At the dawn of IVF

Duncan Campbell was the anaesthetist who worked with Patrick Steptoe, the pioneer of IVF. Dr Campbell's innovation – in the face of opposition – made safe laparascopic surgery possible. Now in his 90s, he tells his story

The development of IVF (in vitro fertilisation) was dependent on safe laparoscopic surgery and anaesthesia. Progress in these fields took place in Oldham, with a gynaecologist and an anaesthetist. A biologist joined them, and IVF was brought to the world.

In the early 1960s laparoscopy was regarded as an experimental research procedure with many dangers and of little benefit for clinical diagnostic purposes because of poor visibility, a danger of air embolus and a short viewing time owing to the rapid onset of patient distress from the large volume of inflated abdominal gas and also the head down tilt, both hazarding adequate pulmonary ventilation.

Many clinicians thought the risks of laparoscopy so outweighed any benefit that the procedure should be banned. This was the thinking in Australia, America and Britain at the time, so the procedure was almost non-existent in those three countries but in Europe there were several centres where laparoscopies were carried out but nowhere else in the world was it regarded as an acceptable clinical procedure.

It was with this background that in 1964 I was appointed anaesthetist in charge of the Oldham Hospitals, situated on the outskirts of Manchester. There were two main hospitals, which were district hospitals and had no links to the university or any teaching centre. All the obstetrical and gynaecology surgery was in one hospital.

This is an account of the part played by me in laparoscopy, which led up to the beginning of human IVF. The gynaecologist was Patrick Steptoe, a dynamic person with exceptional surgical skill and dexterity. He had been continually frustrated by the fact that patients who only required a quick inspection of the abdominal cavity for diagnostic purposes required a laparotomy and several days in hospital when no major surgery was required. He researched laparoscopic techniques and introduced them at Oldham, believing they would spare many patients from unnecessary major surgery.

My predecessor had reluctantly given anaesthetics for laparoscopies but they were of short duration as the patients rapidly became distressed. The other three consultant anaesthetists at the hospital were refusing to give anaesthetics for laparoscopies as they said it was too dangerous and, with the conditions which existed, they were quite right.

It is of interest that at my appointment interview, the only other candidate stated that if she was appointed, she would not allow anaesthetics to be given for laparoscopy. When I was asked the same question, I responded that it would be acceptable as long as air was not used for the pneumoperitoneum.

After discussing the various problems with Patrick and my understanding the advantages of an inspection through a small incision to avoid a large abdominal wound, we discussed what would be required to make the procedure safe as we were confident that the numerous problems which existed could be overcome.

All the changes envisaged appear as obvious safety requirements to present-day anaesthetists but at that time without the monitoring to reveal the causes of the various problems, the remedies were not obvious. Most anaesthetists thought there was nothing that could be done to make laparoscopy safe. Patrick was overjoyed at my enthusiasm and I became the only anaesthetist to work with him for the whole of my five years at Oldham.

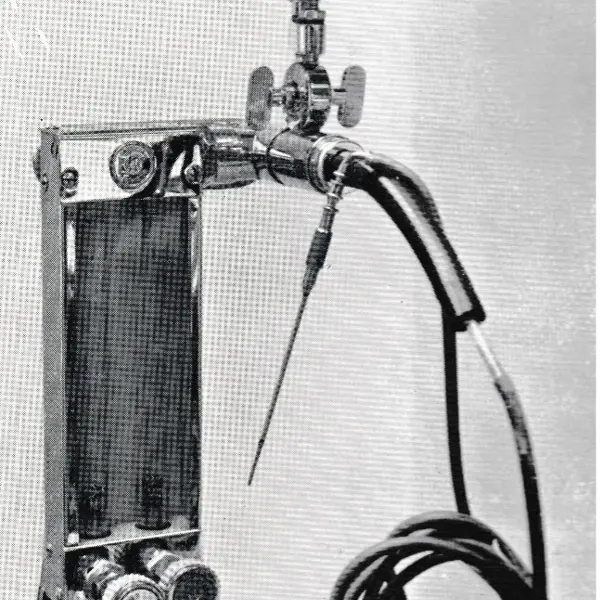

The first important item was to eliminate air as the inflating gas owing to the very real danger of air embolus. I decided that oxygen or nitrous oxide would be the best gases, and I made up an inflating system from a cannibalised Boyle anaesthetic machine, which we called the Oldham pneumoperitoneum apparatus, (pictured below) with a choice of the gas which could be used.

The gas flow was controlled through a rotameter, and a pressure gauge was incorporated to warn of excess pressure.

Carbon dioxide was not considered at this stage because diathermy was not envisaged but later it became almost exclusively used. The flow duration for the pneumoperitoneum was limited so that the flow was stopped after two litres of gas was delivered. This volume provided good viewing conditions and allowed satisfactory ventilation of the patient.

The next important item was the replacement of the respiratory anaesthetic gas delivery system to the patient as this was a major cause of patient distress. The only breathing system which existed in the hospital was the Mapleson System A, which although excellent for spontaneous respiration, and acceptable for controlled ventilation with normal pressures, was useless when higher ventilation pressures were required as in laparoscopy where the gas distension of the abdomen and head down tilt of the patient required higher than normal pressures.

With the Mapleson System A, attempts at controlled manual ventilation for laparoscopy resulted in much of the fresh gas being wasted through the expiratory valve and much of the expired gas being forced back into the patient. Spontaneous respiration was unacceptable as the head down tilt and distended abdomen resulted in grossly inadequate ventilation.

The reason for these inefficient breathing systems which existed in all British hospitals at the time was because trichlorethylene was the anaesthetic in universal use and efficient circle systems with soda lime could not be used because the trichlorethylene reacted with soda lime to form the deadly phosgene gas.

A further danger was the absence of calibrated vaporisers for any of the volatile agents. Halothane's recent availability posed an overdose risk, since its administered concentration was unknown.

Blood pressure measurements were difficult as the gauge was on the cuff and was covered by the theatre drapes. Cyanosis was difficult to detect as the theatre lights were turned down so Patrick could see into the abdomen.

Pulse oximeters had not been invented, gas analysers for oxygen and carbon dioxide were not available and ECG machines only gave a paper read-out so were useless for monitoring. Even pulse monitors were not yet commercially available. It was important to establish an anaesthetic system, which was safe with the limited monitoring available at that time.

Many clinicians thought the risk of laparoscopy so outweighed any benefit that the procedure should be banned

Duncan Campbell

The following items were ordered to make anaesthesia safe for laparoscopy:

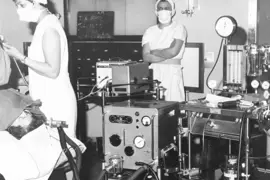

- A Barnet ventilator (pictured below) for theatre use. This would be available for all laparoscopies. No automatic ventilators existed in the theatres or anywhere in the Oldham Hospitals. The Barnett ventilator was selected as the best available for laparoscopies as it was a minute volume divider, so that by setting the fresh gas flow rate on the anaesthetic machine and the respiratory rate on the ventilator, an obligatory tidal volume would be delivered at each breath. For example, with a fresh gas flow of two litres of oxygen per minute and four litres of nitrous oxide per minute, and a respiratory rate of 12 breaths per minute, the tidal volume delivered to the patient would be 500ml. But the inspiratory to expiratory ratio could be varied as could the driving pressure, so that there was flexibility in adjusting ventilation to suit every patient. There was no rebreathing, and the set tidal volume would be delivered despite variations in abdominal pressure

- A Drager volumeter. All patients for laparoscopy were anaesthetised, paralysed, and intubated with a cuffed endotracheal tube with the cuff inflated to ensure no gas leak. The volumeter was attached on the expiratory pathway and indicated that the set tidal volume had been delivered to the patient

- Condenser humidifiers. One was connected close to the patients mouth to prevent drying out of the airway

- Accurate calibrated halothane vaporisers, to ensure no inadvertent overdose of the volatile anaesthetic could be given

- IV cannulas, so that a vein was always available for injections

- Large-scale blood pressure dials, for mounting on the anaesthetic machine so that viewing when taking blood pressures was made easier

- An ECG machine and a defibrillator for theatre use, as none previously existed.

All the ordered items arrived within a short time, and it was felt that conditions were now safe for laparoscopy.

Light source

None of these items and actions seem noteworthy today but at that time these actions seemed quite ‘over the top’ to the other anaesthetists. For instance, ventilators existed for thoracic surgery but never in general theatres.

Laparoscopies now became a safe anaesthetic procedure in Oldham and Patrick took them on with renewed vigour, but with the intense light in the abdomen there was a thermal problem which limited viewing time because of the danger of burns. Although good viewing conditions existed, even minor operative procedures could not be done because of the limited time permitted.

Soon after this in 1964, Patrick went to the first International Symposium on Laparoscopies in Europe. He arrived back very excited as a fibre-optic cold light system had just become available. He purchased one.

As well as excellent viewing he was now able to operate for prolonged periods without any patient distress or danger of burns from the light and the pneumoperitoneum gas was changed to carbon dioxide as diathermy began to be used.

One of the most frequent operations now become laparoscopic sterilisation and Patrick commented in his book published later that he was the first gynaecologist in the world to do 50 laparoscopic sterilisations. So, I was the first anaesthetist to give anaesthetics for these 50 patients, also an anaesthetic for a laparoscopic removal of an appendix, which was certainly the first in the world, but was never published as Patrick realized that he could be reprimanded for operating outside his specialty.

[Steptoe] described the conditions before my arrival as 'smash and grab raids', when it was only possible to have a quick look to try and decide if an open operation was necessary

Duncan Campbell

Patrick was able to spend time taking photographs and because pulmonary ventilation was always generous, it could be stopped without worry for the short periods of photo taking. He described the conditions before my arrival as ‘smash-and-grab raids’, when it was only possible to have a quick look to try and decide if an open operation was necessary.

Laparoscopies were being done in France, Germany, Italy and Spain but it seems all were still at the ‘smash-and-grab’ stage because of patient distress owing to the lack of specialist anaesthetists and poor understanding of the requirements to make laparoscopic anaesthetics safe.

Apart from Oldham, few laparoscopies were being done in any part of the English-speaking world, not even at any of the university hospitals as it was generally held that the poor visibility and high chance of morbidity negated any benefit. Progress at Oldham was being watched by the universities around Britain, convinced that there would be a disaster to prove them right for holding back but we never encountered any significant problems.

The hospital photographer provided Patrick with a top-of-the-range camera including flash attachment so colour slides and photographs of excellent quality could be made for presentations at international conferences.

Patrick took all the photographs himself as he knew exactly what he required to be in the field of view and it would be tedious to call the photographer every time he wanted a photo taken. Most of his operating lists now had several patients for laparoscopic procedures and he rapidly built up a comprehensive set of photos. He wrote a book on laparoscopy which included these photos. This was published in 1967.

Progress at Oldham was being watched by universities around Britain, convinced there would be a disaster to prove them right for holding back

Duncan Campbell

In 1968 there was a meeting of gynaecologists at the Royal Society of Medicine in London with an attendance of about 200 doctors. There was discussion about the diagnosis of a particular problem of the ovary.

Someone suggested laparoscopy and a very senior professor, expressing the attitude at that time, spoke at some length about how he had tried it, found it impossible to get a good view and stated that an open operation was the only course of action justifiable. Up jumped Patrick shouting ‘rubbish’ and stated he was doing many laparoscopies every week, he could get excellent views of the ovary, that he had brought some colour slides and with the permission of the chair he would be happy to show them. The showing sparked gasps of amazement and ended with applause.

As a result of this meeting, laparoscopy became an accepted procedure and for some time after this, I had enquiries about their management. In the audience at the time of Patrick’s presentation was Robert Edwards. He was not medically qualified but a biologist interested in the possibility of collecting eggs for research into IVF for childless women. Until then his only source for human eggs was at an occasional laparotomy from a cooperative gynaecologist but he was unable to develop any embryos from this unsatisfactory source. However, now laparoscopy was presenting as an ideal source. Patrick and Robert met and agreed to work together at Oldham on IVF.

Bob Edwards lived in Cambridgeshire so that it took him several hours driving to get to Oldham, but Patrick was the only gynaecologist who was willing, enthusiastic and able to offer him facilities via laparoscopy for the collection of eggs. Bob had great enthusiasm and determination and was prepared to make the journey as he was now firmly convinced IVF in humans was possible.

This was exciting research and I was happy to anaesthetise the many women who volunteered to donate eggs knowing they would not personably benefit but were willing to help for the sake of women in the future. It was interesting and stimulating to be involved with Robert, who had undertaken many years of work with IVF in animals. Robert would scrub up and assist Patrick in the theatre and unhurriedly with the laparoscope select the most suitable eggs. It is possible the GMC would have forbidden such an association if informed but presumably nobody told them.

Robert and Patrick worked together on IVF at the Oldham Hospital but they had many problems. Initially the incubator was kept in theatre and on two occasions it was turned off in the night with the death of the embryos.

The first time was thought to be a terrible mistake, so large notices were put up to forbid the turning off. The second time was obviously malicious, so the incubator was moved to a small room which they managed to obtain after some difficult negotiations. This became their small laboratory, and it was kept securely under lock and key and there were no further problems with interference.

There was great excitement at Oldham in 1969 when we first saw eggs in vitro develop to the multicellular stage and it was realized IVF in humans was possible. We all thought that an IVF baby would soon be born but it was to be many disappointing years with various problems for Robert and Patrick until eventually the first IVF baby in the world was born to Mrs Brown at Oldham on 25 July 1978.

By that time Dr Finlay Campbell had taken over the anaesthetic management of laparoscopies from me and I had taken up an appointment at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney but it was a great privilege to have been the anaesthetist of the team at the very beginning of human IVF.

Despite the absence of problems, the anaesthetic management of laparoscopy was not published by me at the time because demonstration of the safety of the anaesthetic management would need documentary evidence of CO2 and O2 levels, as well as BP, pulse rate, tidal volume and other recordings to be acceptable.

I had no recording devices, and finances were not available as the regional board thought all research should be in research centres and not in district hospitals, which should concentrate on routine work and ensure low waiting lists for surgery. Also, by the time I left Oldham, laparoscopy had become accepted as a safe procedure as anaesthetists involved now realised how to make it safe. There were by then many anaesthetists happily working in this field.

A further reason for not publishing during those first few years was that I did not want publicity as I feared senior officials might pressurise me to stop as the consensus at the time was that the dangers of the procedure outweighed any benefit.

Different times

At that time there were no ethics committees, the hospital medical staff committee was not required to sanction the activities of a consultant and the regional board had no interest, providing it cost them nothing extra and there were no complaints.

The overall view was that a consultant was the best person to decide what treatment was needed for a patient and no authorisation was required from others.

If ethics committees had existed, it is doubtful if human IVF research could have been permitted, as it involved much untried experimental work involving human volunteers with no direct benefit to them. This research was also being carried out by a non-medically qualified person, and human life forms would be created and destroyed. As it was, there was considerable local opposition to IVF research but no one at Oldham had the authority to block its progress.

It was pleasing that for his persistence and dedicated work Robert Edwards eventually received a well-deserved knighthood. Robert Edwards was also awarded the Nobel prize in physiology and the Lasker-DeBakey clinical medical research award for his work in the field of IVF. Patrick Steptoe was awarded an OBE and elected Fellow of the Royal Society.

Duncan Campbell, now 94, lives in Australia. He was the inventor of the Campbell Ventilator. In 2012, he was given the Robert Orton Medal, the highest award the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists can bestow on its fellows. Since 1978, more than 12 million babies have been born through IVF

(Main image: Laparoscopy in progress in Oldham, 1967. Barnet ventilator in the foreground. Credit: Duncan Campbell)