Volunteering for Orbis: a mutual benefit

Volunteering for Orbis: a mutual benefit

Offering to help a flying eye hospital allows a doctor to improve facilities in developing countries while also sharing life-saving knowledge

I was born and grew up in Nigeria, which may have made me more aware of disparities in healthcare around the world. I’ve previously volunteered for Médecins Sans Frontières, in crisis zones. But I’ve always had a great interest in teaching, and that is what led me to volunteer for Orbis, as an organisation which focuses more on training.

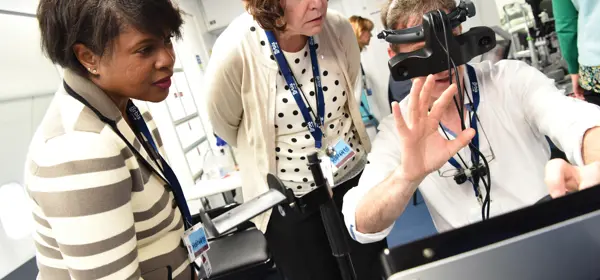

I have been an Orbis volunteer since 2005. The previous year, I had been invited to come aboard the Orbis Flying Eye Hospital (pictured above), an accredited ophthalmic teaching facility on an aircraft, when it was visiting Stansted Airport on a goodwill tour – and I liked what I saw!

The reason I’m still here is because Orbis recognises it is not enough to just train the surgeons. Rather, excellent patient care relies on a good nursing, scrub and theatre team, among other things. A hospital needs good anaesthesia and recovery, equipment that works and appropriate sterilisation.

I’ve now been on 20 programmes with Orbis to countries including Ethiopia, Bangladesh and Nepal. My first assignment was to Varna, Bulgaria in 2005 and I was one of the first UK volunteers to work with the new aircraft on its first programme, which took place in Shenyang, China, in 2016. My most recent programme was in Zambia in 2023.

One of the most rewarding things about volunteering with Orbis is working with anaesthetists in low- and middle-income countries. Anaesthesia is sometimes less prioritised, which is evident in the mortality rates. In the UK, the mortality rate from anaesthesia alone is about one in 100,000, but in some Sub-Saharan African countries, it’s just below one in a thousand. This can be a result of less overall support, training and equipment. I therefore like to work with healthcare teams in local hospitals to strengthen anaesthesia services and petition for its importance to ensure patient safety.

There are certainly challenges when it comes to volunteering for Orbis. The toughest thing is if we can't proceed with a surgery. The first day of an Orbis programme is a screening day. If a patient is very sick, administering anaesthesia can be risky, so we may have to postpone their procedure.

However, one of our main aims is to train local surgeons to perform these procedures on their own, so the patient can be treated once they’re better. It's rewarding to hear the patient has had successful treatment thanks to our support. It is also important to show local anaesthetists when to push back surgeries if it is unsafe to perform them. This stresses the shared responsibility of surgery and anaesthesia, promoting teamwork and thorough screening.

The Flying Eye Hospital is very well equipped, but, as you would expect, there are significant differences between the drugs and equipment one finds in the UK compared with the low- and middle-income countries where Orbis works.

For example, some of the countries we work in still use the general anaesthetic halothane, which the NHS stopped using in 1990s. Nevertheless, I’m fortunate to have trained when halothane was still in use and patient monitoring included manual methods such as someone checking the pulse and another measuring the blood pressure. Being familiar with old and new techniques allows me to work in theatres all over the world but also train anaesthetists to use new equipment.

With Orbis, there is a very strong sense of us acting collaboratively with local hospitals, so we can work together to establish their equipment and training needs. One of the most rewarding parts of volunteering is returning to a country and seeing the improvements over time. I’ve been to Ghana three times, and it is encouraging to see the progress which has been made, reassuring me that our work is making a tangible difference.

We can keep in touch with trainees, directly through email, and, for example through the free anaesthesia curriculum on Orbis’s telemedicine platform, Cybersight, which I helped to write.

The benefits of volunteering really are mutual.

Best of all, of course, we can help to prevent avoidable blindness around the world. Orbis can help enhance services, improve safety and reduce errors. We can support doctors who may not have had our opportunities but face greater challenges and often care for much sicker patients. We can raise awareness of eye conditions in the countries we visit – it’s not unusual for health ministry officials and the media to pay us a visit.

And in return, volunteering enhances my resilience, teamworking, problem-solving and bolsters my clinical skills. As a colleague once said, I come back from an Orbis programme more ready to cope with the challenges the NHS throws at me. We could certainly all benefit from that.

Ian Fleming is a consultant anaesthetist at King’s College Hospital in London