An act of conscience

An act of conscience

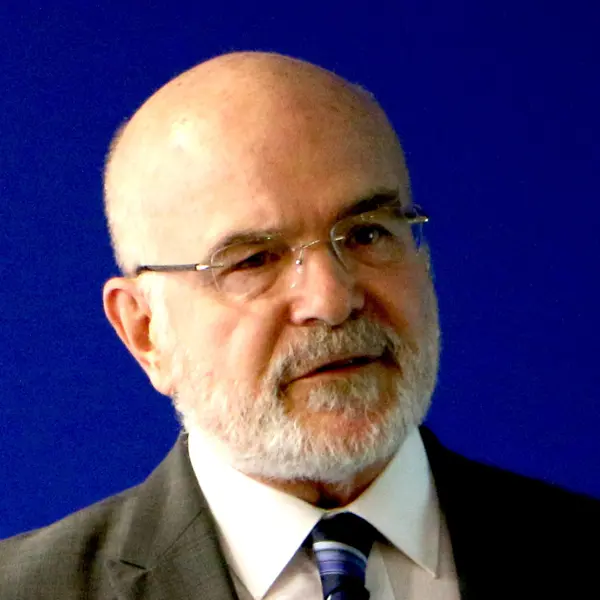

GP Patrick Hart has been to prison for actions relating to his climate activism and was recently suspended from the GMC register. He tells Ben Ireland why he has 'never been so sure' he is doing the right thing

‘I used to believe I had a future ahead of me where I was a GP partner in a small-ish practice. I wanted to set up social prescribing projects. That’s what I was doing before I started climate activism.

‘I used to believe that sort of life was ahead of me but I don’t any more because I think that would take a level of denial I’m no longer capable of.’

Bristol GP Patrick Hart, who in October became the first non-retired doctor to face suspension from the GMC register as a result of activism drawing attention to the climate crisis, is a man who believes in sticking to your morals.

He does not see the future he had envisioned for himself any time soon because, although his suspension is for 10 months, he expects it will be extended indefinitely, as long as he refuses to apologise for his actions.

His actions, which he has undertaken in a bid to raise the alarm about the climate crisis and considers an act of conscience, led to time in jail – and the loss of his career as a doctor.

No apologies

The implication from the recent MPTS (Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service) tribunal was that, if he just apologised, admitted his actions were wrong, that a suspension would be unnecessary.

But Dr Hart believes strongly that his actions were done for the right reasons. He will not say sorry, abandoning his moral integrity, if he does not truly believe it.

As he put it in an interview with The Doctor: ‘There’s this idea that you’re supposed to show remorse, take it all back and plead for mercy, bending your will to authority.

‘It seems odd to reward that sort of behaviour. My commitment is to the truth, and the truth is I thought about all of this for years before I did any of it.

‘I have never before been so sure about something, and I’m not prepared to lie to get a lenient sanction. If I do, my dignity is gone.’

I'm not prepared to lie to get a lenient sanction. If I do, my dignity is gone

Patrick Hart

He says this as someone with more to lose than the other climate activist doctors who have faced suspensions owing to climate activism. While they spent time behind bars, neither Sarah Benn nor Diana Warner faced the loss of their careers because they had already retired. No clinical concerns have ever been raised about any of the three GPs.

‘Temperatures have been off the charts,’ Dr Hart says. ‘We’ve already lost the 1.5ºC safety limit [agreed in the 2015 Paris climate agreement] and realistically we’re heading towards a 2ºC-plus world, an out-of-control positive feedback loop and tipping-point climate-collapse hothouse Earth.’

With that prediction in mind, based on scientific evidence, Dr Hart doesn’t feel he should apologise for his activism, even if it would make it more likely for his suspension to be lifted on review.

October’s tribunal found Dr Hart’s fitness to practise to be ‘impaired’ by reason of misconduct and convictions. The panel concluded that a finding of impairment was ‘necessary to protect the public, to uphold proper professional standards, and to maintain confidence in the profession’.

The MPTS tribunal followed Dr Hart’s sentencing to 12 months in jail in January for criminal damage to petrol pumps at an Esso garage on the M25 in Thurrock, Essex, after breaking off from a Just Stop Oil protest which had blocked vehicles accessing the forecourt in August 2022.

The tribunal noted that Dr Hart ‘had a history of offending’. He has three convictions and three acquittals relating to activism drawing attention to the climate emergency – including throwing orange powder on the pitch during an England Rugby match at Twickenham, for which he was cleared.

Dr Hart’s convictions include one for aggravated trespass on land which was being used for storage and transportation of fuel, which he intended to obstruct or disrupt, and led to a £500 fine in November 2022. He also climbed on to pipework to disrupt operations at the Exolum Pumping Station, Grays, in April 2022, for which he was on bail during the Esso garage incident.

Dr Hart was charged with and tried for a criminal damage offence, relating to an incident at the Canary Wharf office of the bankers JP Morgan in July 2022, but the jury could not agree on a verdict and thus there will be a re-trial next year.

Dr Hart self-referred to the GMC in September 2022 when legal proceedings were taken against him.

He admitted all the convictions brought as evidence in the tribunal but argued that, through taking part in peaceful activism, he did not warrant being suspended from the medical register, preventing him from practising as a doctor.

Scientific basis

Dr Hart told the hearing that the evidence behind the climate emergency is ‘accepted scientific fact’.

The MPTS finding said Dr Hart ‘expressed uncertainty about the level of climate literacy among tribunal members’ and ‘emphasised that a good grasp of the scientific facts was, in his opinion, essential to making a reasonable judgement about his conduct’.

He compared this expectation on an evidence base to that which would apply if the case concerned clinical practice, where a tribunal would be expected to have a working knowledge of the relevant medical issues.

And he argued that traditional legal and regulatory frameworks misunderstood acts of conscience such as his, since processes are designed for offences motivated by self-interest whereas his actions were intended for the greater good, and risk assessed.

Dr Hart said that, as a doctor, he felt compelled to act to protect life, comparing his actions to historic examples of doctors breaking laws for social justice, such as suffragists and 19th century reformers. He argued that similar civil disobedience was necessary given the urgency of the climate crisis.

Legal backing

Dr Hart was allowed to submit new evidence, in the form of a legal opinion by the lawyer-led campaign group Lawyers Are Responsible.

This opinion states the effect of climate change is of ‘particular concern’ to medical professionals owing to ‘the unique and trusted role which doctors play in society’.

It notes that the threat caused by climate change ‘increasingly features’ in medical journals and human rights courts and should be taken into account when interpreting the GMC’s ‘overarching objective’ of the ‘protection of the public’.

The opinion, by Tom Cross KC and Lucy Jones, concludes that a doctor’s ‘fitness to practise should not be regarded as impaired, whether by reason of misconduct or otherwise’, if taking part in activism relating to the climate crisis.

It says that, while some climate activism may lead to criminal convictions, ‘it does not follow that a doctor’s fitness to practise is impaired by reason of such a conviction’.

The handling of Dr Hart’s case has drawn criticism from the United Nations special rapporteur for environmental defenders, Michel Forst, who visited him in prison. He has called for the termination of fitness-to-practise proceedings against him and described his treatment as a ‘double punishment’.

Mr Forst submitted video evidence to the tribunal, through which he urged the panel to judge Dr Hart’s actions in their full context.

Wouldn’t you think that being in a prison cell for months is a severe enough punishment for having caused limited criminal damage to an oil multi-national?

Michel Forst, UN special rapporteur for environmental defenders

He said that, under the Aarhus Convention, the UK has ‘a legally binding obligation to ensure that members of the public, as environmental defenders, are not penalised, persecuted or harassed for their involvement in the protection of the environment by any state, body or institution… and this includes the General Medical Council’.

He added: ‘Dr Hart is an environmental defender who has faced such persecution by the UK courts and today faces a risk of further persecution on his professional life.’

He said that those who cause damage to property can be held accountable, but said any sanction must be ‘reasonable, proportional and serve a legitimate public purpose’.

‘In the present case, Dr Hart has already been held responsible for his law-breaking. Wouldn’t you think that being in a prison cell for months is a severe enough punishment for having caused limited criminal damage to an oil multi-national that makes billions of revenue from a business activity that involves massive carbon emissions that contribute to climate change?

‘When you decide to remove, or further suspend, his medical licence please do keep in mind that Dr Hart has already been sanctioned, and harshly so. Removing his medical licence would amount to punishing him again for the same action. I cannot see how, from a social or moral perspective, this could be justified or meet the obligations under the Aarhus convention.

‘Dr Hart is a doctor who inspires trust in the medical profession, not the opposite.’

Arguing against his suspension, Dr Hart told the tribunal: ‘In times of great crisis and injustice, it is always right to speak truth to power, even when that has consequences.’

He said that by ignoring the context of his actions, the panel was choosing to ‘look the other way’.

Dr Hart argued that it was ‘quite conceivable’ that as many members of the public gained confidence in him than lost it. ‘The climate crisis is a health crisis,’ he said. ‘So who better to give that message than a doctor?’

And he called the tribunal ‘frightfully hypocritical’ in that it said that he ‘did not accept’ that his actions were ‘morally wrong’ when it had also said it was not taking into account his motivations, only his actions.

He said: ‘You are clinging desperately to a rule book that is no longer fit for purpose... you fail to recognise that we are at a juncture in history where the rule book must be torn up and rewritten.’

Dr Hart’s assessment now is that the tribunal was conducted to ‘demonstrate there has been a process’, not to make an evidence-based decision.

'Risk of repetition'

The GMC submitted that Dr Hart failed to act within the law, failed to justify his patients’ trust in him or the profession and that his actions were in breach of the GMC’s Good Medical Practice guidelines.

The regulator said his prison sentence indicates the seriousness of Dr Hart’s conduct, and that continued criminal conduct while on bail ‘undermines public confidence in the medical profession’. Ceri Widdett, speaking for the GMC, said damaging petrol pumps involved the ‘use of violence’.

She added that Dr Hart’s misconduct and conviction were ‘remediable’, but ‘have not been remedied’ as he ‘had not developed insight’ and therefore a ‘risk of repetition existed’.

She argued that public confidence in the profession and its system of regulation would be ‘undermined’ if Dr Hart was not found to be impaired.

Dr Hart submitted that imprisonment, while a marker of seriousness, can be used as a ‘deterrent to legitimate protest’.

He said his actions did not cross the line into violence because they targeted property, not people, and he has otherwise always been a law-abiding citizen.

The climate crisis is a health crisis, so who better to give that message than a doctor?

Patrick Hart

He told the hearing he did not consider himself above the law and noted how the UK Government had repeatedly broken laws it had itself passed, most pertinently the Climate Change Act 2008 and laws about air pollution. He said fossil-fuel companies regularly flout the law and are not held accountable for the damage and public health implications of their actions.

Dr Hart submitted that his actions, damaging ‘some small squares of plastic’, paled in comparison to ‘the permanent irreversible collapse of your economy and civilisation’.

The tribunal said it made its impairment decision with a focus on the nature and seriousness of Dr Hart’s acts, rather than his beliefs and motivation.

It found that his actions, in deliberately breaching a High Court injunction, constituted misconduct and that he used his status as a doctor to ‘maximise the impact’.

While noting his actions did not take place in the course of professional practice, the tribunal said there was a ‘clear, unwarranted risk of harm’ to the public, protestors and emergency services.

His intention to draw attention to the action ‘further reinforced the seriousness of the misconduct’, the tribunal noted, adding that his motivation – to draw attention to climate change – was ‘not a relevant factor’.

The tribunal determined that Dr Hart’s conduct constituted serious misconduct, and that both this misconduct, and his convictions, each amounted to his impairment and also brought the profession into disrepute.

The tribunal said it ‘was of the view that public confidence would be undermined if Dr Hart was permitted to practise unrestricted, given … the serious nature of his misconduct and conviction’.

Dr Hart said he had no further plans to take part in direct action as he felt that the opportunity to limit climate change to 1.5ºC had ‘already been missed’. He argued that his actions were consistent with his professional values of honesty, responsibility and protection of life in what he described as ‘seriously not normal times’.

In prison

While in prison, Dr Hart kept himself to himself – spending much of his time reading.

‘I never thought prison was a place I was going to see,’ he told The Doctor. ‘In a way it felt surreal, and in a way it felt interesting to experience something I thought I would never experience. I didn’t resent it as much as I thought I would.

The sentence was ‘no great shock’, coming months after being found guilty, but Dr Hart still felt ‘numb’ when the judge handed it down.

He cried on the way to the train station when travelling from Bristol to Chelmsford Crown Court: ‘I don’t think it was self-pity, just an emotional release from the tension I’d been carrying for a long time,’ he said. ‘It was a catharsis. I felt quite peaceful. A sort of grief for the world.’

While in prison, he ‘didn’t feel continually on edge’, but recalled ‘an increased awareness of my physical presence and what was around me, in the way you might if you’re walking home on a dark night’. It felt ‘a bit like the school playground’.

Danger was, however, always a possibility. He was assaulted by one of his cellmates – who he described as ‘a really troubled man’ who ‘had come from the most unspeakably traumatic background’ and had a ‘chaotic life’ involving addiction to hard drugs.

‘Fairly early on, I realised this man would probably end up assaulting me,’ said Dr Hart. ‘We were locked in for a whole weekend, because they were short-staffed. He was frustrated, got more and more angry and was verbally abusing me. I lost my discipline and snapped back at him [verbally], after really trying to be calm. So he punched me. I said I wasn’t going to fight him, and he punched me again. I just sat there looking him in the eyes and he stopped. After that I asked for a change of cell.’

During his four-month stint inside, Dr Hart also shared cells with ‘a horrible, controlling, misogynistic pig’ imprisoned for assault, and a ‘racist, sexist, homophobe – who was actually quite nice to me because I’m a white man’.

Fairly early on, I realised this [fellow prisoner] would probably end up assaulting me

Patrick Hart

During his sentence, Dr Hart faced an interim orders tribunal, resulting in an interim suspension. The time he was suspended prior to the MPTS tribunal did not count towards the suspension he was given last month.

Dr Hart told The Doctor he was surprised by the reasons given for the interim suspension while in prison, which included a suggestion from the GMC that he may come under pressure to use his practising privileges while in custody.

‘Their initial assessment was that it would protect me from feeling the pressure from other inmates,’ he said. ‘I told a few other prisoners that and they thought it was hilarious. The other reason was to protect other prisoners from me, as if I was somehow going to decide to prescribe them all pregabalin – perhaps for my own benefit, for bribes, vapes or prison cred[ibility]. It all felt very Emperor’s New Clothes.’

The third reason was that the public would expect a doctor serving a prison sentence to be suspended, which Dr Hart said he asked if there was a precedent for and received no response.

Meanwhile, in Bristol, many of his patients and supporters attended a vigil calling for his release, support for which he is ‘very grateful’. When Dr Hart was released, his interim suspension was renewed on the basis the public would expect it.

‘The GMC presented this as if it was self-evident,’ he said. ‘I didn’t think it was. For an organisation representing an evidence-based profession, they didn’t seem too interested in the evidence.’

After his release, he spent about another month on licence, with an electronic tag, and had to inform probation if he wanted to leave the Bristol area, even just to visit his parents.

Without being able to work as a doctor, Dr Hart has thrown himself into volunteering at farms, learning roofing and insulation skills as well as undertaking the concept of 'deep adaptation' – preparing for a world of climate breakdown by taking constructive action to try and prevent mass death and disruption where possible.

He said: ‘If we don’t have people returning to the land to try and adapt to the really harsh weather conditions ahead of us, then we’re going to starve.

‘I hope it doesn’t happen, in which case I’m just wasting my time doing a load of gardening. Maybe there is an amazing breakthrough that solves all our problems but I’m going to hedge my bets and prepare for the worst.

‘If the breakthrough doesn’t happen, can I at least make the changes in my life that – if we all made them – would prevent humanity from f**king everything up for the next 10 million years? I want to see if that’s possible.’

Back to the land

Since release from prison, he has not been involved in any activism. If he attended any protests at all, even those completely within the law, a condition of his release says he would be ordered back to prison immediately. This, he said, makes him feel ‘paralysed’, as he did about the climate crisis before taking part in activism.

His finances have ‘not been great’, but Dr Hart said having lived a relatively low-impact life on a GP’s salary left him with some savings he’s been living off, and it helps getting vegetables from the farms he volunteers at.

Now the tribunal has concluded, he plans to re-enter the world of paid work. He says he ‘can’t afford to be choosy’ about what he does: ‘I’d rather work in medicine because it’s meaningful and satisfying. But there is dignity in work, whatever it is.’

Dr Hart fears he may struggle to find employment in medicine in the future, even if his suspension is lifted on review.

‘I imagine some practices might have reservations about employing me, so I wouldn’t expect to walk back into a job,’ he says.

‘The last five or six years of working and doing activism were exhausting, and I cut out an awful lot from the rest of my life so that I could do both [medicine and activism]. But I did both because I thought it would be important that when one day [if he was brought before a tribunal] I could say, “I’ve been working this whole time, contributing to keeping the NHS limping along, right up until I went to prison”.

‘I’ve striven to do that the whole way through. I felt quite strongly that I needed to show I was still committed to working as a doctor. I never checked out of this career.’

'Ethical duty'

At this year’s annual representative meeting, BMA members voted to recognise that climate change is a public health emergency and that medical professionals have an ethical duty to advocate for urgent action.

Punitive action against doctors who take part in non-violent climate activism was condemned with the question posed: ‘If we punish the doctors who shout for help, who is left to resuscitate society?’

Speaking in a video call from his home, which he is renovating himself to create as self-sufficient a life as he can, Dr Hart’s commitment to his morals runs through all of his answers.

He knew he would have had a better chance of returning to medicine if he ‘told them what they want to hear’ – that he is sorry for his actions and will never do it again – but he has been suspended and the NHS is down one otherwise unblemished GP as a result.

Reflecting on it all, he says: ‘Life’s hard, and we don’t always get it right. But one day I’m going to die and – looking back on my life – I don’t want to have too many regrets about what I should or could have done.

‘Life is a constant learning curve, it’s about trying to do a little bit better and make it count when you can. Even when the thing that would be most beneficial would be to sell out.’