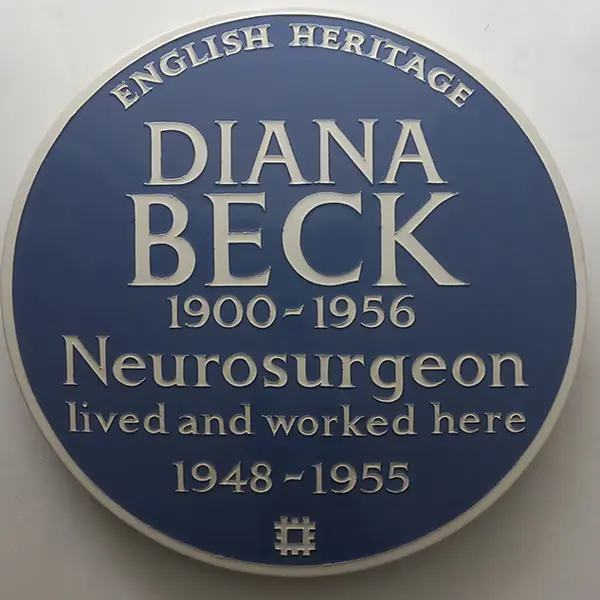

Blue plaque for pioneering doctor

One of a few select women to be commemorated under the scheme, Diana Beck was the UK’s first female neurosurgeon

When Diana Beck was elected consultant neurosurgeon at the Middlesex Hospital in 1947, she was the first woman to have been appointed as such in one of the great London teaching hospitals. Ironically, the hospital did not at the time admit female medical students.

She herself had graduated in 1925 from the London (Royal Free Hospital) School of Medicine for Women and specialised in neurosurgery, training under the great neurosurgeon Professor Hugh Cairns in Oxford. At the time, it was a relatively new and exciting specialty, and Diana Beck helped put it on the map.

Among other claims to fame, she operated on Winnie-the-Pooh author AA Milne after he had a stroke in 1952 – The Times newspaper described it as ‘a remarkable piece of surgery’.

She is known for jumping on a plane to Nigeria with just a few hours’ notice when she heard about someone who had a depressed cranial fracture – because she knew she could help. She also made an important contribution to neurosurgical treatment of intracranial haemorrhage.

Now, 99 years after she first qualified in medicine, she is being honoured with an English Heritage blue plaque. Unveiled on 5 September, the plaque has been installed at her former home and consulting rooms at 53 Wimpole Street, in London’s Marylebone.

She becomes one of a select few women doctors to be commemorated under the London-wide blue plaque scheme.

‘The standout achievement is that she was the first British woman neurosurgeon,’ says Howard Spencer, senior blue plaque historian with English Heritage.

‘She’s a glass ceiling breaker, there’s no doubt about it. It’s sad that she died at the age of 55, because she would have gone on to achieve a lot more.’

Katie Gilkes attended the unveiling. Currently a consultant neurosurgeon at the Walton Centre in Liverpool, she first became aware of Diana Beck while training at Bristol’s Frenchay Hospital. ‘One of the consultants mentioned to me that a woman had founded the unit. I was surprised about that because I’d no idea that was the case, but I had her name an did a bit of digging.’

As part of her research, Miss Gilkes uncovered Diana Beck’s obituaries from The Times and the BMJ and also found copies of papers she’d written – and then she wrote her own paper in an attempt to recognise her achievements. ‘I collated this information and found out she was pretty remarkable. She’d set up the neurosurgical unit at the Frenchay and at the Middlesex and she was the first female to be appointed to the staff. At the time it was a completely male consultant body, so she was probably the only female doctor in the establishment.’

When Miss Gilkes entered neurosurgical training two decades ago, it was still relatively rare for women to progress in the specialty. ‘It obviously wasn’t as unusual as it was in Diana Beck’s day, but it was still unusual,’ she says. ‘I would say that some of the challenges I’ve found in my career have possibly been similar to hers, but not on the scale she would have experienced.’

Fitting in

Diana Beck was ‘up against it’ in many ways, she adds. She had myasthenia gravis – which was at first dismissed as ‘hysteria’. (She died, aged 55, after surgery.)

‘I would say it’s still the case that if you don’t necessarily fit in with the crowd that’s already there, then professional life can be more challenging,’ says Miss Gilkes. ‘And she had it in spades – I don’t even know where she would have got changed [before performing surgery] and I’m sure a lot of the discussion would have been in the male changing room.’

Although more women are going into neurosurgical training today, they still make up a small proportion of consultants, she adds, probably around 10%. She credits a mentor of hers, Mick Powell, for persuading English Heritage to honour Diana Beck with a blue plaque.

‘He was quite taken aback that he hadn’t heard of her and described how in Bristol, there were pictures of all the founders of the unit and she didn’t really feature. Likewise at the Middlesex, he was using her office and had no idea that she’d been there. He made the nomination.’

To an extent, he was pushing at the open door. English Heritage is trying hard to increase the number of women honoured by the blue plaque scheme, which has been running for more than 150 years. The first plaque (to the poet Lord Byron) was erected in 1867 by the (now Royal) Society of Arts. The scheme was administered by the London County Council from 1901, then the Greater London Council from 1965, before being taken over by English Heritage in 1986.

Members of the public can nominate recipients of blue plaques, who must have been dead for at least 20 years, and must have a link to an existing London building where they lived and/or worked.

A panel considers all nominations according to set criteria, which includes that they ‘should be of significant standing in a London-wide, national or international context’, and that they ‘should have made some important positive contribution to human welfare or happiness’.

‘We’ve been trying to increase the number of plaques to individual women in a concerted way since 2016,’ explains Mr Spencer. ‘At that point, I think the number of plaques to women was running at about 13 to 14%, so pretty low – although in comparison, I think the Dictionary of National Biography was running at around 10 per cent.

‘It is a problem, and so there was a concerted effort to encourage more nominations from the public for women, and it has worked – this year we’re putting up more plaques to individual women than we’ve ever done before in a single year (10, compared to four to men).’

It’s slow work to ‘shift the dial’ because history has tended to erase the contribution of women, says Mr Spencer. This can lead to other complications too – although English Heritage is pretty confident that Diana Beck was the first female consultant neurosurgeon, they were wary of stating that on the plaque, and not only because of considerations of space.

‘The danger is that once you’ve committed it to a building – and they’re not easy to get out again, once they’re in – that somebody is going to pop up and say “well actually, have you considered X”,’ he says ruefully. ‘Because of women’s history often being buried to an extent, this kind of thing does happen from time to time. But we’re pretty confident that she was the first to be working in this country and very early on a global scale.’

- For more information on the London-wide blue plaque scheme, including how to nominate someone (who has to have been dead for at least 20 years) see the English Heritage website: https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/

Medical women with a blue plaque under the London-wide scheme are:

- Elizabeth Garrett Anderson – the first woman to qualify as a doctor in Britain. Plaque is at 20 Upper Berkeley Street, Marylebone, where she practised from 1865 to 1874

- Diana Beck – neurosurgeon, 53 Wimpole Street, where she lived and worked from 1948 to 1954

- Margery Blackie – doctor of medicine and homeopath, 18 Thurloe Street, South Kensington, where she lived and worked from 1929 to 1980

- Dame Ida Mann, ophthalmologist, 13 Minster Road, West Hampstead, where she lived 1902 to 1934

- Innes Pearse, doctor and family health pioneer, is commemorated on the same plaque as her husband (George Williamson) at 142 Queen’s Road, Peckham, where they founded the Pioneer Health Centre in 1926.

By contrast there are around 35 blue plaques in London to medical men.

- Until September 2024, resident doctors were referred to as ‘junior doctors’ by the BMA. Articles written prior to this date reflect the terminology then in use